The Palau Nacional sits at the very top of Montjüic, visible from nearly anywhere in Barcelona. When you see it from the bottom of the hill coming up out of the metro, it positively looms, looking like it’s been dropped there by an emperor with something to prove. It was built for the 1929 International Exposition and never taken down—it’s hard to imagine anyone daring to move it.

Today it houses the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (MNAC), and from that first glimpse, it feels both improbable and inevitable. Of course this was going to become Barcelona’s great art museum. Where else would you put such a sprawling collection except in a palace halfway to the clouds?

Getting up there requires a strong constitution and good knees. The official approach is a terraced spine of fountains and stairs—majestic, symmetrical, wildly impractical. But modernity has stepped in with a series of outdoor escalators. We’re no dummies, so we took them.

The building itself is monumental Beaux-Arts. Inside, though, it's all marble corridors, soaring ceilings, and galleries tucked behind thick arches. You feel small. The collection spans a thousand years of Catalan art, from the fantastical beasts of medieval churches to the sleek lines of Gaudí's furniture. But you don't just move through time here. You shift in tone.

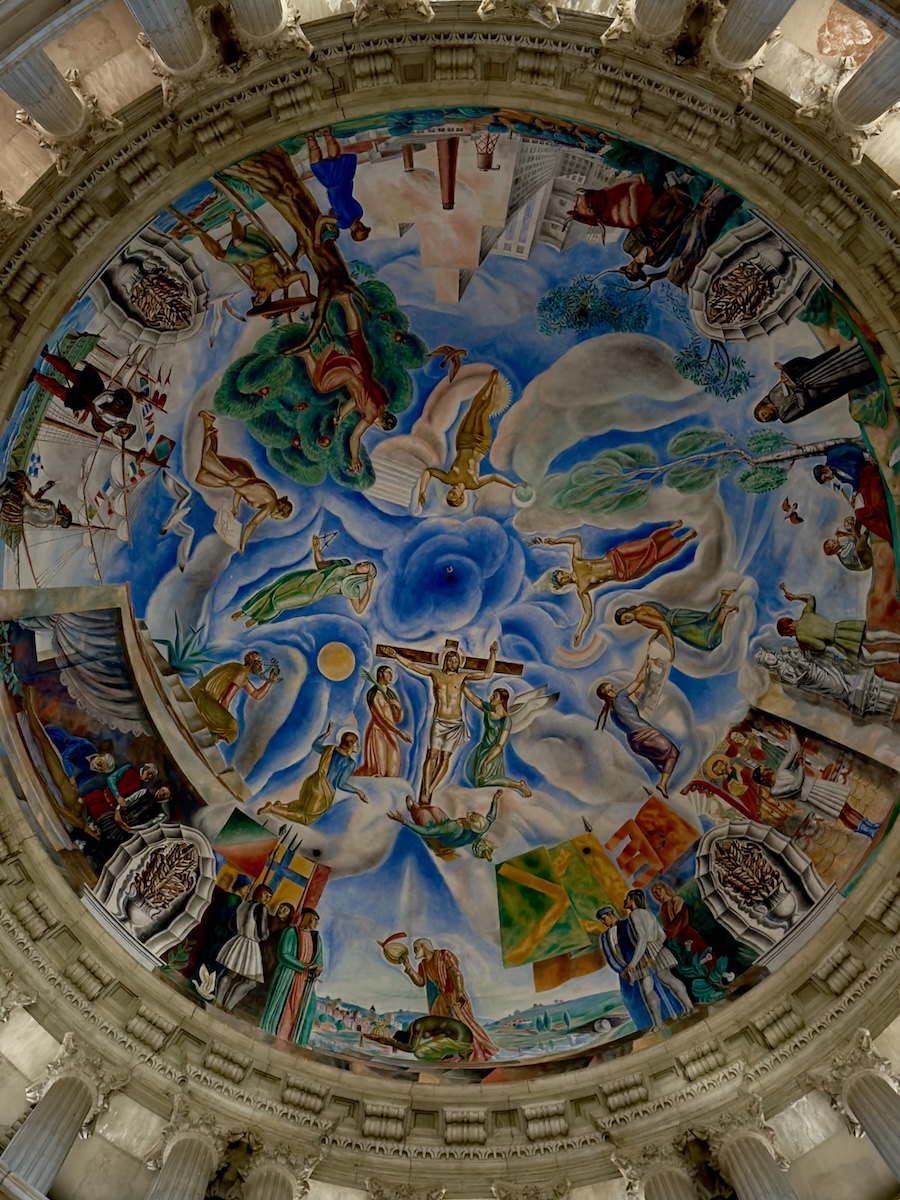

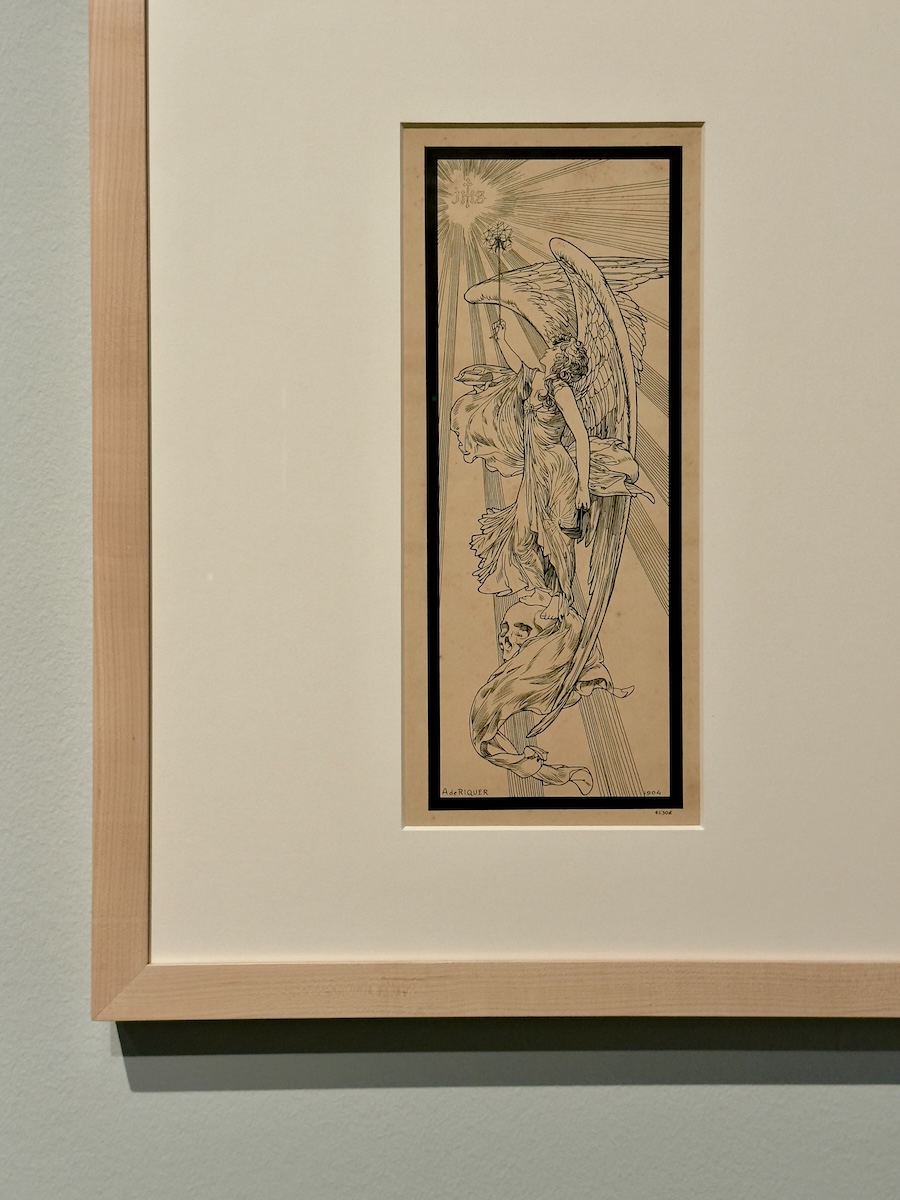

We started upstairs, where the modern art is staged in tall, light-filled rooms. There’s a lot to love here, with paintings by Ramon Casas and Joaquim Mir, avant-garde furniture, and entire living rooms lifted from the Modernisme era. One standout was the Dome Room, which crowns the Palau by Francesc Galí, one of the most important Catalan artists of the 20th century—a dazzling, moody composition featuring 35 allegorical figures of the Fine Arts, Science, Religion, and the Earth that was cosmic and a little disorienting. Beneath the fantastic murals are sculpted personifications of Work, Religion, Law, and Order.

