How much do you know about Ponce de León? Did you know his first name isn’t even Ponce? That he was the first governor of Puerto Rico—but only for two years before getting thrown over by the king in favor of Columbus’s kid? That his (in)famous Fountain of Youth expedition came after he lost the job, like some mid-life pivot or pride project?

Yeah, me neither. Mostly, he lived in my brain as a cartoon conquistador with a big hat and a bad map.

But I learned so much more about him at his house in Old San Juan. A house he never actually lived in. Classic Ponce.

There's a lot more to the man—most of it predictable and none of it particularly noble. Juan1 Ponce de León was born around 1474 in Spain2 to a family of minor nobility. The kind of nobility that gets you a spot polishing real noblemen’s boots. After shining boots and fetching goblets for a few years, he joined Christopher Columbus3 on his second voyage to the New World in 1493 as a “gentleman volunteer.” Vague.

After arriving in the Caribbean with Columbus, he earned favor by helping to mercilessly crush local resistance in Hispaniola4—and was promoted for, well, being so good at it. He’d caught the Crown’s roving eye, and in 1508, they awarded him a royal contract to explore and settle Puerto Rico. Which he did. With a vengeance. By 1509, he'd crushed the local Taíno people, carved up the island for plantations and settlements, and founded Caparra—the first Spanish settlement in Puerto Rico, not far from modern-day Guaynabo.

As a result of his diligent efforts, he was crowned appointed the island's first governor by the king, but over the bitter objections of his enemies .5 Chief among them was Diego Colón, the son of an even more famous genocidaire. Colón is the Spanish version of Columbus, and Diego had inherited his father Christoper’s6 legal claim to govern all of the West Indies. The world’s original nepo baby? Probably not. But for the sake of this story, sure.

King Ferdinand sided with Diego in 1511, unceremoniously booting ol’ Poncy from the job he’d just settled into.

Don’t feel bad, though. Ol’ Poncy kept all his land, wealth, fancy armor, and—to a certain extent—royal favor. The king knew better than to piss off a loyal soldier with a sword and no direction. So in 1512, Ponce was awarded a consolation prize—exclusive rights to explore lands north of Hispaniola. That means Florida, people.

He set off in 1513, claimed the peninsula for Spain, despite the locals’ misgivings ,7 and then went back in 1521 to start an actual colony. That’s when things took a hard turn. The Calusa people had decided that a flag wasn’t all that, and they, um, declined his self-issued invitation to their home. He was shot by a poisoned arrow during an indigenous attack and limped back to Cuba to die.

So by the time his son-in-law broke ground on this house, Casa Blanca, ol’ Poncy was long out of office, mid-flop in Florida, and bleeding fatally from a poor decision. But, you know, he kept the title “First Governor of Puerto Rico” the way people keep honorary doctorates—loudly and forever.

Even though he was dead dead dead, his family back in Puerto Rico was living large on land granted by the Spanish Crown and dutifully started construction on a fine wooden house at the edge of the newly relocated city of San Juan. It promptly burned down. So they built it again—this time with rubble and stone, as if to say, “Dad’s gone, but the family brand is strong.”8

And that was just the beginning. Over the next 400 years, Casa Blanca would be expanded, reinforced, subdivided, militarized, gutted, gardened, and turned into a gallery—10 distinct architectural phases in all.9 It started as a cube-shaped adobe house in 1521 and then refused to die. By the time the Dutch attacked San Juan in 1625, it had sprouted bastions and towers. Then came officer quarters. A kitchen. A second floor. A gallery. A fountain, courtesy of a U.S. colonel with lofty landscaping ambitions.10

I’d tried to visit a few days earlier and spent a full hour sweating through Old San Juan trying to locate the entrance. I finally found the front gate by tailing a hotel maid up a service staircase like I was crashing a wedding. Closed. Turns out it’s only open Wednesday through Sunday. And only for two specific three-hour windows, 8–11 and 1–4. Like it was some sort of colonial pop-up speakeasy.

When Krista and I finally did step inside, it was just us. There was a guy took our money, but no guards, docents, or other visitors. Just the echo of our sandals and the slow realization that the displays, while earnest, were almost entirely unlabeled. The only real context came from a handful of oversized wall posters—surprisingly well-translated into English but clearly selling an agenda.

You wander through spare bedrooms and utilitarian kitchens, with their swinging pots and lead-heavy jugs, and you realize that maybe being part of the colonial elite wasn't exactly a spa vacation. Even the wooden pew in the private altar room looked punishing. If this was power, it came with chores.

Outside, the gardens are lush and perfectly imperfect—added, of course, by a U.S. Army colonel in 1939, when the house became the official residence of the American commander in Puerto Rico. That’s right—after two centuries as a family home, Casa Blanca spent nearly as long as a military installation, first Spanish, then American. The trapdoor? Possibly for wine. Possibly for weapons. Definitely not for anything good.

Casa Blanca became a museum in the 1970s. And it shows—there's a slight mid-century stiffness to the displays as if they were arranged by someone who respected history but didn't quite trust you to touch it. Which is fine. This place isn't really about one man, anyway.

