Visiting the Picasso Museum in Barcelona sounds like a no-brainer. One of the most famous artists in the world, in the city that helped shape him, housed in a string of grand medieval palaces? That’s an easy win.

But here’s the thing. If you go in expecting the angular chaos of Cubism, the rage and grandeur of Guernica, or even the playful surrealism of his later work, you may leave feeling…puzzled. Or in our case, politely underwhelmed.

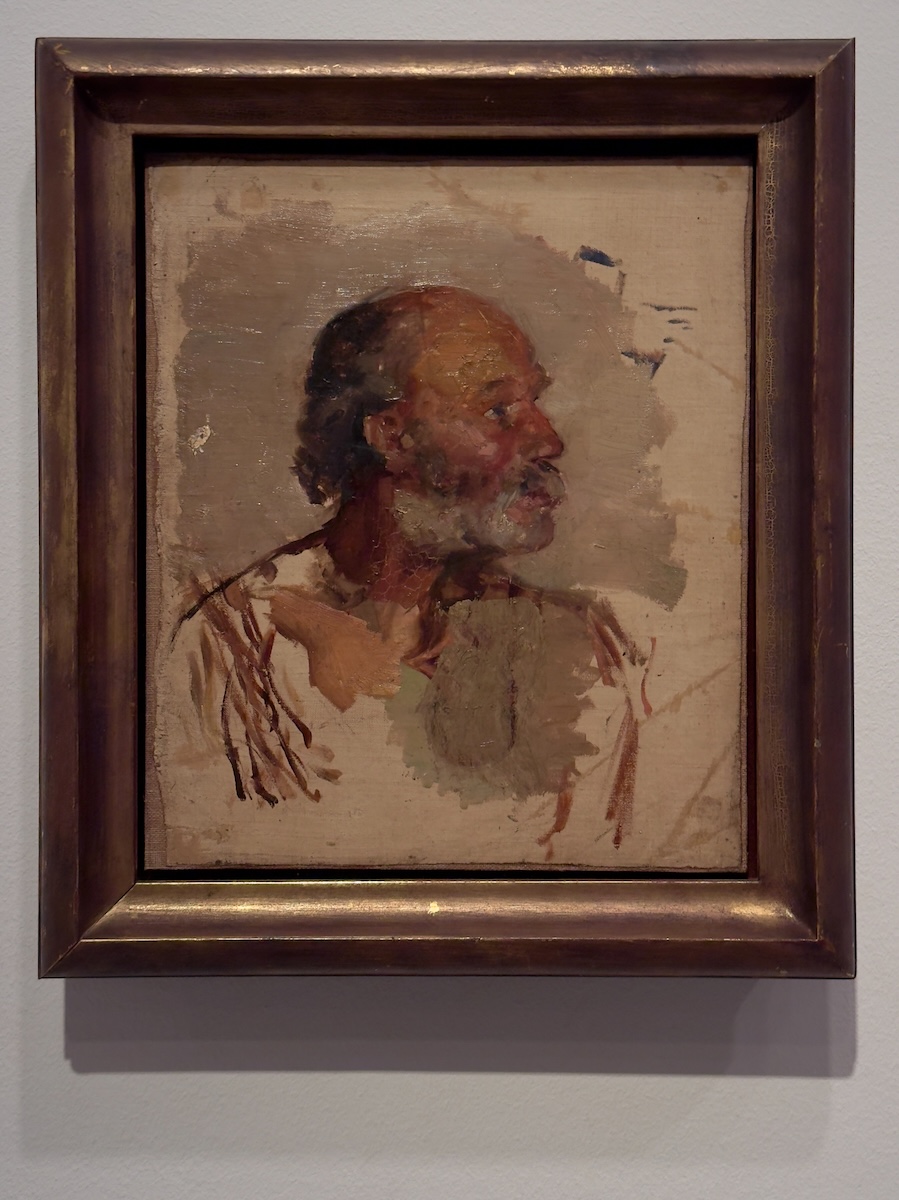

The Museu Picasso is not a greatest-hits collection. It’s a biography in paint—one that lingers in the artist’s formative years. You get prodigious sketches from Picasso, age 9. Oil portraits from his teens. Earnest academic studies that scream “young man desperate to be taken seriously.” One early canvas shows his father in profile, rendered with quiet skill and absolute control—and absolutely nothing else. It’s technically flawless. Emotionally? Like a homework assignment he knew he’d ace.

