We climbed Tibidabo to get to Sagrat Cor the slow way—a metro to the edge of Barcelona, then a bus that corkscrewed up the hillside while the city fell away and the air felt like somebody was turning down the oxygen. The church appears long before you arrive, a stone crown perched on the city’s highest peak, visible from nearly everywhere below. Up close, it looms—part fortress, part wedding cake—standing guard over an amusement park that’s somehow even older. The only thing competing with the view was the smell of waffles and sugar.

Barcelona’s choice for its holy mountain is ironic. The mountain’s name, Tibidabo, comes from the Devil's offer to Jesus in the desert, “…(T)ibi dabo hanc omnem potestatem et gloriam eorum.” (“I will give you all this authority and their glory”) as they looked down from an exceedingly high mountain upon all the kingdoms of the world, and the glory of them. From up here, it’s easy to see why the name stuck. The city sprawls below like divine geometry—the Eixample grid stretching cleanly to the sea, the Sagrada Família spearing the skyline to the left, and Montjuïc rising to the right. It's the view of a lifetime, as long as you don't think too hard about who offered it first. (Satan. I’m talking about Satan.)

Sagrat Cor itself exists because 19th-century rumor met 19th-century Catholic resolve. Word spread that someone planned to build a Protestant church and a casino on this very summit—two affronts to decency rolled into one. A group of Catholic knights promptly bought the land before the dice could roll. Enter Don Bosco, the Italian priest and founder of the Salesians—a teaching order devoted to the moral education of working-class youth—who visited Barcelona in 1886 at the invitation of local patron Dorotea de Chopitea. Between her money and his moral authority, their piety averted the panic, and they laid the groundwork for what would become Barcelona’s own Montmartre—a hilltop basilica dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Nothing motivates devotion quite like the specter of a rival faith and a roulette wheel.

As massive as it is on the outside, the church seems oddly small inside—like a Spanish anti-TARDIS. Maybe the builders wanted to reserve the drama for the skyline. Architecturally, it’s two buildings stacked atop one another—a Romanesque-leaning crypt below and a more vertical, Gothic-inflected basilica above, crowned by a bronze Christ throwing his arms wide over the city.

Enric Sagnier—the busiest Barcelona architect you’ve never heard of—drew it up, and his son carried it over the finish line decades later. Sagnier wasn’t a showman. He was more into orderly, muscular masonry and medieval flourishes without the Gaudí curveball. If Gaudí was the city’s virtuoso soloist, Sagnier was the first chair who kept the orchestra in tempo. From below, it looks more like a stone fortress that was repurposed as a church at the last minute. With Super Jesus as the topper.

