Most people start their Antoni Gaudí pilgrimage with the Sagrada Família or the swirling rooflines of La Pedrera. I mean, we did. But there’s more to see, like Casa Vicens, which is something of an architectural deep cut. The home today is hidden in a narrow Gràcia street, wedged between apartment blocks, looking too small to be a World Heritage site. It doesn't have the size or swagger of Gaudí's later work. But this is where it all began—his first independent commission, his first house, and his first real chance to test what he believed architecture could be.

Gaudí was fresh out of architecture school in 1878, decades away from the fame that would turn his buildings into pilgrimage sites. His patron, Manuel Vicens i Montaner, was a brick and tile manufacturer who’d inherited a modest lot at what was then the trailing edge of Barcelona. He wanted to build a summer house. Gaudí wanted to build the universe. And this is what appeared between those two ambitions.

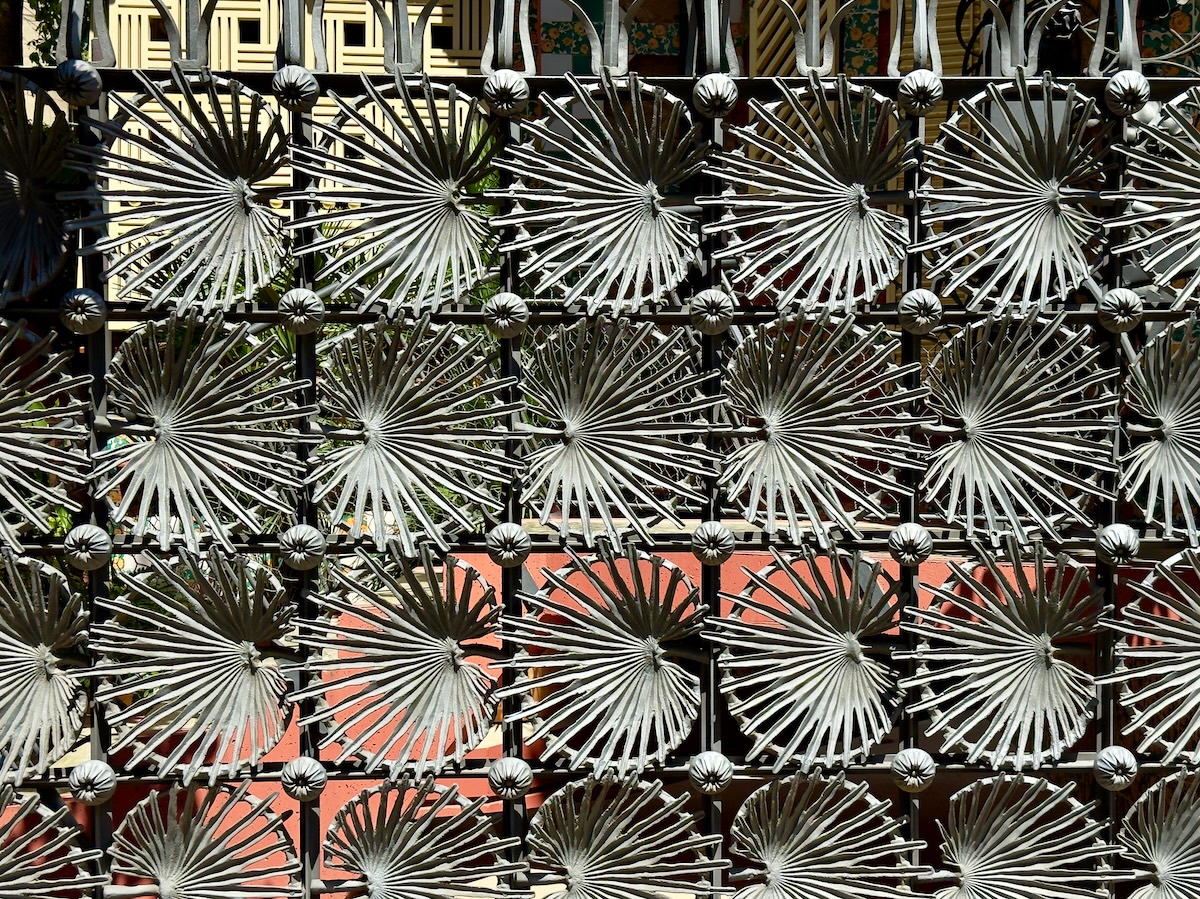

He was still young, but already obsessed with nature and function—ideas that would later be mythologized by 20th-century critics and the Church. He didn’t need much prompting because he apparently found inspiration on the site itself. “When I went to take the measurements of the plot,” he said, “it was completely covered in small yellow flowers.” Those marigolds became the recurring motif for the ceramic tiles he used to wrap the façade. He also found palmetto palms on the property and incorporated the fan-shaped leaves into the iron grille design. The whole house, he said, grew out of what he saw that day on the ground.

