I went to Palau Güell in Barcelona twice. Once during the day, and again on another evening for a tour that wound its way through areas not typically open to the public—the roof, the attic, and a few work‑only corridors. Seeing it twice made it clear that this was Gaudí before the froth—closer in spirit to his lampposts on Plaça Reial (his first Barcelona gig) than to the candy‑shell rooftops up on Passeig de Gràcia. Built between 1886 and 1890 for Eusebi Güell, the industrialist who became his patron-for-life, this house is dense, vertical, and, let’s face it, pretty severe for a family palace.

Their story started, improbably, with a display case Gaudí designed for a glove maker’s booth at the 1878 World Exhibition in Paris. Swaggering through the hall, Güell stopped cold at the case. It was bold. And odd. And utterly unlike anything else in the hall.

It was also the start of one of the strangest architect-patron marriages in history, and one that reshaped the city of Barcelona. Based on that one shop window display case, Güell handed Gaudí one of the most open-ended commissions imaginable—to build a family palace with a virtually unlimited budget.

The location—in one of the oldest and sketchiest neighborhoods in town—made about as much sense as choosing a relatively untested architect for a palace. So, not much.

While other wealthy families moved up into the shiny new Eixample neighborhood, Güell planted his palace just off La Rambla in the Raval—a neighborhood then better known for music halls, mischief, and…well, let’s just call them seamstresses. It wasn’t entirely whimsy. His father’s house was at the back of the lot he’d purchased, and Güell connected the two with an above-ground passage so the family could visit without walking through the messy, working-class neighborhood below. Family gravity over urban planning.

And the family had gravity. Eusebi was rich on his own, but his 1871 marriage to Isabel López Bru supercharged his fortune. Isabel’s father was Antonio López, first Marquis of Comillas, a shipping magnate whose fortune ranked among the largest in Spain. Pile that on top of his father Joan’s textile and banking wealth, and you’re talking dynastic-level resources. Enough to support 10 (!) children and build the grandest house in the Old Quarter.

Of course, even unlimited budgets come with fine print, and Güell did hand Gaudí two design restrictions.

First, there had to be a monumental mural of Hercules somewhere in the house. Why Hercules? Because Barcelona insists he founded the place. After a storm scattered Jason and the Argonauts, Hercules washed up on the Catalan coast. He liked what he saw and, as demigods are wont to do, promptly planted a new city named Barca Nona after his ninth ship.

Academics scoff and point to a Carthaginian origin, but in 19th-century Barcelona, Hercules played better. And for the Güells, hanging Hercules in their central hall wasn’t just about biceps and mythology—it was a way to link their family to the city’s mythical founder. Güell had a three-story copy of the painting on the house’s façade to make sure even the hoi polloi understood that link, though that one has since vanished, victim to the weather and time.

Second, Güell required that every family room have its own fireplace. Eusebi Güell was tired of being cold in Barcelona winters. While he gave Gaudí near-total freedom, he wasn’t about to sacrifice comfort for design. Smart man.