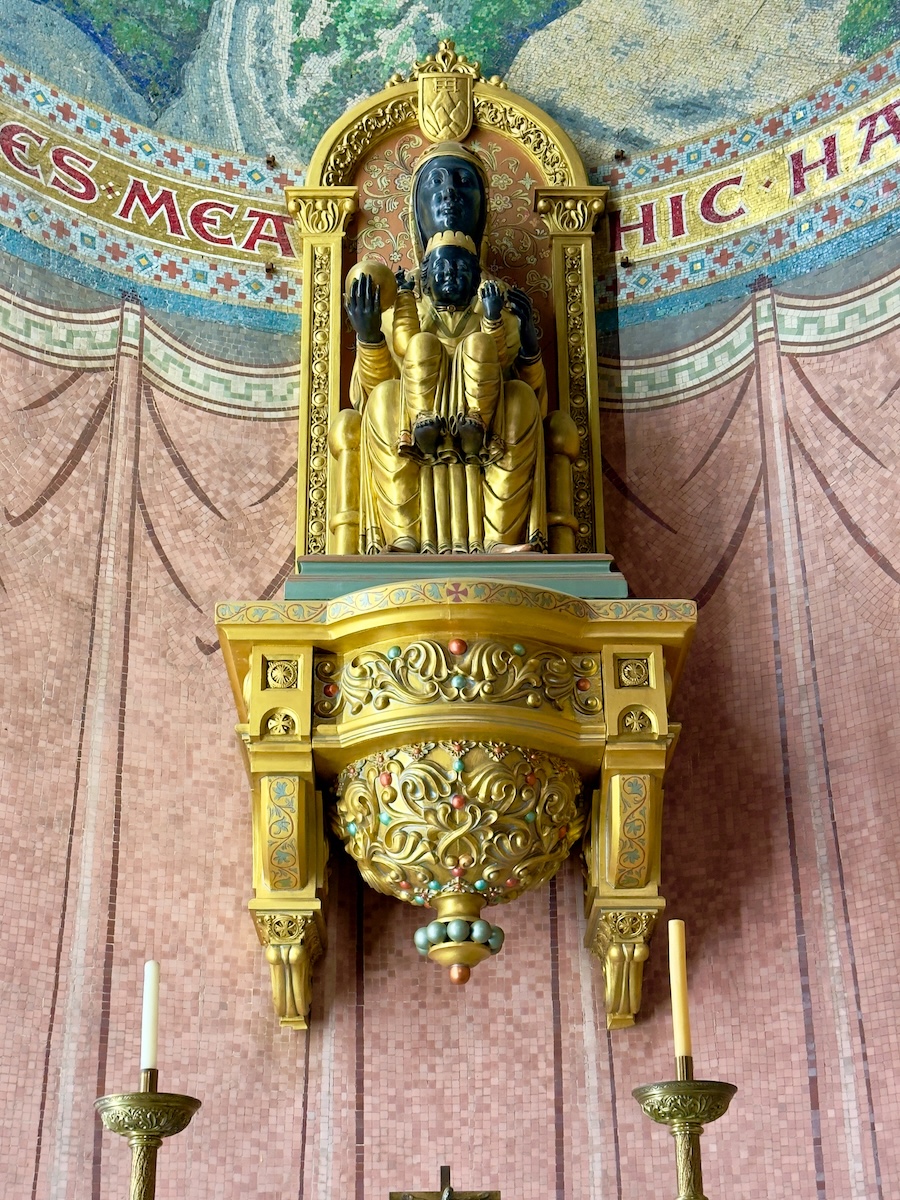

Like most everything in Barcelona, the church was built for the long game. First came a small chapel in 1886 to plant the flag. The crypt followed in the early 1900s, mosaicked and sculpted with unmistakable modernist fingerprints. The big church above wasn’t wrapped up until 1961. Rome granted it “minor basilica” status that same year, Catholic for “this one counts.”

Inside, the light filters through filigree glass onto a surprisingly intimate nave. The big surprise, though, is the small modernist chapel designed by Joan Busquets, rescued and reassembled here decades after it first dazzled on Passeig de Gràcia. And then there’s the organ—2,000-plus pipes’ worth of neo-Baroque thunder.

That next-door situation is half the reason Tibidabo feels so strange and so right. The amusement park isn’t an afterthought—it was built in 1901—it's coequal. Families drift between pews and cotton candy, couples pose under the Sacred Heart, and then queue for a spin with the best view in Catalonia. It’s less clash than truce—Barcelona recognizing that joy, ritual, and spectacle are all part of the same civic toolkit. If God and Disney ever shared a lease, the terms would look like this.

The hill collects other architectural outliers like a magnet. A short hop away sits Bellesguard, Gaudí’s angular castle-house, all stakes and story—part medieval homage, part early experiment in the geometry he’d later bend into those famous curves. On another ridge, Norman Foster’s Collserola Tower spears the sky—a 1992 time capsule from Barcelona’s Olympic glow-up. In one swivel of the head, you jump centuries.

We broke our own symmetry by descending in style, taking the funicular down. It's a tidy metaphor for Tibidabo—a practical machine that also delivers drama, easing you from panoramic serenity to normal city life in a single glide. Halfway down, the church and the Ferris wheel line up for one last improbable frame, the kind of image that squeezes decades of civic contradictions into a postcard—sacred and secular, earnest and theatrical, ancient impulse and modern habit.

If you come up here looking for a tidy moral, you’ll be disappointed. Tibidabo is less about answers than about coexistence. A century ago, a rumor about a casino triggered a cathedral. Today, the cathedral and the rides make an honest pairing. The summit still whispers the old line—All this I will give you—but in Barcelona, the promise isn't power so much as perspective. Everything the Devil supposedly offered is spread out below—the port, the grid, the towers, the parks, the thousand small lives happening at once. The city is yours, for a minute, if only to look at.

And that’s enough. The mountain can hold a church and a roller coaster. The skyline can hold saints and scaffolds. Barcelona doesn’t pick sides—it just keeps building the view.

Write a comment