I didn’t know what to expect at Casa Amatller, but it ended up being one of my favorite stops in Barcelona. I’d scheduled the visit mainly because it was next door to Gaudí’s Casa Batlló—same block, same era—and I figured it would make for a neat compare-and-contrast. Which it did. Dramatically.

At Casa Amatller, I was the only person signed up for the English-language tour, which meant I got a personal guide and a slow, quiet walkthrough of a home that felt like someone might still be living there. At Casa Batlló, which I toured later that same day, I paid nearly twice as much for the “expanded” experience and still got swallowed whole by a crowd of international influencers. No room to breathe, no one to ask questions. Just a lot of elbows and phones and people taking selfies on staircases they didn’t know the name of. Casa Amatller was nothing like that.

As I wandered through the house, snapping photos, I kept wondering: what kind of business was Antoni Amatller in that he could afford a spread like this?

“Chocolate,” my guide said.

I blinked. “Seriously?”

She nodded.

“That’s some spendy chocolate,” I said.

“Well, it was a luxury item back then.”

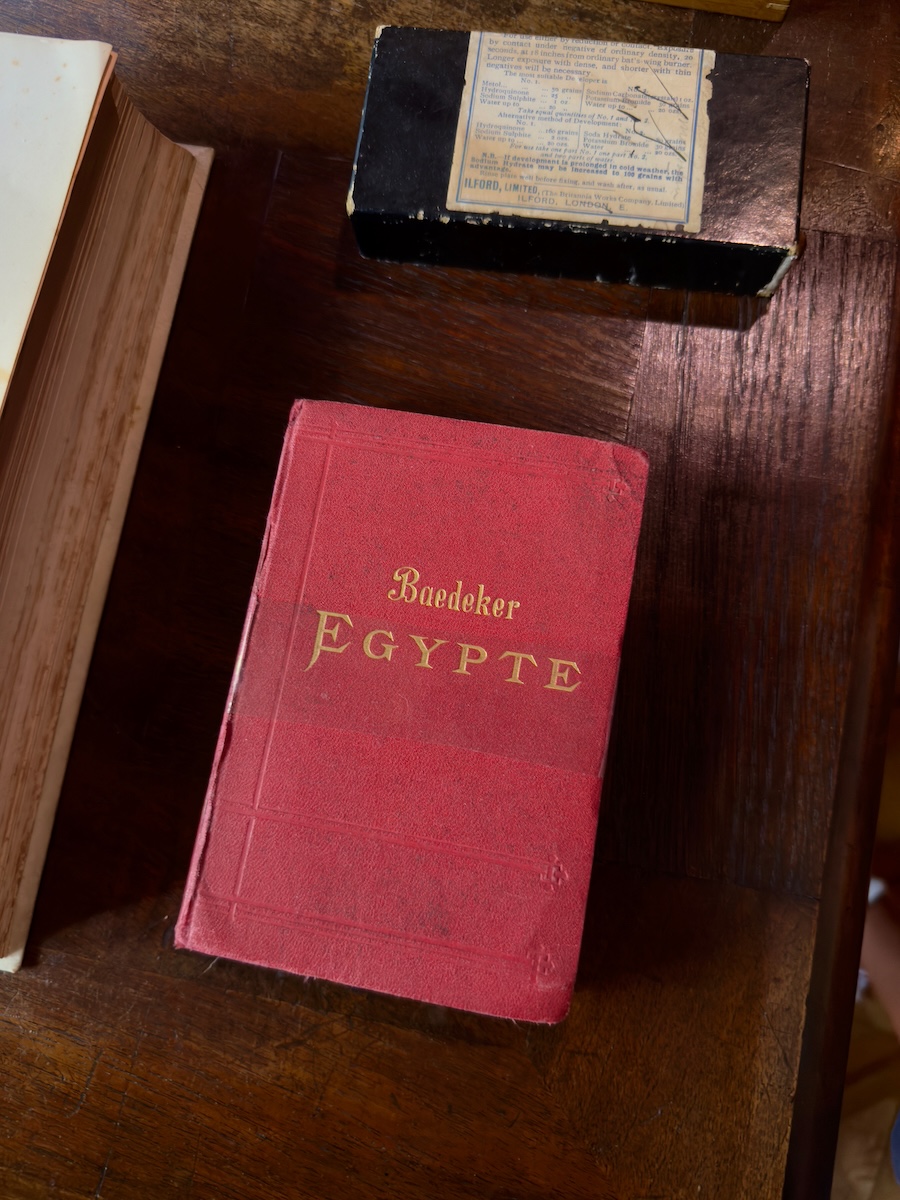