It’s like attending a Green Day concert and the setlist is their best demo tapes. Though that might appeal to some (looking at you, Dezsi!).

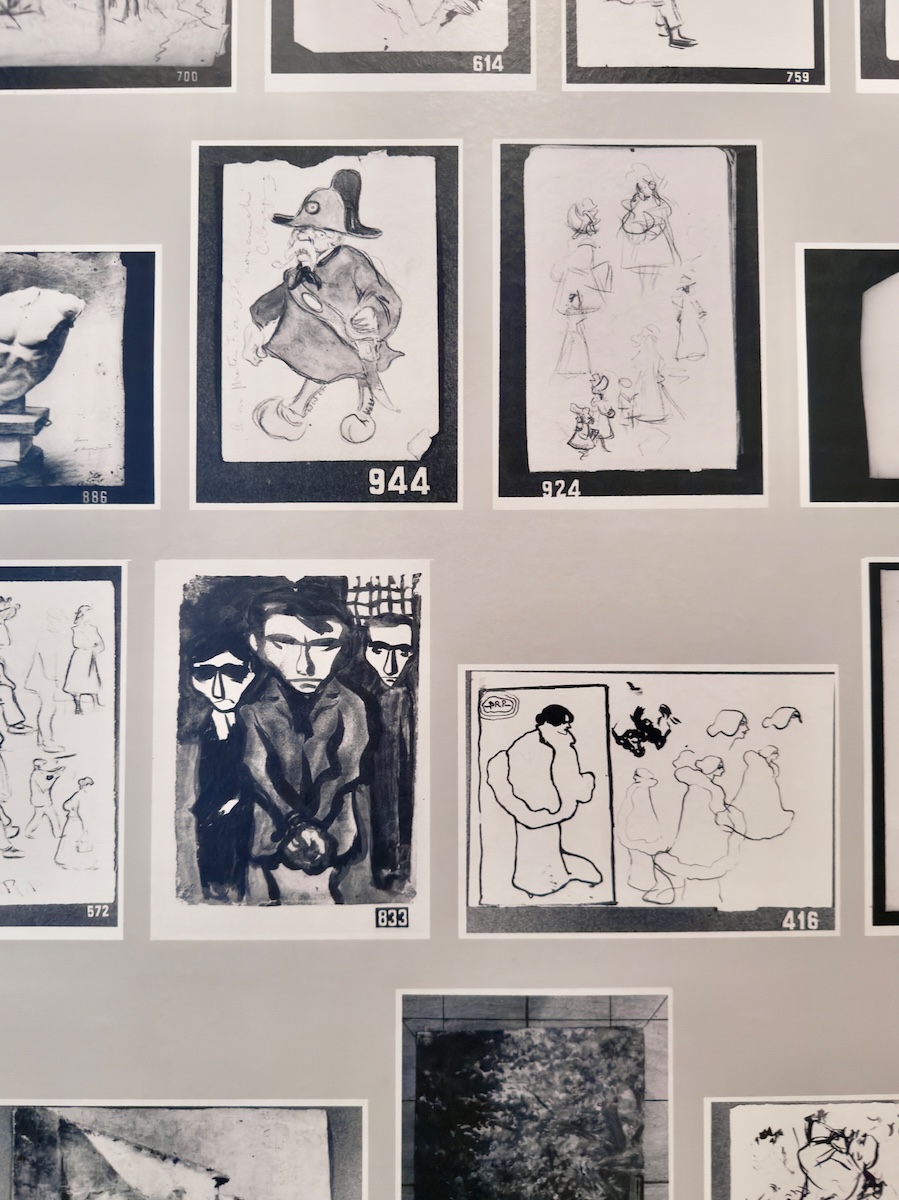

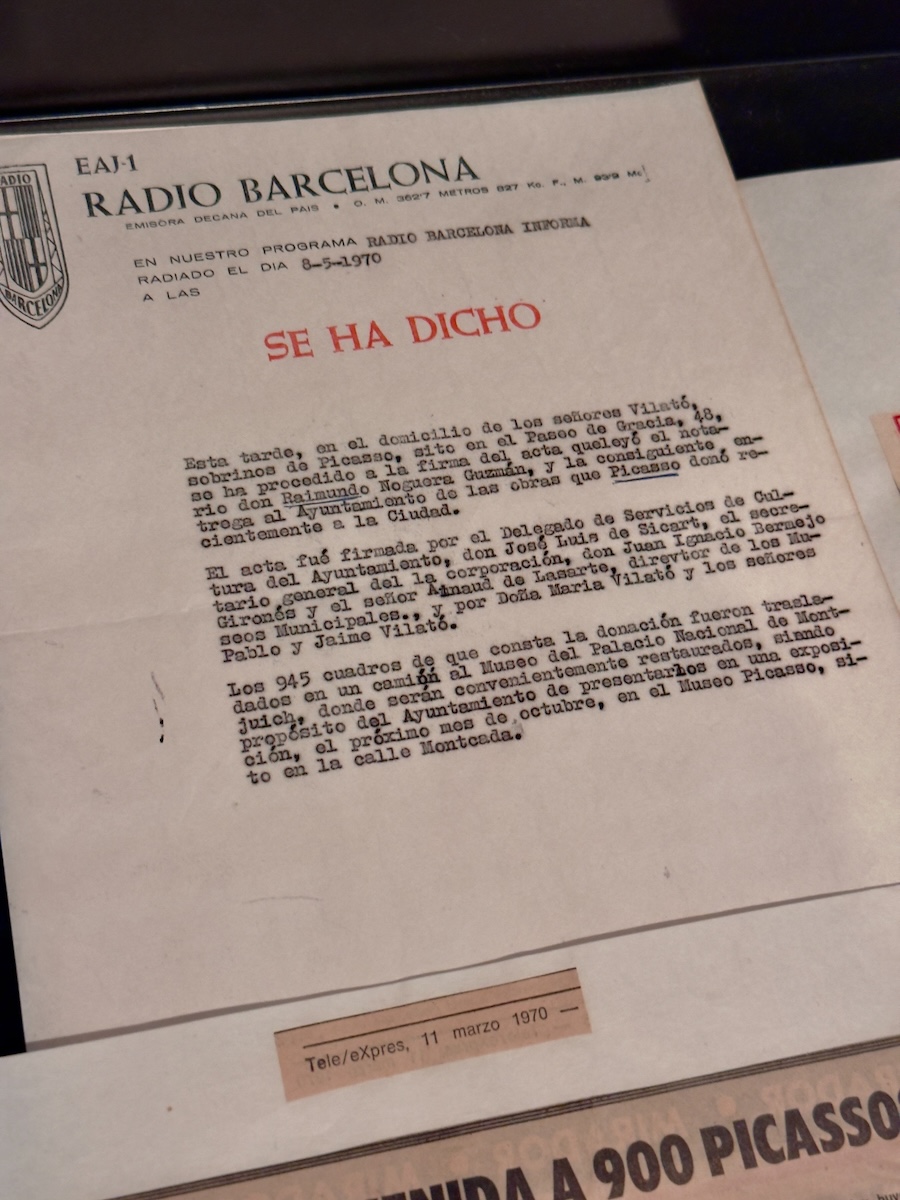

That’s not a dig on the museum. If anything, it’s true to its mission. In 1970, Picasso formally donated over 900 early works to the city of Barcelona, in honor of his lifelong friend Jaume Sabartés. Most of the pieces had never left Spain. They'd been stored for decades in the family home, handed down from his parents to his sister Lola, and eventually to his niece and nephews. It was his niece, María Dolores Vilató Ruiz-Picasso, who ended up having to sort through it all after Lola's death and photograph everything for her uncle in France.

Sidenote—Rick and I couldn’t help relating. We’d just spent months back in Oregon helping deal with his parents’ house and collections, decades of artworks, journals, postcards, books, and photos. It’s a strange, emotional thing, trying to impose order on someone else’s creative chaos. You’re constantly toggling between deep respect, mild confusion, and a ruthless need to just get through it. My point? María Dolores deserves a medal. And probably a stiff drink and a long nap. We feel you, María. If we’d been in charge, half the museum would be labeled “Untitled, Possibly Important?”