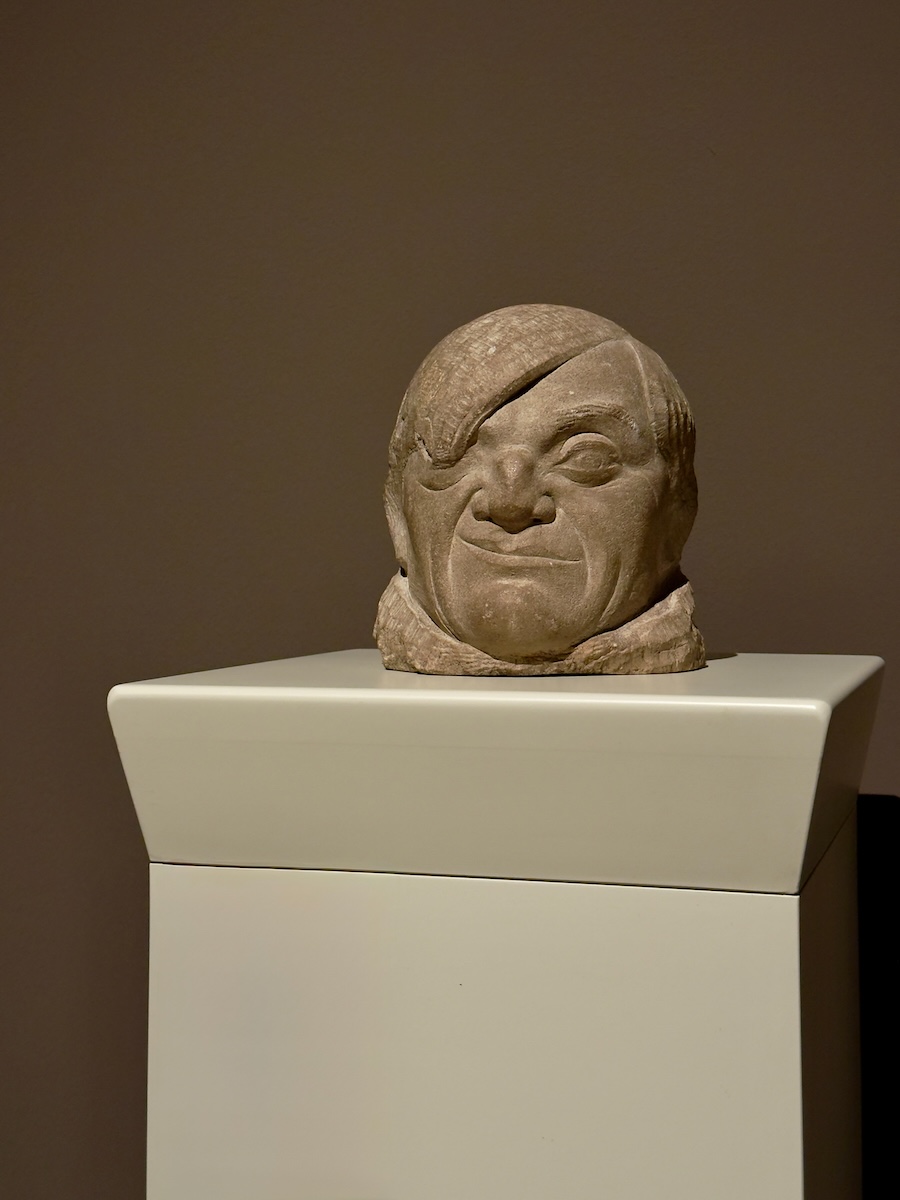

From the Dome Room, the galleries lead you through the dense theatricality of Modernisme into something looser and stranger. The furniture thins out. The color palettes shift. Noucentisme sneaks in—not a clean break, but a creeping rebellion. Gone are the overwrought flourishes of Art Nouveau, replaced by irony, structure, and early shocks of surrealism. Included here was a wry sculpture titled Drunk from the Stair Knob of the Cellar of the Galeries Laietanes, which manages to be both visually surreal and precisely what it claimed to be.

Tucked quietly among the louder works was a painted screen by Enriqueta Pascual, one of the rare named women artists of the Modernisme and Noucentisme periods. The subject is neither heroic nor mythological—it shows the Calaf Market in 1929 with local women shopping at produce stalls under soft Mediterranean light, rendered on silk with delicate gouache. It doesn’t shout—but it does linger.

Just when you start to settle into the elegance of curved wood and moody oils, the museum throws a punch. The Spanish Civil War section is filled with historical propaganda posters—workers with hammers, red stars, bold slogans, threats, and promises in equal measure. Off to the side, a quieter wall delivers a series of lithographs from Bestiario del Laberinto Español by Ramon Puyol, each depicting a different psychological or social type from the war years—including The Pessimist, The Rumor, The Defeatist, The Hoaxer, and The Spy. They’re grotesque and absurd, caricatures uncomfortably close to current events.

From there, we passed through the Sala Oval—a vast central hall once meant for grand gatherings and state pageantry. Natural light filters in from the dome overhead, and a massive pipe organ—roughly 112 feet wide and 36 feet high—looms above the space like it's waiting for a cue. These days, it's mainly used for concerts, though it's easy to imagine it being used to open a session of parliament or drowning out dinner at a gala.

The Renaissance and Baroque galleries came next—saints and sinners, fruit bowls and martyrdoms, and more Saint Georges than you can count. There are also several Velázquez and El Greco works to remind you the museum means business. The Gothic galleries had more local flair—altarpieces with wide-eyed saints and architectural fragments that felt both excavated and staged.

