The Uber dropped me at the gates of the Cementiri de Montjuïc, and the driver watched me for a little while before leaving to be sure I hadn’t made a mistake. It was a perfect Barcelona morning—bright, warm, the air smelling faintly of pine and sea—but maybe a little too nice for spending the day among the dead.

Montjuïc, “Jewish Hill,” was named for the medieval Jewish cemetery that once covered part of this slope. The Jews themselves lived inside the city walls, in El Call, the walled quarter off Plaça Sant Jaume, until 1391, when mobs wiped it out and the survivors were killed, converted, or expelled. The hillside cemetery was abandoned for centuries, until the city decided to move Christian burials outside the walls for health and hygiene reasons. And of course it came right back here. Call it historical recycling.

You see the cemetery long before you reach it—tier after tier of marble and masonry stacked up the mountainside like bleachers, ready for the apocalypse. Poble Nou, the older cemetery near the beach, had filled up by the late 1800s, and Barcelona’s booming bourgeoisie needed a new resting place—ideally with better views. The textile barons who were busy hiring starchitects like Gaudí, Domènech i Montaner, and Puig i Cadafalch to design their apartment blocks on Passeig de Gràcia kept them on retainer for their death houses too. The result opened in 1883—150,000 tombs climbing the hill like a wedding cake of Modernisme, Gothic Revival, and shameless personal pride. If Poble Nou was an orderly filing cabinet for souls, Montjuïc was an open-air art museum with death as the admission fee.

The scale alone is absurd. From the gate at Mare de Déu del Port, the road snakes upward through switchbacks and stairways, every landing offering another angel frozen mid-swoon—one shielding her eyes, another clutching her heart like she just remembered the rent was due. Their marble wings catch the light performatively—many were sculpted by the same artists who filled Eixample courtyards with allegorical nudes. Even in death, the Catalan elite couldn’t abide understatement.

I was alone for most of my visit. In three hours, I saw exactly two other (living) humans and at least two dozen seagulls, all of whom seemed to be following me. Nothing says "funerary ambiance" quite like the sound of flapping wings echoing through empty terraces. The cemetery's paths twist and loop back on themselves, so you start to feel watched by the statues and pursued by the birds. A weeping marble angel stared at me from every turn, each one more committed to melancholy than the last.

It’s hard not to read the place as a sequel to the city itself. The same materials, the same ambition, the same competitive display. A local saying from back in the day held that if you didn’t own an apartment on Passeig de Gràcia, a villa in Collserola, and a tomb in Montjuïc, you weren’t really anyone.