That façade still startles. Color everywhere. In an era when most Barcelona homes were clad in stone or stucco, Gaudí used ceramic on the exterior—unheard of at the time—and tiled it like mosaic marigolds caught mid-bloom. He combined Moorish geometry with Japanese carpentry, incorporated Catalan verses into the walls like Arabic inscriptions, and oriented the entire house southwest to keep it cool in the summer. The result was half Moorish villa, half nature experiment. From the street, it looks like it's trying very hard not to outshine its neighbors—and failing completely.

Once you’re inside, you realize how tightly the garden and the house intertwine. Every wall, ceiling, and fireplace works at some level to bring the outside in. Painted ivy climbs from the dining room up through the beams, ceramic carnations bloom across cornices, and birds flit through painted friezes. Gaudí designed every piece of furniture to match—an early exercise in total design, long before that idea existed. Decades of smoke and varnish dulled these surfaces and decorative elements, leading people to believe Gaudí had chosen a subdued palette appropriate to Victorian homes of the time. But when restorers cleaned the rooms during the 2014–2017 conservation effort, the original colors reappeared—bright and unexpected, more tropical than ecclesiastical.

Seeing those colors in their original glory makes you realize how much Gaudí was already playing with light, color, and natural systems, long before anyone thought of him as an eco-architect. On one covered porch, he even built a fountain whose iron lattice scattered sunlit rainbows across the sitting area. The fountain water was rain collected on the roof and stored in cisterns hidden among the ornamentation—a practical cooling system disguised as decoration.

Over on the terrace, the railing doubles as a bench, another Gaudí original he’d reuse at El Capricho and La Pedrera. From here, the Vicens family once looked out over their extensive gardens, not the apartment blocks we see today. There was once a brick waterfall designed to cool the air—a summer-house luxury that sadly no longer survives, but hints at how seriously he took climate and comfort. It’s hard not to picture Dolors Giralt, the lady of the house, reading in the domed room nearby while the breeze moved through the latticed balcony. Gaudí even painted a tower from the rooftop on the ceiling, as if the sky itself had peeked inside.

