I’d seen Fernando Botero’s work before—loads of times. A jolly pope here, a hefty ballerina there. Always charming. Always round. I’d never disliked him, exactly, but I’d also never thought of him as someone who required much from me. Which is why I walked into the Palau Martorell expecting a pleasant afternoon and walked out mildly stunned.

The Palau helps. It’s one of those buildings that doesn’t scream at you from the street but seduces you once you’re inside. Neo-Gothic, late 1800s—all carved stone and stained glass and ceilings that have something to say. They’ve recently restored it and turned it into a temporary exhibition space—rotating shows, no permanent collection. Which is how I found a Botero exhibit there. More than 120 pieces, curated by his daughter and a longtime scholar of his work, arranged not chronologically but thematically, like a personality slowly revealing itself.

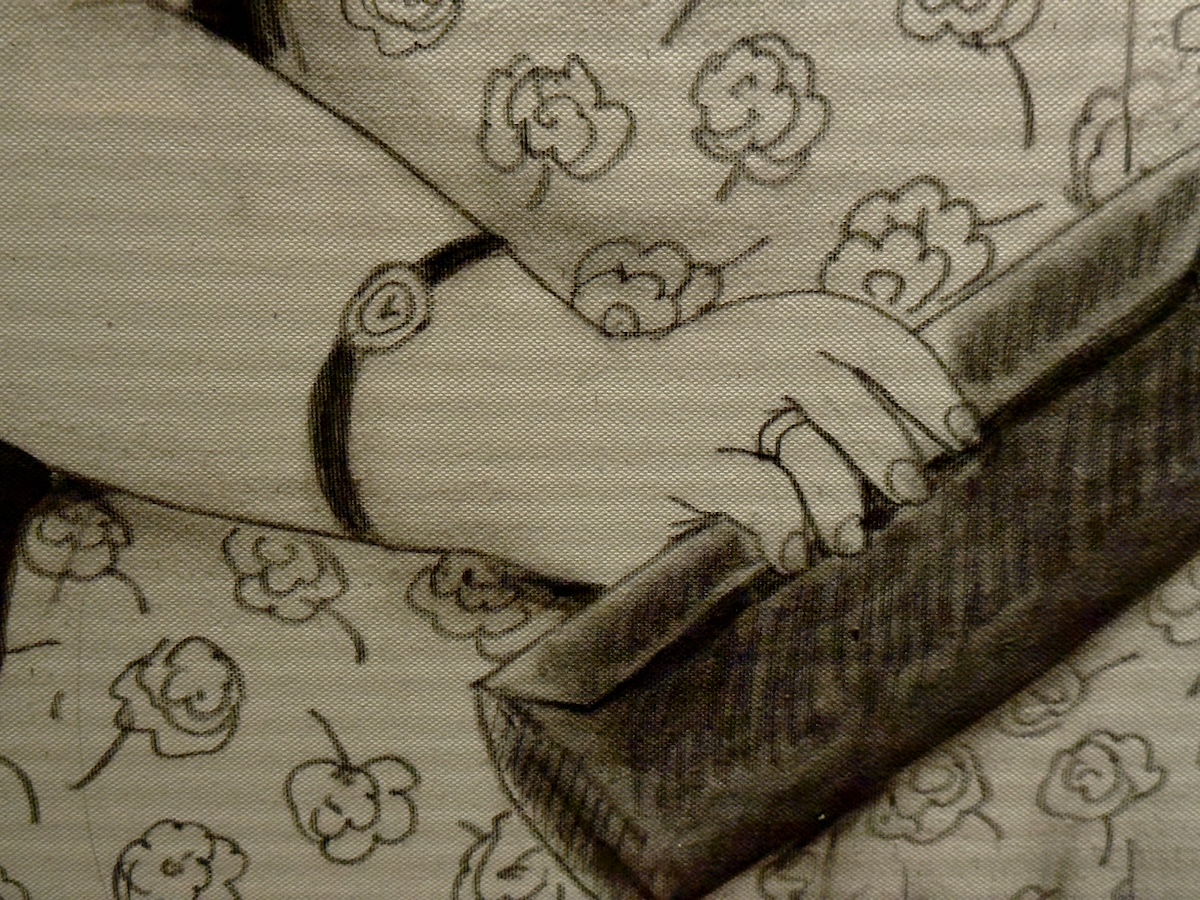

I was surprised almost immediately. Not by the style—that was unmistakable—but by the rigor. Artistic rigor. These weren’t just whimsical exaggerations. They were precise. Controlled. Rooted in a lifetime of technical discipline. And there were so many different media—oil, pastel, chalk, charcoal, bronze. You start noticing the brushwork. The composition. The tension between form and content. And you start realizing that “round” isn’t the point. It’s the delivery mechanism.

One wall held his Flores tríptico—three panels of flowers so dense and saturated they bordered on surreal. Nothing delicate about them. Just color and curve and bloom at full throttle. El Baño was quieter. A woman in repose, all curve and shadow, caught mid-bath. It felt peaceful. But also intrusive. Like we were seeing something we shouldn’t. That was the trick—Botero made stillness feel voyeuristic.

His Homage to Mantegna was a standout. The original—painted in 1958 and lost for decades—takes a Renaissance fresco of the Gonzaga family and filters it through Botero’s proportions. The result is strange and reverent and completely his. Not all of it was reverent. El Presidente y Sus Ministros took aim squarely at power. The suits are bloated, the faces smug, and the self-importance practically oozes off the canvas. You laugh—until you don’t.

Nearby were riffs on Velázquez, Ingres, Raphael—less parody than dialogue. He wasn’t mocking these masters. He was meeting them. On his own terms. In his own shape. His take on Los Arnolfini, after Van Eyck, was less wink than warped mirror—distorted in size, not in seriousness. You’d think it might collapse under its own weight, but it doesn’t. It floats. La Menina, after Velázquez, shows up too—less like a joke and more like an inheritance. He wasn't mocking the Spanish court. He was joining it via volume.

And then it gets heavier.

Botero, who always insisted that art should bring pleasure, made two pointed exceptions. One room was dedicated to his series on Colombian violence—bombings, assassinations, bodies broken by the state. Another focused on the torture at Abu Ghraib.

The forms stayed full, the colors rich, but the impact was anything but soft. You saw bloated figures splayed on interrogation tables. Bruises, blindfolds, silence. There was no sensationalism. Just horror, rendered with unbearable calm. “Art does not have the power to provoke social or political change,” he once said, “but it does have the power to perpetuate the memory of an episode.”

He never sold these paintings. The Colombian works were given to the National Museum in Bogotá, and the Abu Ghraib series went to Berkeley. He called it a matter of principle—you don’t profit from the suffering of others. But what he did do was join the canon of artists who’ve forced us to look. Like Goya’s 3rd of May. Like Picasso’s Guernica. He made violence impossible to ignore by making it—briefly, uncomfortably—beautiful.

By the end, I wasn't sure if I'd just seen a retrospective or been corrected. Botero's style is easy to recognize, but not easy to understand—unless you're willing to stand still, look harder, and let the roundness wear off. I'm glad I finally did.

I took the stairs down. The whole building felt different on the way out.

Write a comment