God only knows where I heard about the studio of Oleguer Junyent in Barcelona, but I was excited to go. Even though I knew where I was going this time, there were a few minutes there where I wasn’t entirely sure I’d gone to the right place. The studio is located in a residential building on Carrer Bonavista, but its name is not listed in the directory. At all. So I stood awkwardly by the curb, poking at my phone, debating whether—and how—to send a note.

Hardly the kind of signage you’d expect for one of the city’s most remarkable private collections.

The door opened, though, and I ended up chatting with the lovely Sabine Armengol (Junyent’s great-grand-niece, who manages the place these days) while we waited briefly for the other two guests who’d signed up for the tour that day. I say “tour,” but it was more like a lovely visit with an effusive friend who’d asked you over to see her favorite uncle’s crazy place.

Oleguer Junyent (1876–1956) was a man who seemed determined to do absolutely everything cool in life. He was a painter, an interior decorator, a costume and set designer, and a world traveler. He took a trip around the world in 1908 that resulted in a treasure trove of drawings and photographs. He was also an author, a photographer, and a collector of medieval art—all while carving out time to be a star in the firmament of Barcelona’s social circuit. I’m sure I would’ve liked him.

Originally, Oleguer wanted to be a painter. But his older brother Sebastià already had that slot covered. His parents’ attitude was that one starving artist in the family was amusing, but two was a problem. So they pushed him toward stage design, which, unlike painting, paid good money. And Oleguer was good at it, really good. He made a name for himself designing sets for the Gran Teatre del Liceu, where in 1913 he staged Wagner’s Parsifal—the first time it was performed outside Germany. He was suddenly in demand across Europe, but he saved his best for Barcelona. He also turned his hand to interiors, helping decorate Casa Burés and the Cambó residence, blending Wagnerian imagination with bourgeois opulence.

Both interior design and scenography require stuff, lots of stuff—props, relics, costumes, art pieces—and Oleguer started collecting with gusto. What began as acquiring stock for his design work turned into a lifetime of accumulating everything from medieval reliquaries to 19th-century automata. The irony is that just as his hoard was getting interesting, the work that justified it was drying up. By that point, the props had become the main event.

By the early 1920s, film was eating theater’s lunch, thinning out demand for Junyent’s painted backdrops and extravagant sets. Also, Sebastià had died at the tender age of 33 in 1898, so the “no second painter in the family” rule no longer applied. So Junyent picked up a brush and began turning out canvases with the same energy he once spent on sets.

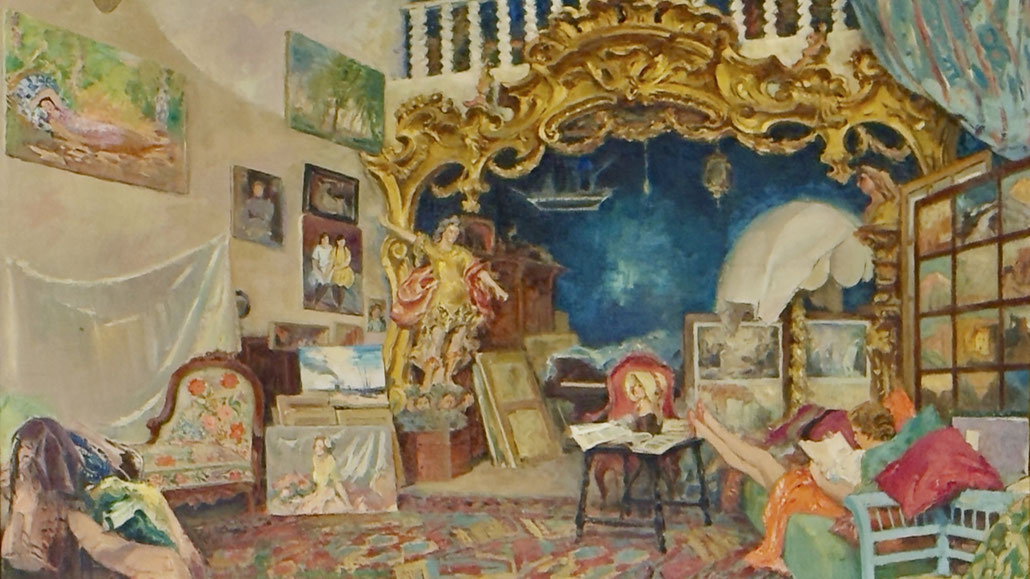

The studio holds evidence of all those pursuits—paintings, sketches, scale models, set designs, and odd props that look like they’re waiting for a curtain to rise. It’s less polished than a museum and more alive because of it. The space is pure Belle Époque, with high ceilings, tall windows, walls lined with bookcases and cabinets stacked with reliquaries, caskets, carved saints, and wrought-iron locks. Junyent collected with the same appetite he brought to everything else. Arnau Bassa and Lluís Borrassà—two names from the golden age of Catalan Gothic painting—hang on these walls as casually as if they'd been picked up at a weekend flea market.

One piece in particular stopped me—a Baroque statue by Luisa Roldán (also known as La Roldana). She was the first woman ever appointed sculptor to the Spanish court in the 1600s, carving her way into a profession that rarely admitted women at all. Seeing her work tucked among the reliquaries and Gothic panels in Junyent’s studio felt like spotting a rare crack in the wall of art history—proof that someone had managed to push through.

But the atelier doesn’t end with Oleguer. Upstairs, his niece Maria Junyent added her own obsessions—more than 200 dolls and automata from the 17th through 19th centuries, plus theatrical costumes from rococo frills to art deco gowns. She worked as a costume designer herself, and her collection has the slightly theatrical air of a wardrobe room, complete with figures ready to be wound up and set dancing. If you’re very lucky, Armengol, the great-grand-niece whose name is on the buzzer, will demonstrate a few of the automata. They spring into motion with a whir and a click, halfway between charming and eerie. One even smokes! At least the automata never hesitated when someone pressed their button.

Armengol and her sister’s families still live in other flats in the building, and they’re the ones who’ve kept the studio open. With each generation, though, the collection contracts. Inheritance taxes in Barcelona are steep, and the family has had to part with a few treasures each time the estate changes hands to pay the bills. So if you’re tempted to visit, don’t wait too long.

Visiting the Estudi Oleguer Junyent is unlike the rest of Barcelona’s cultural circuit. There’s no crowd management, no light show, no gift shop. Just an atelier that feels intact, layered with art, travel, theater, and family memories. And yet, to see it, you still have to ring a buzzer with somebody's surname on it, hoping you've picked the right one. Barcelona's got blockbuster attractions with lines around the block, but one of its richest collections only affords entrance with a mundane ring of the doorbell.

Write a comment