Walk up Avinguda Gaudí with the Sagrada Família looming behind you, and another kind of landmark takes over the horizon—an entire campus of gardens and red-brick pavilions crowned with tiled domes. It looks like a royal estate, frankly, but this was never built for counts or kings. It was once Barcelona’s main public hospital, at least, until recently, when work moved into a more modern facility next door.

The man behind it (“it” being the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau) was Lluís Domènech i Montaner, one of the leading figures of Catalan Modernisme, best known for the Palau de la Música and Casa Lleó i Morera. For Sant Pau, he imagined not a single stone block but a "garden city" of healing. Domènech believed hospitals should be beautiful, that light and color could contribute to healing as much as medicine. He designed Sant Pau as a collection of separate pavilions, each devoted to a specialty, surrounded by gardens, and all connected by underground tunnels. He planned for 48 buildings, and 27 made it off the drawing board. Spread across nine city blocks, it is now the world’s largest Art Nouveau complex.

The city needed it. By the late 1800s, the medieval Hospital de la Santa Creu, which had been operating in the Gothic Quarter since the 1400s, was in dire need of an update. Enter Pau Gil i Serra, a Catalan banker residing in Paris who died in 1896, leaving a substantial fortune to establish a new hospital. He had only two stipulations—that it should be dedicated to Saint Paul, and it should represent the very best of modern medicine and architecture. His money—three million pesetas—was enough to make it happen. Ultimately, though, Sant Pau was built by the city itself—Catalan families, institutions, and even anonymous citizens added their own contributions, large and small, to turn the plan into reality.

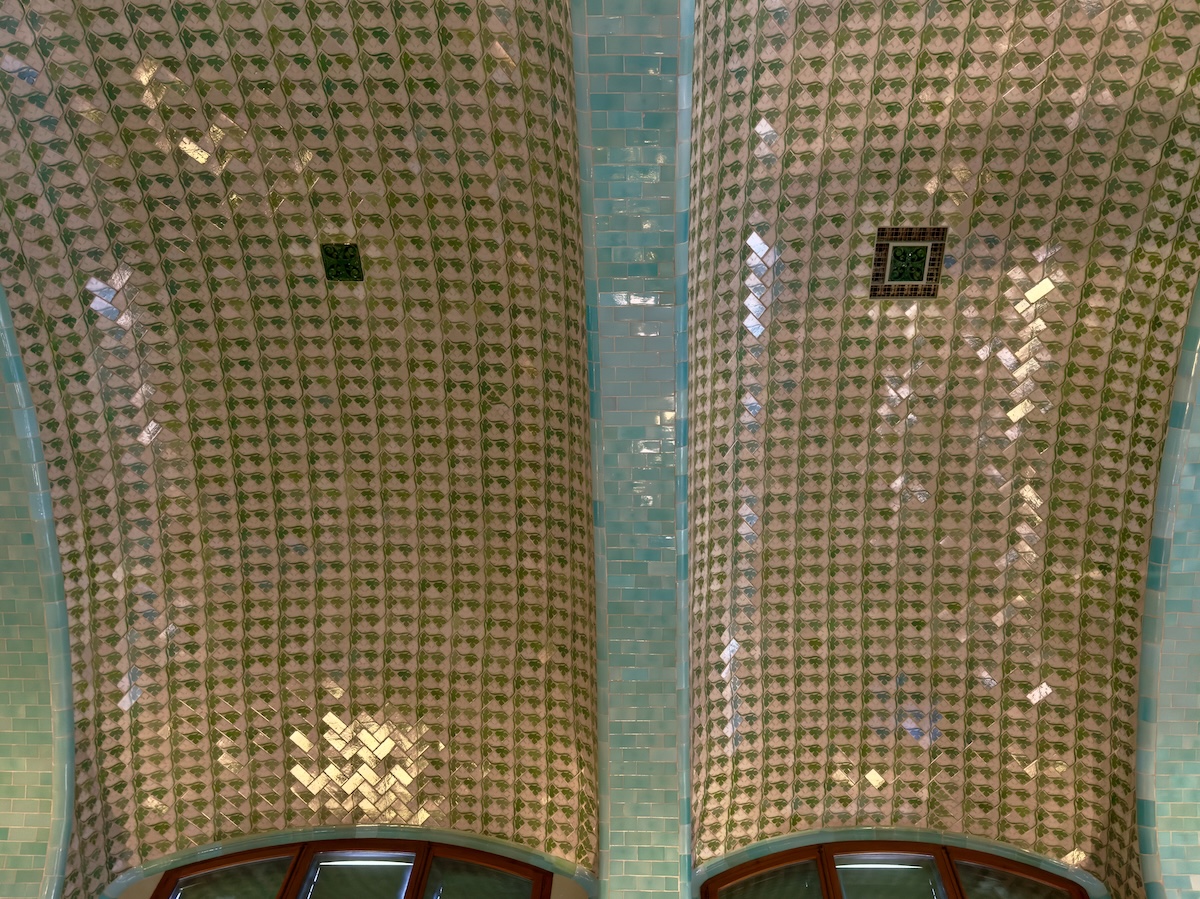

The centerpiece is the administration building, topped by a 200-foot clock tower and adorned with mosaics and stained glass, and featuring sculptures of saints, virtues, and Catalan heroes. It’s not your usual entrance hall—it looks more like an altar, an architectural sermon on the civic virtue of health. Beyond this building, the wards unfold pavilion by pavilion, inching up the hill behind the entrance, each dome tiled in its own pattern. Inside, ceramic walls weren’t merely decorative—they could be scrubbed clean daily, and some panes of century-old handmade glass still ripple sunlight unevenly across the floors. Floral motifs, skylights, and stained glass made the place feel anything but clinical. And tucked among it all, as always, is Catalonia’s favorite myth—St. George and his dragon—rendered in tiles and sculpture as if to suggest that even illness could be slain with enough civic pride.