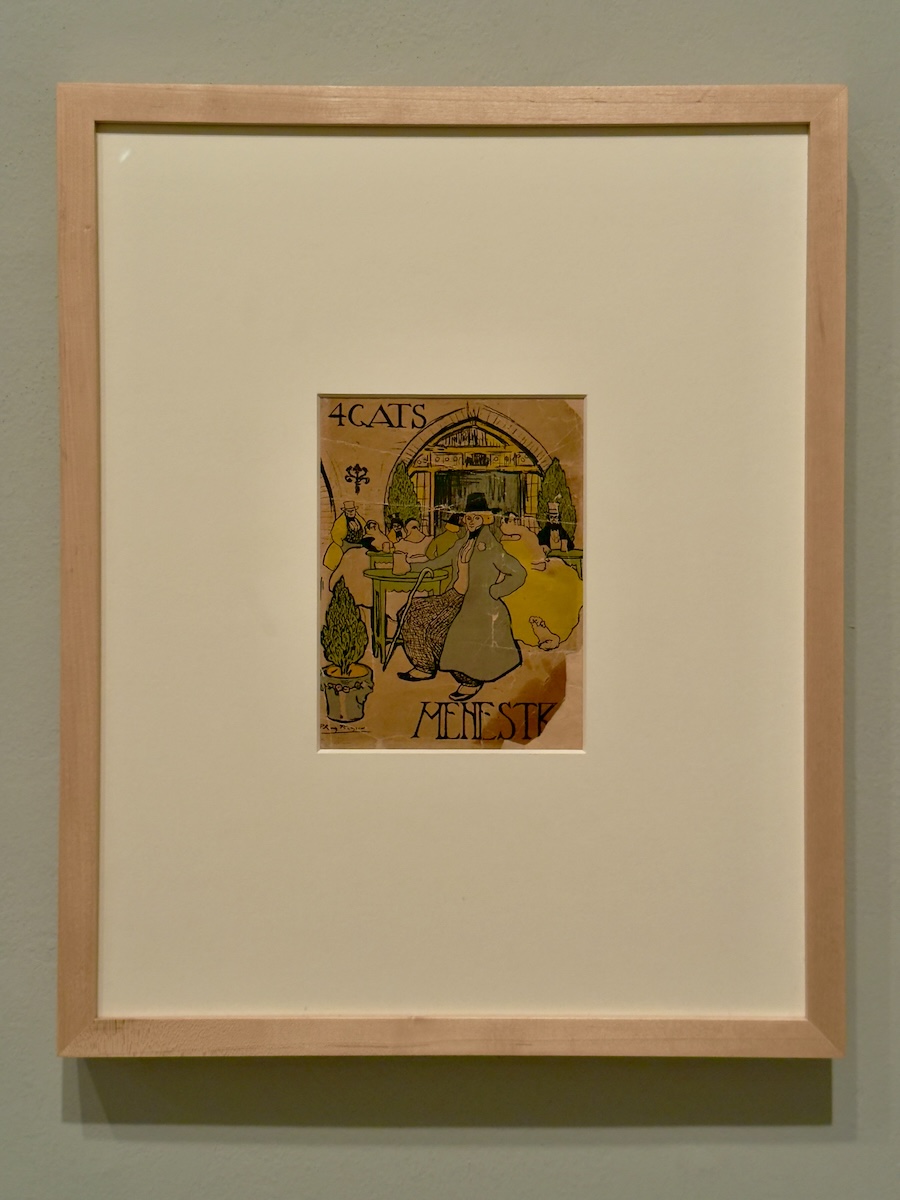

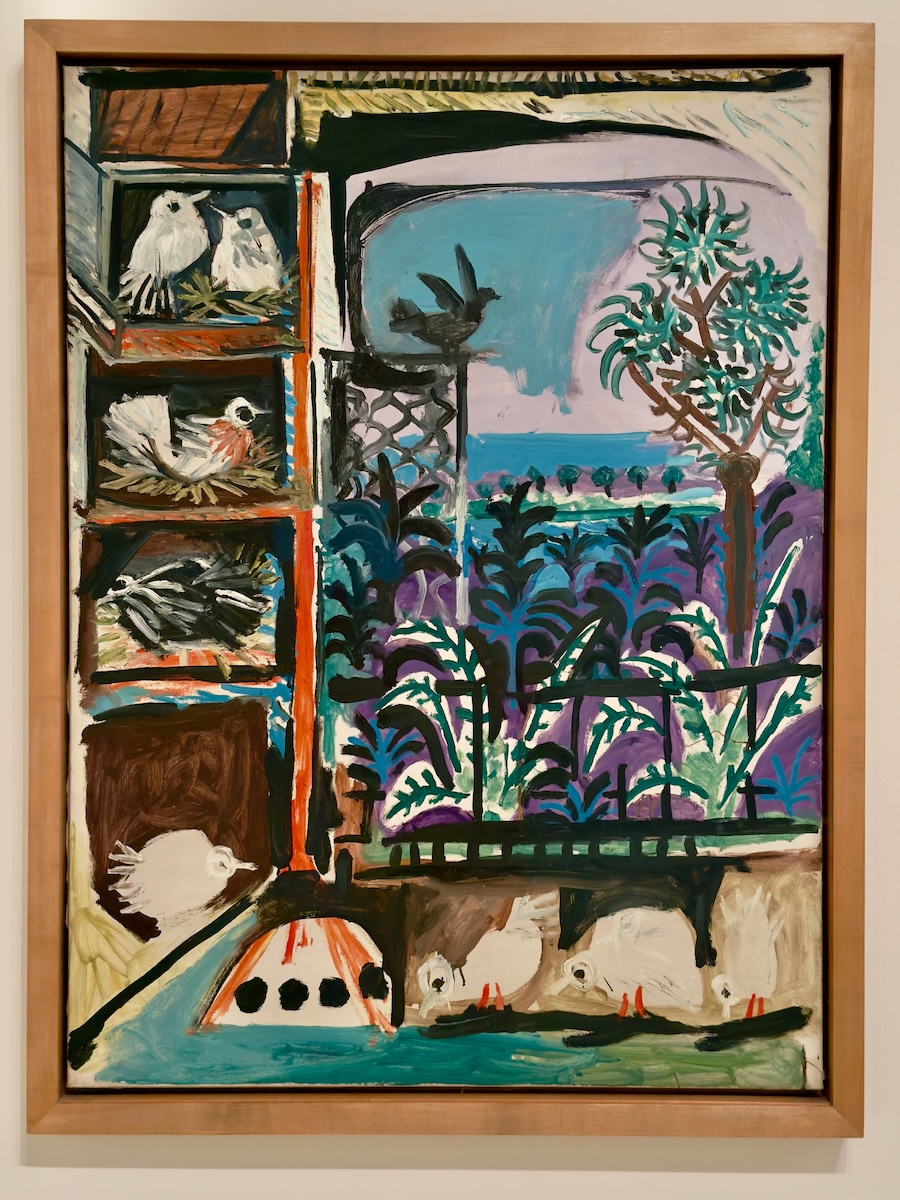

But personal attachments can become institutional history. All that emotional archaeology—the cataloging, the choosing, the letting go—ultimately shaped what we see today. The collection that resulted from all that sorting is what defines this museum. A few iconic works anchor the later rooms—pieces from his Blue Period, and the full 1957 Las Meninas series in all its obsessive brilliance—but the bulk of what you'll see are the early pieces. It's a portrait of the artist, not yet a young man, still apprenticing, still mimicking, still looking for his way out.

It’s also, in some ways, a portrait of Sabartés. Most museumgoers won’t recognize the name, but his influence is everywhere here. He met Picasso in Barcelona in 1899, when they were both just starting out, and they remained close for life. Sabartés became Picasso’s secretary and literary executor, managing not just logistics but reputation. It was Sabartés who helped open the original museum in 1963, and Sabartés whose name it initially bore. Picasso didn’t even want his own name on the façade until much later. It was never about ego for him—at least not in this instance. It was about honoring the friend who’d stood by him through everything.

And maybe that’s why the building itself matters so much. The museum is housed in five adjoining palaces—de Aguilar, Baró de Castellet, Meca, Mauri, and Finestres—each one a centuries-old stunner. Vaulted courtyards. Carved stone staircases. Gothic windows that look like they were built specifically for Shakespearean monologues. It’s an architectural collage, full of quiet corners and unexpected symmetry. If you’re not feeling it with the art, just look up. You’ll be stunned.

The whole thing feels intimate, even a bit secretive. No blockbuster exhibitions, no big-ticket gift shop pushing beach towels printed with The Weeping Woman. Just a deeply personal archive, in a beautifully complex building, in a city that Picasso always considered home, even after Paris claimed him for good.

Would I recommend it? Sure, if you're a completist. But if you're short on time, maybe not so much. It was worth it for us, mostly for the quiet truth of it and the reminder that genius rarely comes fully formed.

Sometimes it starts with a pencil sketch, tucked in a drawer, waiting to be found.

Write a comment