Yeah, even “luxury” might be underselling it. The house he (re)built at the turn of the 20th century with architect Josep Puig i Cadafalch doesn’t just look like money. It looks like a full-on confidence play. The stepped gable façade—more Dutch than Spanish—breaks the city’s building codes wide open, rising past its neighbors in defiance of the neighborhood’s original zoning rules. But the gable’s height wasn’t just about show—it also held Amatller’s private photography studio, tucked safely away from the rest of the house thanks to the lovely but toxic nature of early darkroom chemistry.

The sculpted almond blossoms throughout (a nod to the family name, which means “almond” in Catalan), the fantastical grotesques peering from the windows, the elaborate ironwork and tile—nothing about it is subtle. But, surprisingly, it’s also not loud. It’s balanced. Confident. Baroque without being barf.

And symbolic, too. Near the main entrance, Saint George slays a dragon above a set of carvings depicting the stages of chocolate production. In the bay window overhead—visible from the street—a solitary pink marble column in Amatller’s daughter’s room serves no structural purpose whatsoever. It’s just there to be looked at. To be admired. Which I did, from inside and out.

My visit began in the ground-floor vestibule, where the staff once came and went through what is now a chocolate café. From there, we started the tour by heading up a monumental staircase beneath a skylight so colorful and bright you almost don’t notice the animal-shaped figures along the banister making chocolate.