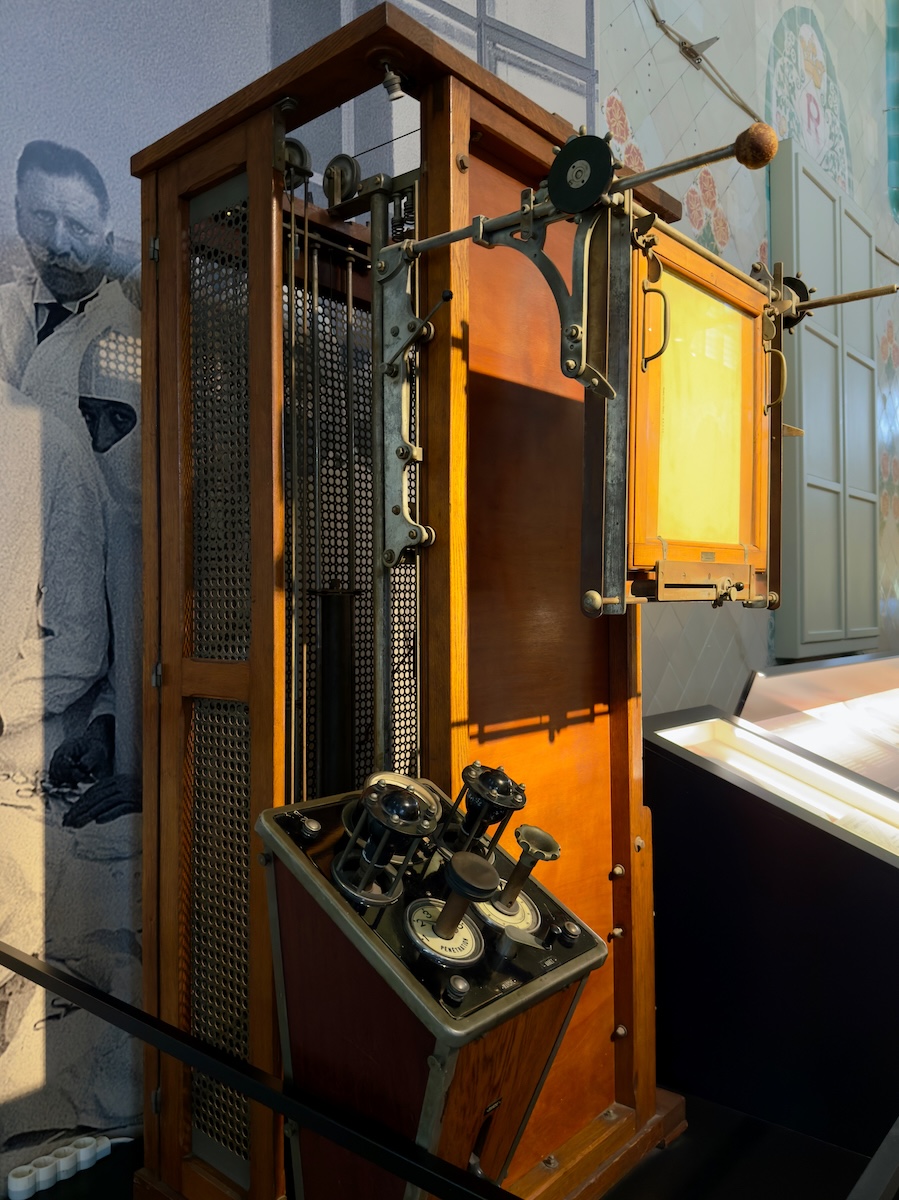

That beauty didn’t shield Sant Pau from history, though. During the Spanish Civil War, it was seized by the Generalitat and renamed the General Hospital of Catalonia. In the decades that followed, it modernized steadily, adding the country’s first coronary unit, then pioneering bone marrow and heart transplants. By the early 2000s, though, the facilities were definitely showing their age. By 2009, the hospital's daily work moved into new facilities built on the northern end of the property, leaving the Modernista part of the complex free for restoration.

That’s when Sant Pau became a museum piece in the best possible way. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997 (along with Domènech’s Palau de la Música), the complex reopened to the public in 2014. It now houses cultural institutions and hosts conferences, but mostly it’s a place you can wander at your own pace, moving between gardens and tiled interiors. The old tunnels—once marked with color-coded stripes to direct patients—are part of the tour, as is the Hypostyle Hall, with its forest of columns. A former seminar room boasts a circular stained-glass skylight big enough to pass as a flying saucer. And from the main steps, you get a perfect line of sight back to Gaudí’s basilica. The two sites have been linked since 1926, when the city cut Avinguda Gaudí straight between them, a civic boulevard that made their architectural rivalry impossible to ignore.

Sant Pau doesn’t get the same crowds as its famous neighbor, making it a Modernista masterpiece you can actually enjoy without elbowing through a tour group. A hospital dressed like a palace, still making the case that beauty really can heal.

Write a comment