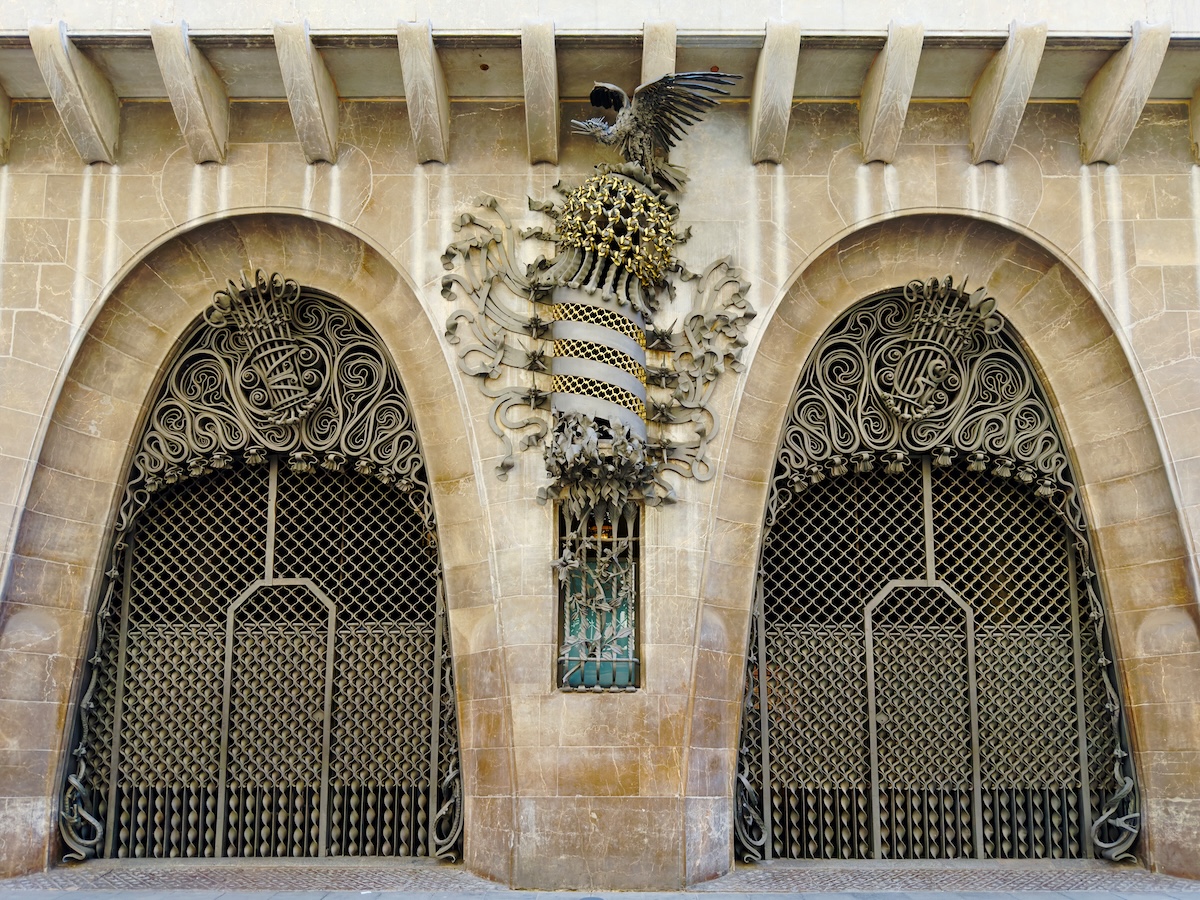

Other than those two specifics, the house was always intended to be equal parts residence for the Güells and their 10 (!) children and a stage for the socially prominent family to impress the locals. And Gaudí delivered. From the outside, the place looks almost reserved—stone façade, Venetian hints, and two great iron gates whose curling filigree seems alive, half seaweed, half smoke.

Carriages didn’t stop at the curb—they rolled straight through the parabolic arches and into a ground‑floor carriage hall and spiraling down to the basement stables after disgorging their wealthy passengers. Our guide pointed out a small landing at the foot of the grand staircase built to match the height of a carriage floor—so ladies could step out without soiling hem or shoe—a tiny Gaudí touch with outsized civility. Gaudí thought about sound here, too. All of the surfaces of the carriage entry, stairs, and stable ramps are designed to keep the clatter of wheels and hooves from booming up into the house. Even today, you can hear how the ramps muffle footsteps, more thud than clatter.