We took a break in the restaurant, which is worth mentioning here for three reasons—the food was actually excellent, the prices were not absurd, and the view over the city was so clean and grand it felt unreal. Barcelona stretched out below us like a promise.

Then we hit the Romanesque wing on the ground floor. It is spectacular.

The frescoes here aren’t just wall fragments or isolated panels. These are entire church interiors—apses, arches, and vaults—reconstructed inside the museum like sacred dioramas to display frescoes peeled off their original stone walls and reassembled here. It’s not a metaphor. In the early 20th century, scholars and conservators literally lifted paintings from crumbling Pyrenean chapels to save them from weather, theft, and at least one American collector with a virtually unlimited shipping budget. (Boston got two.) What followed was an urgent campaign of preservation—experts removed the paintings section by section, mounted them on curved frameworks mimicking the original architecture, and installed them here in near-life-size reconstructions.

The result is astonishing. You walk into these dim, curved spaces and feel like you've slipped into the body of a medieval church. A video in the gallery shows how the transfers were done—it looks reckless and almost violent. But the outcome is one of the most immersive Romanesque collections in the world.

Inside each apse, monsters leer from archways, Christ floats in almond-shaped halos, and saints hold poses as if they're doing medieval yoga. The figures are stylized, flattened, and often strange. One horse looks like a beaver. It is glorious.

And a perfect ending to an awe-inspiring museum. It could be the contrast. Inside is a thousand years of Catalonia trying to define itself through art—saints, slogans, and sofas. Outside, the city stretches below you like a mosaic, a little fractured, mostly beautiful, and constantly shifting.

From the towers below to the frescoes above, this place asks you to climb—and rewards you for it. And if your legs are tired, there’s always an escalator.

Write a comment