The house goes to great lengths to honor Ponce de León as the First Governor of Puerto Rico. But very little is said about how briefly he held the job. Or how brutally he earned it. Or that he died not exploring Puerto Rico but by bleeding out in Cuba after trying to claim land from people who very much didn’t want him there.11

There's plenty of tribute to the family name and almost nothing about the people who lived here before it became real estate. The Taíno get a passing mention. The Calusa, who likely ended Ponce's career in both the metaphorical and literal sense, aren't mentioned at all. You'll see Spanish swords and Flemish tiles, but nothing of the Indigenous cultures erased to make room for them. It's a house built on conquest that now functions as heritage. And, like a lot of historical sites, it's more comfortable memorializing architecture than accountability.

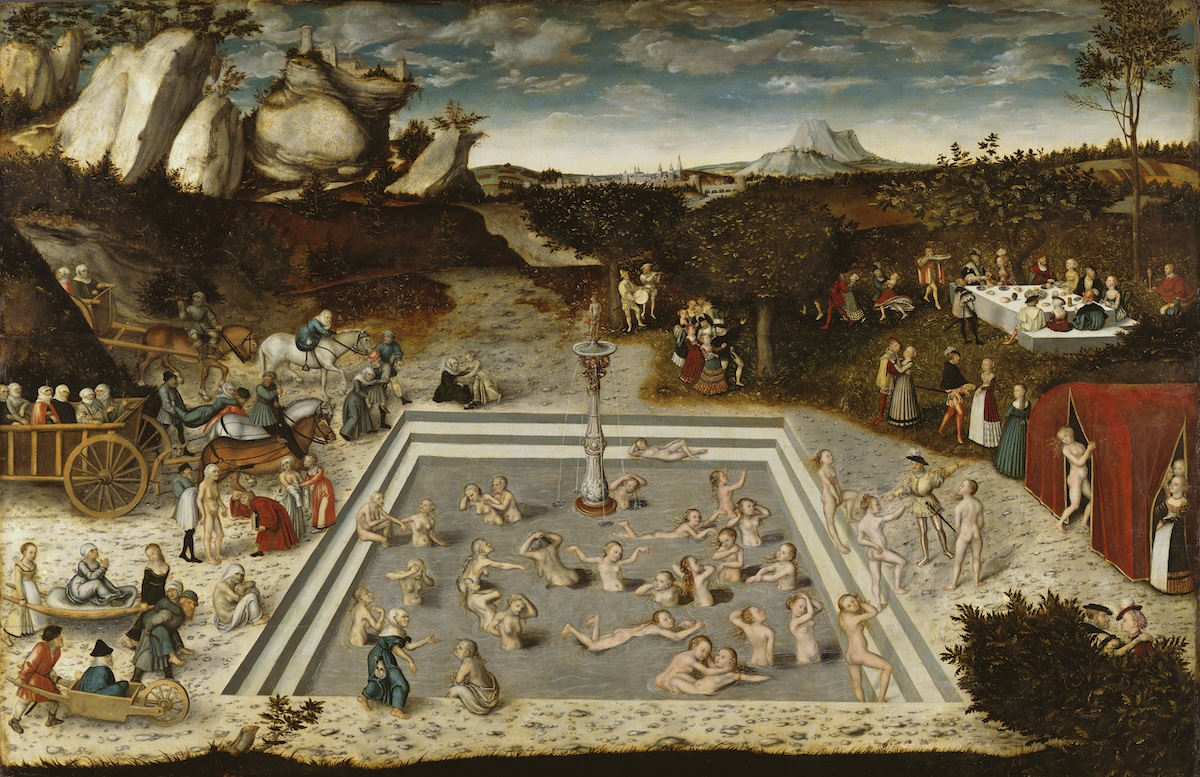

Ponce de León never did find the Fountain of Youth, but probably because he wasn’t even really looking for it—at least not officially. That part of the story was bolted on by chroniclers decades later. He was looking for land, resources, and a shot at reclaiming royal favor after being muscled out of Puerto Rico’s top job by a better-connected rival. What he got was a poisoned arrow and a questionable legacy.

But the myth endured. It gave Florida a founding fairytale, justified a century of health, wellness, and magical water marketing, and allowed one of Spain’s lesser colonizers to graduate into pop culture sainthood. His name is on parks, highways, high schools, and cruise itineraries. All for chasing something he never found and probably didn’t believe in to begin with.12

Casa Blanca isn’t about Ponce de León. Not really. It’s about what survives. The myth survives. The title survives. The stone survives. The architecture survives—even if it’s been Frankensteined together like a colonial patchwork quilt. What doesn’t survive is context. Or contradiction. Or the names of the people who were here first.

And yet, walking through it—with its pews, jugs, and shadowed corners—you get a sense of how long power can linger in a place. Not just power but the performance of power. The kind that wears armor in the tropics. The kind that carves fountains into conquest. The kind that turns a governor's footnote into a headliner.

History, after all, isn’t just what happened. It’s what we keep showing up for.

Write a comment