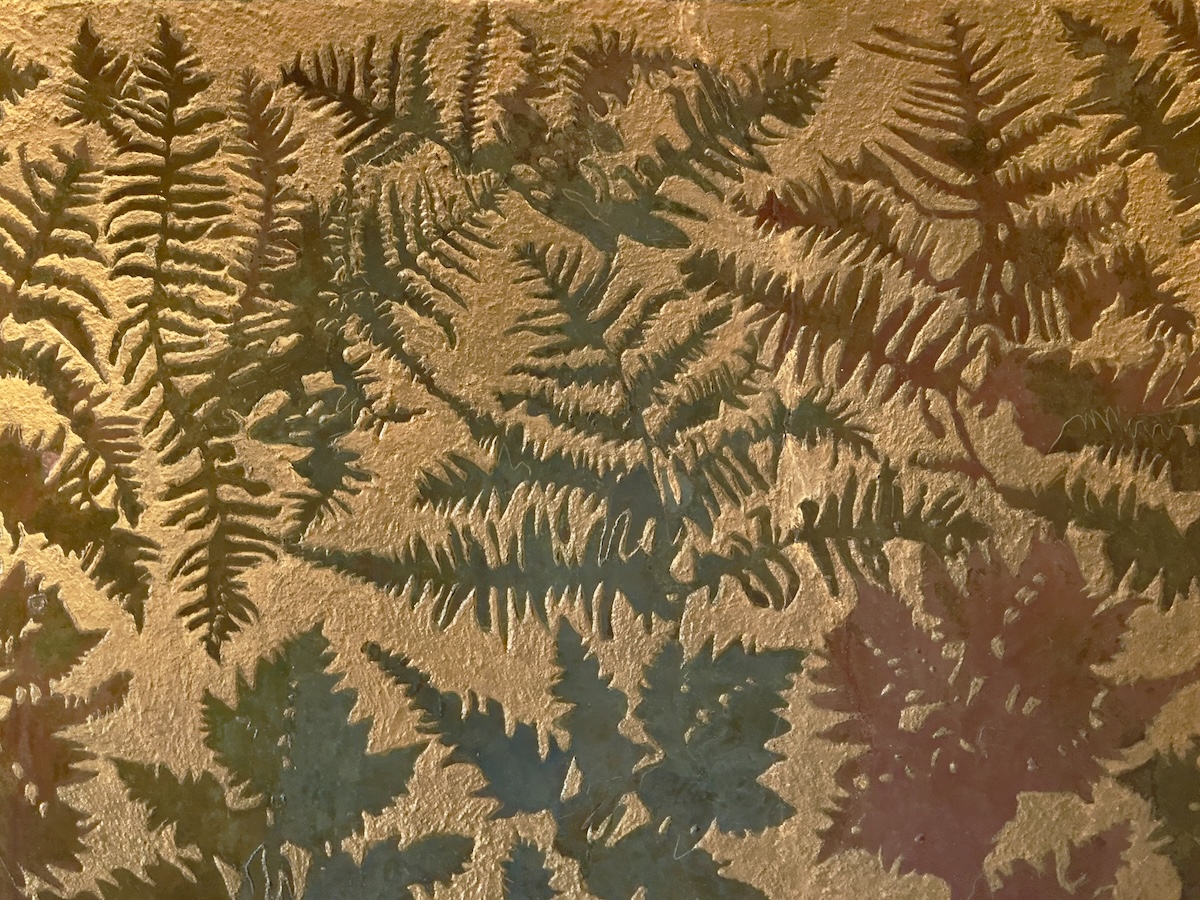

The smoking room on the main floor—one of the few spaces that was clearly gendered back in the day—was an Orientalist fantasy of deep blues, papier-mâché muqarnas on the vaulted ceiling, and gold-painted leaf patterns. It must have smelled like a club at midnight. Gaudí would revisit this idea in the grander smoking room of Palau Güell a few years later, but this was his first—a nod to the Arabic and Persian architecture he’d studied obsessively.

The family’s living area on the second floor is less grand than the main floor, but more revealing of how Gaudí imagined people living inside his designs. The daughter’s bedroom is painted entirely in pink—walls, floor, and ceiling—because Gaudí couldn’t stand a break in the chromatic logic. He shaped the hall into hexagons to save space and encourage fluid movement. Even the bathrooms, rare luxuries in 1880s Barcelona, were ahead of their time, split into three parts (a bath, a dressing room, and a lavatory) for comfort and privacy —a layout that Barcelona homes wouldn't adopt for decades. And everywhere, the same botanical motifs climb, crawl, and connect.

On the roof, you can recognize the prototype for every later Gaudí rooftop you’ve ever seen. Walkable paths. Chimneys turned into sculptures. Hidden systems to collect and channel water. Even a small, tiled tower with a built-in bench for catching breezes—his first attempt to make a rooftop truly livable. A surface that works and astonishes at the same time. He’d go on to perfect it at Casa Batlló and La Pedrera, but this was his first experiment—half laboratory, half lookout.

Casa Vicens was finished in 1885, years before the word “Modernisme” became fashionable. It was a manifesto disguised as a house. Every future Gaudí trademark appears here in miniature—his fascination with nature, his obsession with geometry, his flair for theatrical façades, his practicality hiding under ornament.

When you leave through the garden—now surrounded by cafés and apartment balconies—it’s easy to forget this was once a summer retreat in the wide-open countryside. Today, it feels almost shy, a little trapped between larger, louder buildings. But the energy inside still hums. You can see how Gaudí, barely 30, was already designing a world in which architecture, nature, and imagination refused to stay in their lanes. You can see how Gaudí, barely 30, was already designing a world in which architecture, nature, and imagination refused to stay in their lanes. Not bad for a house inspired by a handful of marigolds and a palm leaf.

Write a comment