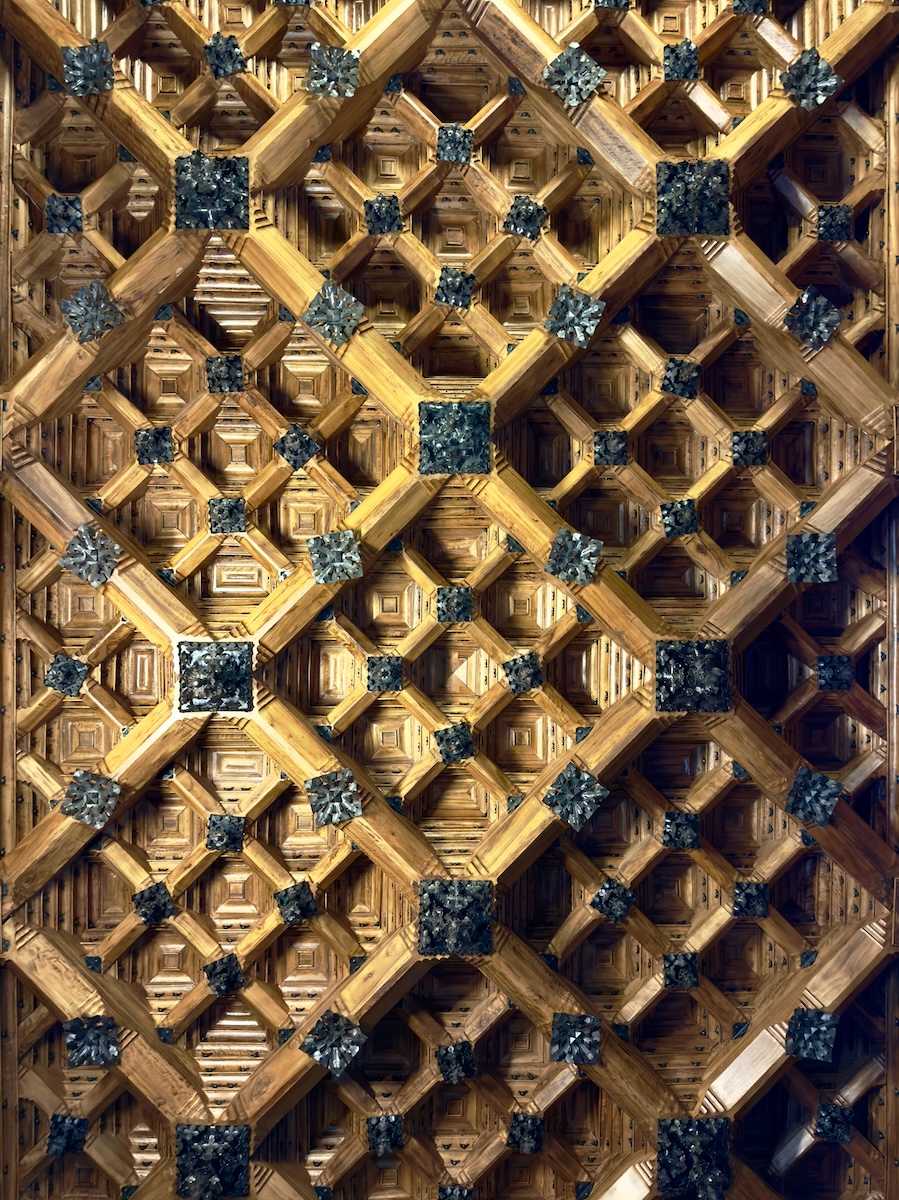

From the civility downstairs, you move to sheer drama upstairs. The interior is organized around a central hall that soars more than 60 feet to culminate in a cone-shaped dome. In daylight, tiny perforations let in scattered sunbeams, and lanterns hung through the holes at night create the illusion of a starlit sky—a Gaudí trick long before he hung fruit baskets off Casa Batlló’s balconies or crowned La Pedrera with stormtrooper chimneys. The atmosphere here is darker, heavier, and closer, but unmistakably his.

Flanked by the formal dining room and a private chapel, the central hall is also where the Güells hosted concerts. Gaudí stacked the performers vertically, with the keyboard just off the central hall, singers on the open gallery a floor above, and the organ pipes tucked just under the attic so music would spill from above and wash over the guests. Essentially, the entire house was an instrument.

One thing I loved because it’s so un‑Instagrammable—the spy holes. The central hall has latticed windows high in the walls so the family could watch arrivals before deciding how to make their entrance. Servants had their own discreet peepholes, too, so they could keep the crowd moving and the pageant running on time.

Also nearly un-Instagrammable is the roof—a forest of chimneys, each different, where Gaudí let himself play. This was Gaudí’s first serious experiment with his trencadís tile technique, long before he unleashed it on Casa Batlló, La Pedrera, and Park Güell. One chimney even hides fragments of a Limoges china dinner set that Eusebi Güell got tired of using. Waste not, want not!

