If you’re hurrying between the Gothic Quarter and the Eixample along the busy Via Laietana, you could miss the Palau de la Música entirely. It sits half-buried in the Sant Pere district, where the streets are narrow and the sunlight rarely hits the pavement. Then, between bakeries and apartment balconies, a riot of glass and tile appears—a jewel box jammed into a side street. There’s no way to step back far enough to see the façade all at once. The only UNESCO World Heritage concert hall in the world somehow hides in plain sight—Barcelona’s best magic trick.

Built between 1905 and 1908, the Palau was designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, one of the "big three" of Catalan Modernisme, along with Gaudí and Puig i Cadafalch. But where Gaudí reached for the divine, Domènech built for the people. Well, that’s what he said, anyway.

The Palau was commissioned by the Orfeó Català, a choral society formed to revive and preserve Catalan language and music after generations of suppression. These weren't nobles funding vanity projects—they were teachers, tailors, shopkeepers, whoever had a few pesetas to spare, all pitching in for something larger than themselves. A sort of pre-internet GoFundMe, with an entire region chipping in for a “people’s palace” that ended up looking like the inside of a Fabergé egg.

The façade tells the story of Catalunya in code. On the corner, sculptor Miquel Blay created a sculptural mass called La cançó popular catalana—Saint George leading a crowd of peasants, sailors, and children, all clustered under an allegorical figure of Music. The scene echoes the spirit of Els Segadors, the Catalan national anthem whose origins go back to a 17th-century peasant revolt. The anthem's title means The Reapers, and its lyrics describe the moment ordinary workers rose up against royal conscription. Here they are again, immortalized in stone, forever singing their way out from under Spanish rule.

It’s almost impossible to photograph the façade—two narrow streets converge on it like closing jaws—so you end up with fragments, a column, a violin, a glimpse of mosaic. Maybe that’s appropriate. The Palau was never meant to be viewed from a distance. It’s a building designed for the people inside, meant to be felt rather than seen.

The real shock comes once you’re inside. You step first into a low, vaulted entrance hall—arched ceilings, brick columns, and a flicker of stained glass catching whatever daylight finds its way in from the street. It feels almost subterranean, a modest prelude to what’s coming. Then the space opens, and the marble staircases take over—twin flights curving upward in luminous symmetry, sweeping past ironwork and mosaic toward the rehearsal rooms and concert hall above.