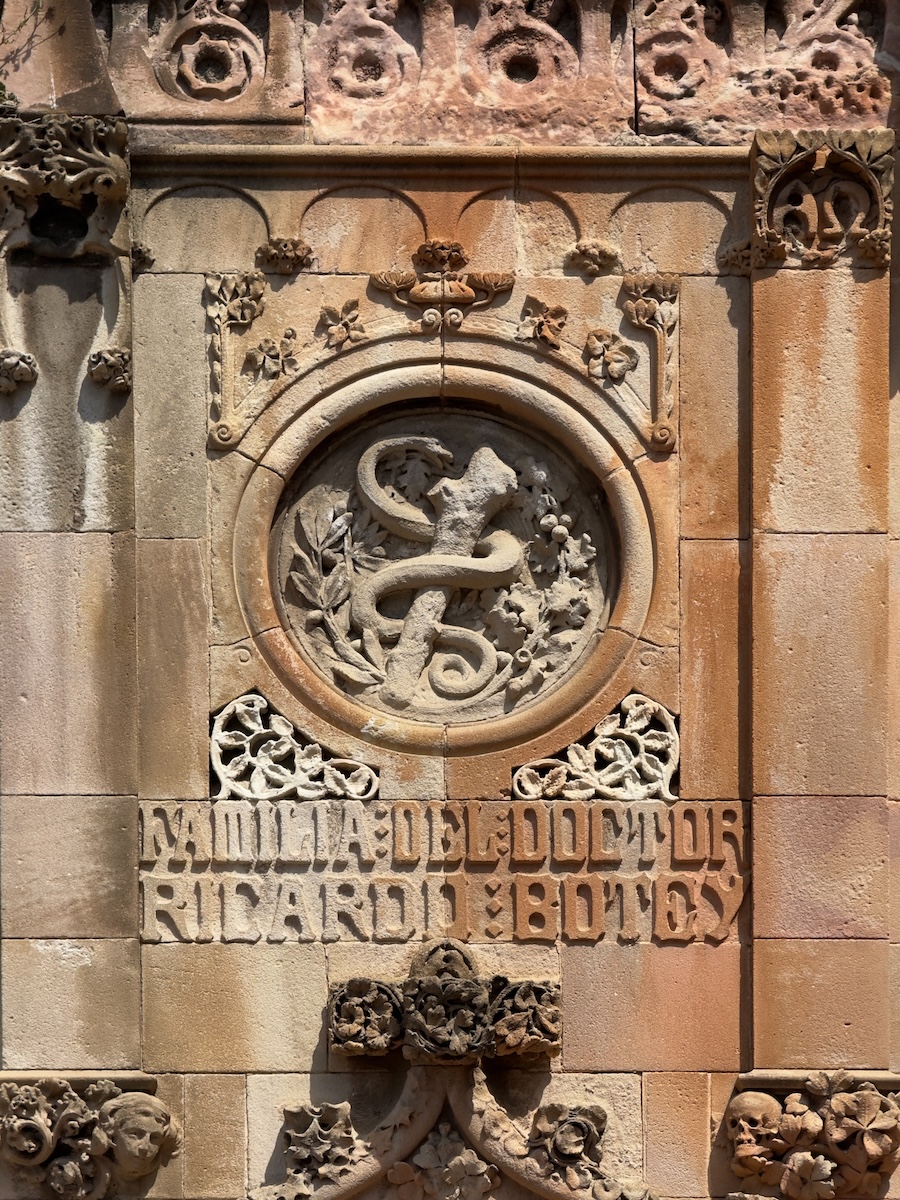

Walking among the mausoleums, that hierarchy still hums. The Bertrand family’s stone façade could double as a Modernista townhouse. The Casanovas' vault looks ready to charge rent. Someone even built a pyramid, complete with a winged solar disk—proof that Egyptomania had reached into Catalonia, too. Elsewhere, gargoyles crawl around columns, mouths open mid-scream, as if warning the living not to cheap out on their commissions.

But there’s grace here, too. The hill faces south toward the sea, and gulls ride the updrafts while cypress trees whisper between terraces. Cats nap on the warm stone benches carved into every wall. I sat on one halfway up, sweating through my shirt, trying to decide whether the view was worth more climbing. It was. The Mediterranean shimmered, cargo cranes standing guard over the harbor that made all these families so rich. Half a mountain later, I understood why the dead stay put. Gravity, I’m guessing.

The higher you go, the more middle-class the population becomes. Near the summit, in a quiet western hollow, lies El Fossar de la Pedrera—the Quarry Grave. After the fall of Barcelona to Franco’s forces in 1939, thousands of executed Republicans were dumped here in mass graves. Anarchists, teachers, unionists, and even Lluis Companys, the president of Catalonia shot in 1940 after being handed over by the Gestapo, rest here. The site is now a memorial to victims of fascism, the Holocaust, and the 1936 social revolution. It’s sparse—grass, granite, a few wreaths—and feels worlds away from the marble opera unfolding elsewhere. The bourgeois tombs shout. This one simply breathes.

Somewhere down the slope lie other notables. Ildefons Cerdà, the city planner who imposed the Eixample grid. Isaac Albéniz, whose piano music still sounds like sunlight. Joan Miró, whose grave is almost shy. And Enriqueta Martí, the so-called “Vampire of Barcelona,” accused of kidnapping children for potions and profit before being lynched in prison. She ended up in a common grave, a macabre footnote to all the marble perfection above. Montjuïc contains every version of the city—the visionary, the artist, the zealot, the monster. It’s a whole civic history carved into one hillside.

By mid-afternoon, the heat had become ridiculous. The stairs, made of the same honey-colored stones used for the walls and niches, reflected the sun like an oven. I passed a statue of a man breaking free from his shroud, muscles taut, halfway between resurrection and rebellion. He looked exhausted. Same. It was time to go.

Despite its size, the place feels largely forgotten. It looks like a few mourners deliver flowers and depart, leaving just silence and the hum of cicadas. It’s astonishing that so few visitors bother to come. But if you want to see Barcelona stripped of pretense, this is where to do it. Every artistic movement that shaped the city—Modernisme, Noucentisme, even bits of Art Deco—rests here in chronological order, sun-bleached and flaking, as if waiting for a docent who never arrives.

I followed the zigzagging path back toward the gate. The air smelled of dust and salt. Ships eased into port below, and the city carried on pretending it was immortal. Up here, the evidence suggested otherwise—but beautifully so.

In Barcelona, even death has a sea view. And, naturally, an architect.

Write a comment