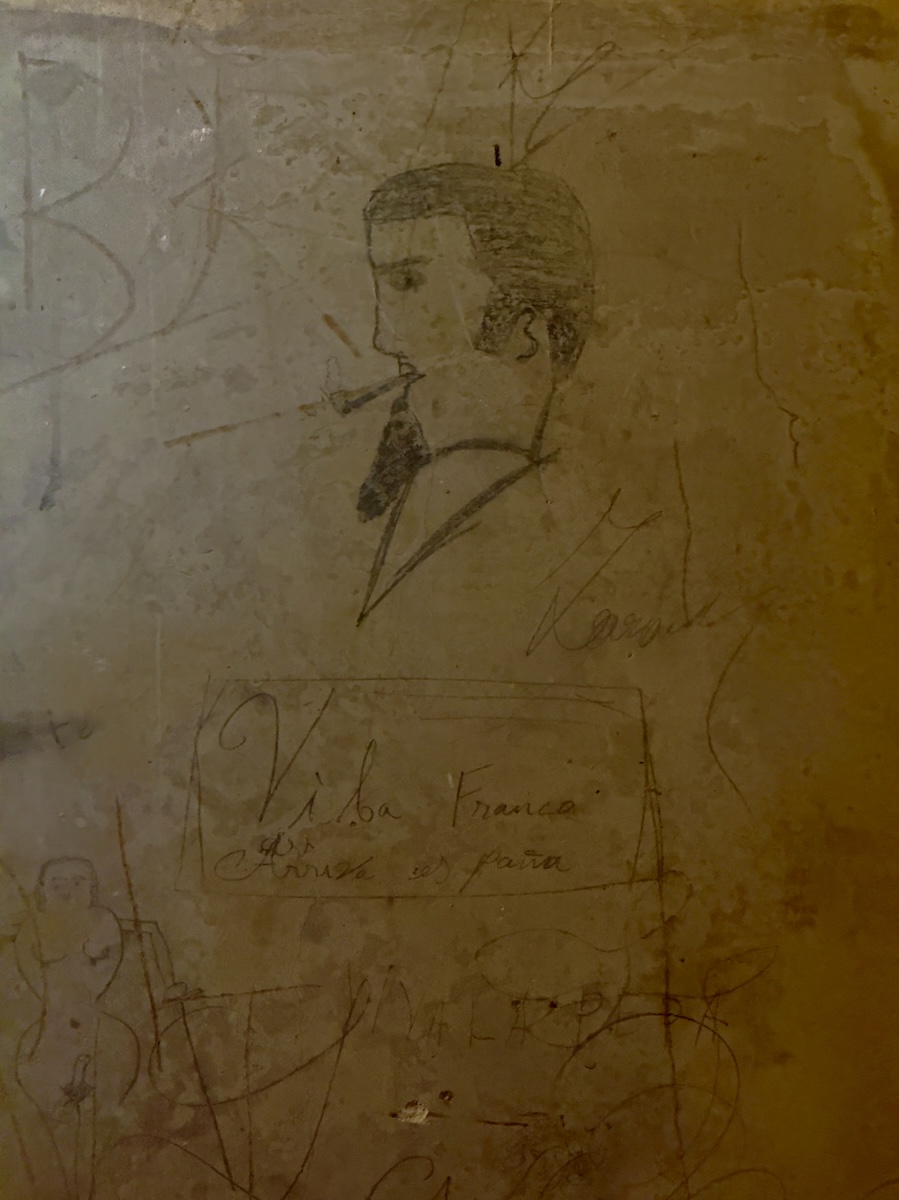

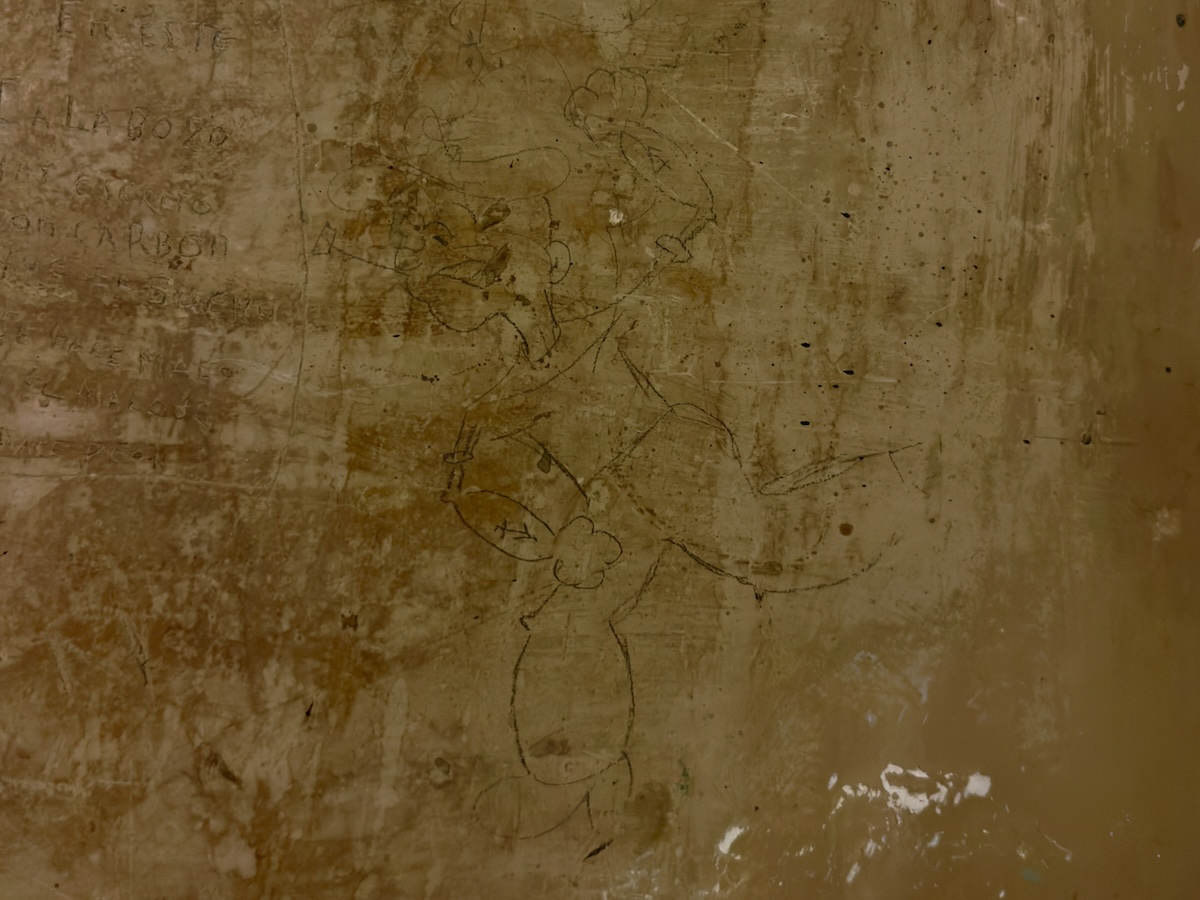

The Civil War between 1936 and 1939 knocked the Güell story sideways. Anarchists seized the house, using it as a barracks and even a makeshift jail. You can still see graffiti in one room, scratched and penciled by prisoners—small, rough, and completely arresting. The house was abandoned when the anarchists left, and the family never did move back in. After years of neglect—and World War II—the youngest daughter, Mercè Güell, formally transferred the palace to the provincial government in 1945 on condition of preservation and cultural use.

The handoff didn't mean instant glory. For a while, the palace limped along with the occasional concert, half-hearted exhibition, and a lot of peeling plaster. The Raval wasn’t exactly drawing preservationists in the 1950s, and Gaudí’s reputation was still building to “global treasure” status— hard to imagine now, when his buildings practically carry the city’s entire tourism infrastructure on their backs. By the 1970s, though, real conservation work had started, slow and piecemeal as it was, but enough to keep the place standing.

UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site in 1984, but even so, the building was showing its age by the early 2000s. That’s when the provincial council launched a full restoration campaign. It took seven years—scaffolding, careful cleaning, and the painstaking reconstruction of chimneys that had crumbled almost beyond recognition—before the palace finally reopened in 2011 looking more or less as Gaudí had intended. And it only took a century, two wars, and one global heritage committee to get there.

Compared with his later confections, Palau Güell feels almost stern. But standing in that central hall at night, looking up at a man-made constellation of lanterns, I could see exactly why Güell stuck with Gaudí through project after project. It was dark, quiet, and—thanks to the acoustics—every cough in the crowd sounded like a cannon. Theirs was a partnership that bore astonishing fruit over the years. And it all started here, steps off the Rambla in a neighborhood that wasn't meant for palaces, let alone one of the strangest and most brilliant homes in Europe. Hercules would’ve approved. The seamstresses, less so.

Write a comment