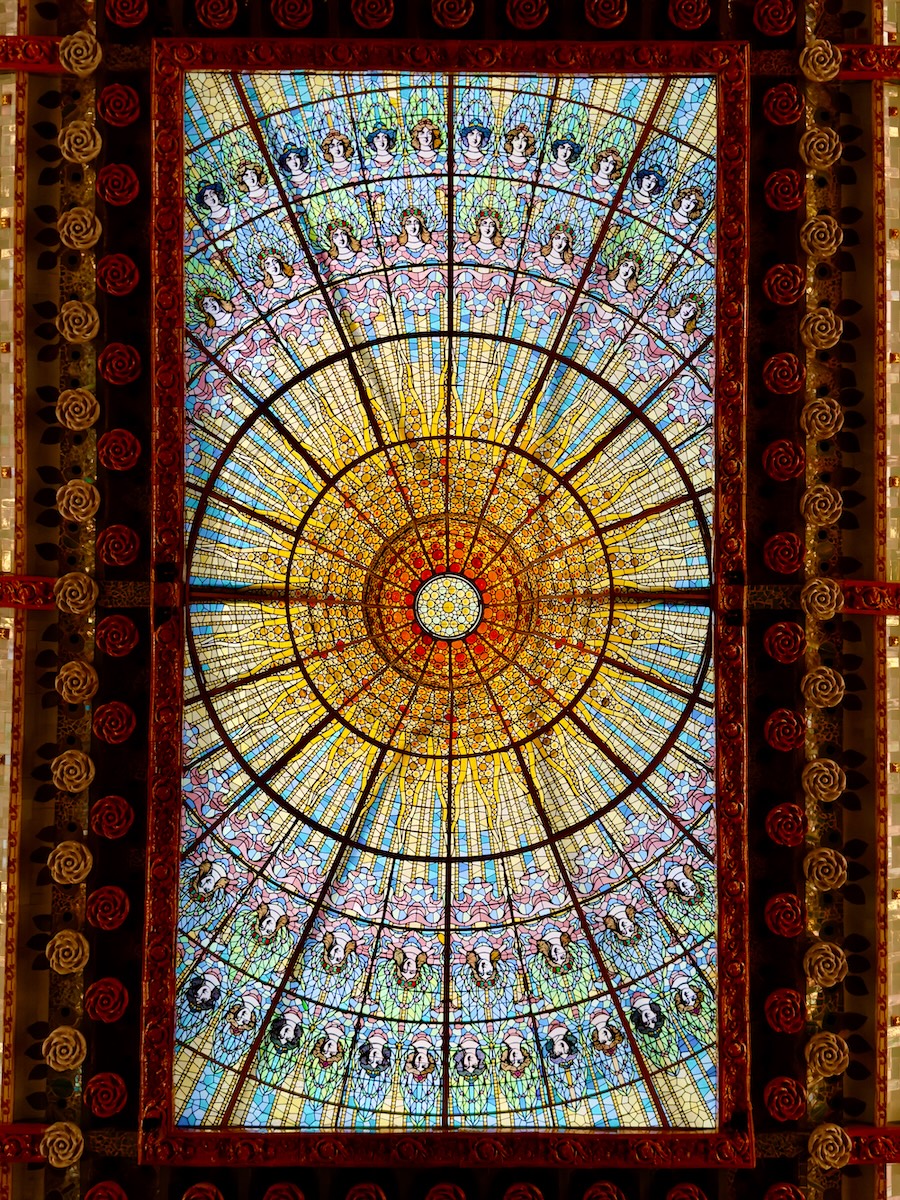

You climb as the light changes from natural to supernatural. Then the doors open, and you’re hit with it—the glittering highlight, the auditorium. A stained-glass greenhouse for music. The ceiling is a swirl of blue and gold centered on a massive, inverted dome of glass—the famous skylight that drips light into the hall like honey. More than 2,000 plush, red-velvet seats sit beneath intricate floral designs, fan vaulting, and a kaleidoscope of colored tiles.

Around the edges, 18 allegorical figures representing music play instruments from every corner of the world, their stone bodies dissolving into mosaic. Figures inspired by Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries add to the sense of drama that pervades the hall. To one side of the stage stands Josep Anselm Clavé, champion of Catalan folk music. To the other, Beethoven symbolizes music as the universal language. Between them looms an organ with 3,700 pipes, ready to rattle your teeth—and your ribs.

It’s overwhelming. The first-time visitor looks up, then around, then back up again. Everything is covered—with roses (there are more than 2,000 of them carved throughout the building), vines, palms, and fruit. The hall is part church, part jewelry box, and part hallucination. And it all works.

If you need to take a breath after all that, Lluís Millet Hall is an oasis. Named for one of the Orfeó's founders, this hall glows behind great stained-glass windows, offering a quiet place for intermission conversations or just coffee. Downstairs, the Foyer Café serves lunch under Modernist vaults that make even a sandwich feel fancy.

The Palau's history has hit some dissonant notes. Under the Franco regime, Catalonia's language and symbols were banned. Then came May 1960. The Palau was hosting a government-approved concert in honor of the poet Joan Maragall, when the crowd began to sing Els Segadors. It was an act of rebellion disguised as a hymn, and the police rushed in to stop it. The event became known as the Sucesos del Palau—the Palau Incident—and it marked one of the earliest public cracks in Franco's rule. Several participants were arrested, including a young activist named Jordi Pujol, who would later become the president of Catalonia.

Decades later, the Palau found itself in the headlines again, this time for less noble reasons. In the late 1990s, its longtime president, Fèlix Millet—descendant of one of the original founders—was caught embezzling millions of euros from the Palau's foundation. He used the stolen money for homes, travel, and the kind of luxury goods you buy when you think Rick's not looking.

It was a gut punch for an institution born of civic generosity and pride, and the trial dragged on for years. Ironically, in 2025, the Palau itself bought back Millet's confiscated mansion to resell and recover some of the lost funds. Catalan poetic justice, heavy on paperwork.

But the Palau endures, as Barcelona itself tends to. The main hall still comes alive night after night, with more than 600 concerts a year, drawing hundreds of thousands from every corner of the world.

The Palau’s power isn’t just in the music but in the tension between extravagance and defiance, civic pride and human frailty. The Palau is as Catalan as it gets—idealistic, headstrong, occasionally scandalous, and always louder than it needs to be.

Step outside again, back into the cramped streets, and the building seems to fold up behind you like it was never there. But it is—and always will be. A palace for the people, built on song, scandal, and the stubborn belief that beauty itself can be a form of resistance.

Write a comment