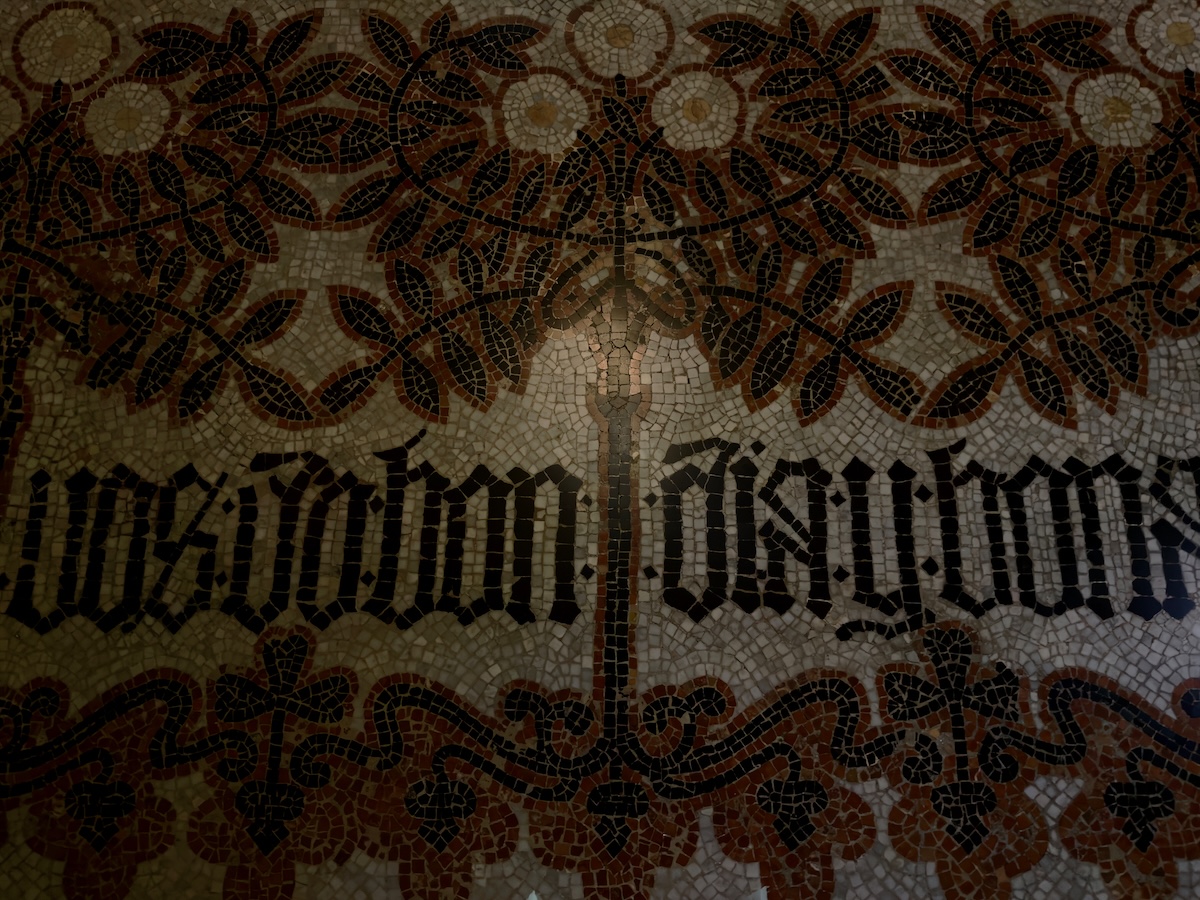

Upstairs, the house opens into a series of beautifully preserved rooms, furnished with the family’s original pieces, and curated with admirable restraint. The kitchen has copper pans and a dumbwaiter system that once ferried food to the formal dining room. The living spaces are a museum-worthy mix of Catalan Modernism, Roman mosaics, stained glass, carved wood, and whatever you’d call a fireplace depicting an Aztec princess shaking hands with a Castilian one. Some sort of conquest-themed cocoa alliance?

Amatller’s study sits like a control tower in the center of it all, giving him sight lines into both the family wing and the servants’ quarters. He ran a tight operation. Even the art collection—assembled with the help of his in-house advisor—follows a clear, thematic brief: Hispano-Roman glass, Gothic altarpieces, and works by artists like Bartolomé Bermejo and Ramón Casas, all still displayed on site. His archaeological glass collection alone could stock a small museum.

His daughter Teresa inherited the house after he died in 1910 and lived there until she died in 1960. She made a few changes—most notably an Art Deco dressing room in stark contrast to the rest of the house’s Modernist style—but kept the main elements intact. In 1939, as Franco’s dictatorship began, Teresa quietly covered over the Catalan anthem frescoes in the music room—proof that even a house this proud wasn’t immune to Spain’s changing political tides.

Before she died, she established the Amatller Institute of Hispanic Art to ensure it stayed that way. For decades, the house functioned as a research library and quiet academic stronghold. Only in the last 20 years has the house undergone a careful restoration and opened to the public as the museum it is now. The best part? Like that pink marble column, the whole thing exists simply to be admired.

The final stop on the tour is a cup of house-made hot chocolate, rich and spicy and probably very close to what they were serving guests here in 1901. It’s not an add-on. It’s the point. Antoni Amatller built a life—and a home—on the idea that art, design, and marketing could turn something as humble as cacao into an empire.

Next door, Casa Batlló gets the fame. The ticket lines. The TikToks. But Casa Amatller? This one sticks with you. Maybe it’s the silence. Maybe it’s the chocolate. Or more likely both.

Write a comment