There are three faces to Mérida— one carved in stone, one kept in memory, and one still playing out in the streets. And all three versions layer neatly on top of each other, like architectural sediment.

The current one, best seen through a sun-washed Instagram filter, is bright, clean, and pleasantly choreographed. Musicians on the plaza. Free folkloric performances every night of the week. Horse-drawn carriages waiting patiently for their next sweaty pair of newlyweds. It’s theatrical and self-aware and a teensy bit smug—but endearingly so, like someone who’s been told by every travel magazine in the hemisphere that they’re charming and has finally started to believe it.

The second Mérida—the one people remember, or claim to—was a Belle Époque boomtown funded by henequén, the so-called “green gold” of the Yucatán. You know, the plant the Maya had been using for centuries before the Spanish “discovered” it. In the late 1800s, that fiber made Mérida briefly richer than Mexico City. The city responded by building mansions with more wrought iron and architectural flourishes than a Paris opera house. They also installed the country’s first streetlights, cable cars, and indoor plumbing—all decades before anyone figured out how to pave a decent road to get there.

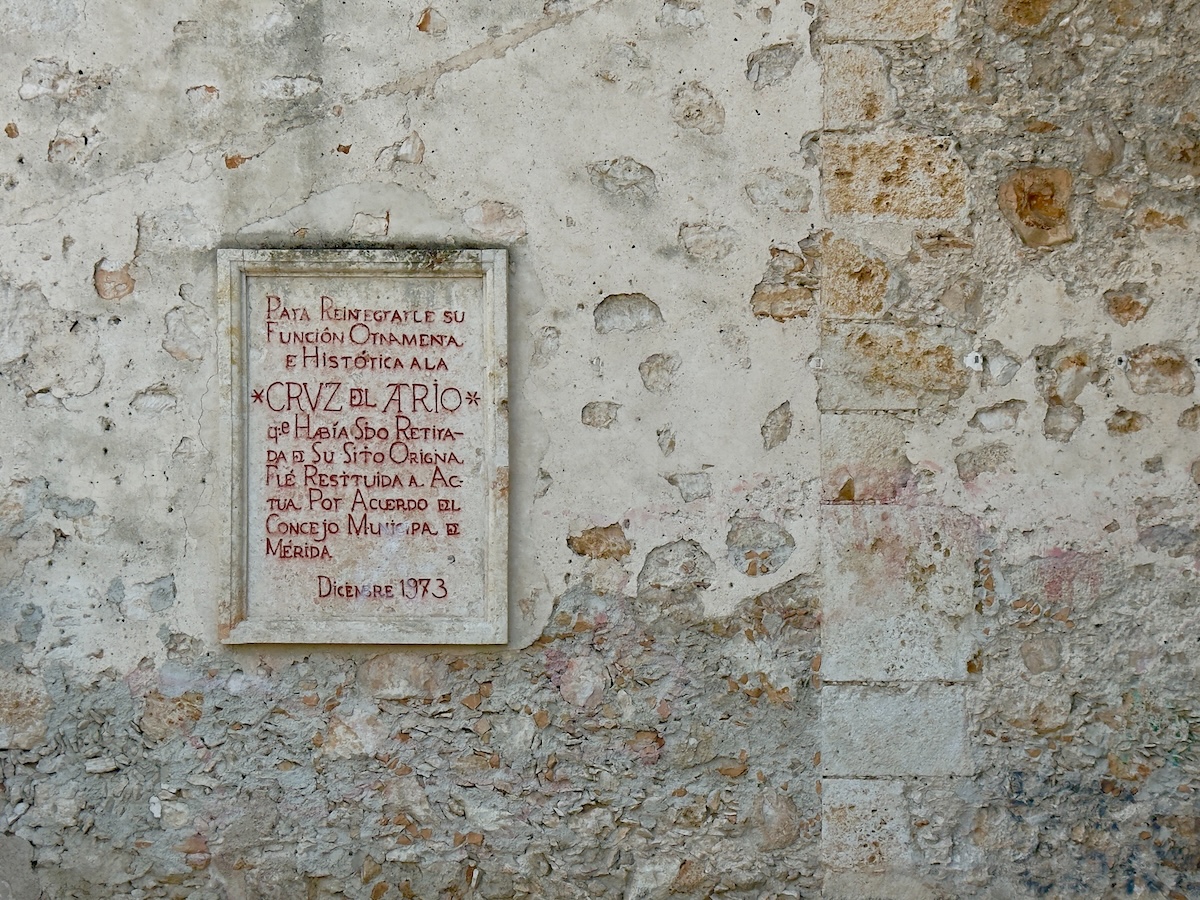

But the first Mérida was built by the Maya—and then dismantled, renamed, and rebuilt by the Spanish. By the time Francisco de Montejo showed up, the Maya city of T'Hó was already mostly in ruins, its pyramids crumbling and its people living in straw huts. It made the perfect blank slate for a colonial capital. Montejo claimed it—on orders from the Spanish crown and over the fierce objections of the people already living there. He was sent to conquer the Yucatán, and this ruined city was geographically convenient for establishing control. His men built the Plaza Grande right over the old temples, with a cathedral to the east, his own massive mansion to the south, and a government palace to the north. He rounded it out with an "Imperial Palace" to the west, which sounds impressive until you realize it wasn't home to any actual emperors—just more Spanish bureaucracy.

Despite all that pomp and money, Mérida spent most of its life forgotten by the rest of Mexico. For the longest time, there were no roads, no rail, no hurry. It’s part of why the city still feels so distinct from what Meridanos sometimes call el interior—Mexico as viewed from the capital. People here speak both Spanish and Maya. The pace is slower. Even the food is different, thanks to deep Maya roots, geographic isolation, and Caribbean influences—less tacos-and-salsa, more achiote, sour orange, and cochinita for breakfast.

There's a genteel stubbornness about the place—like it's been ignoring central authority since 1542 and sees no reason to stop now. Which is probably why we liked it so much. We spent several weeks here—until our stay was cut short—mostly sweating. The city is flat and sun-bleached, and every afternoon, it felt like someone had draped a wet wool blanket over the entire peninsula. But somehow, the heat made the city feel more alive—like everyone was moving at a careful simmer, conserving their energy for a good reason. That reason often turned out to be tacos.

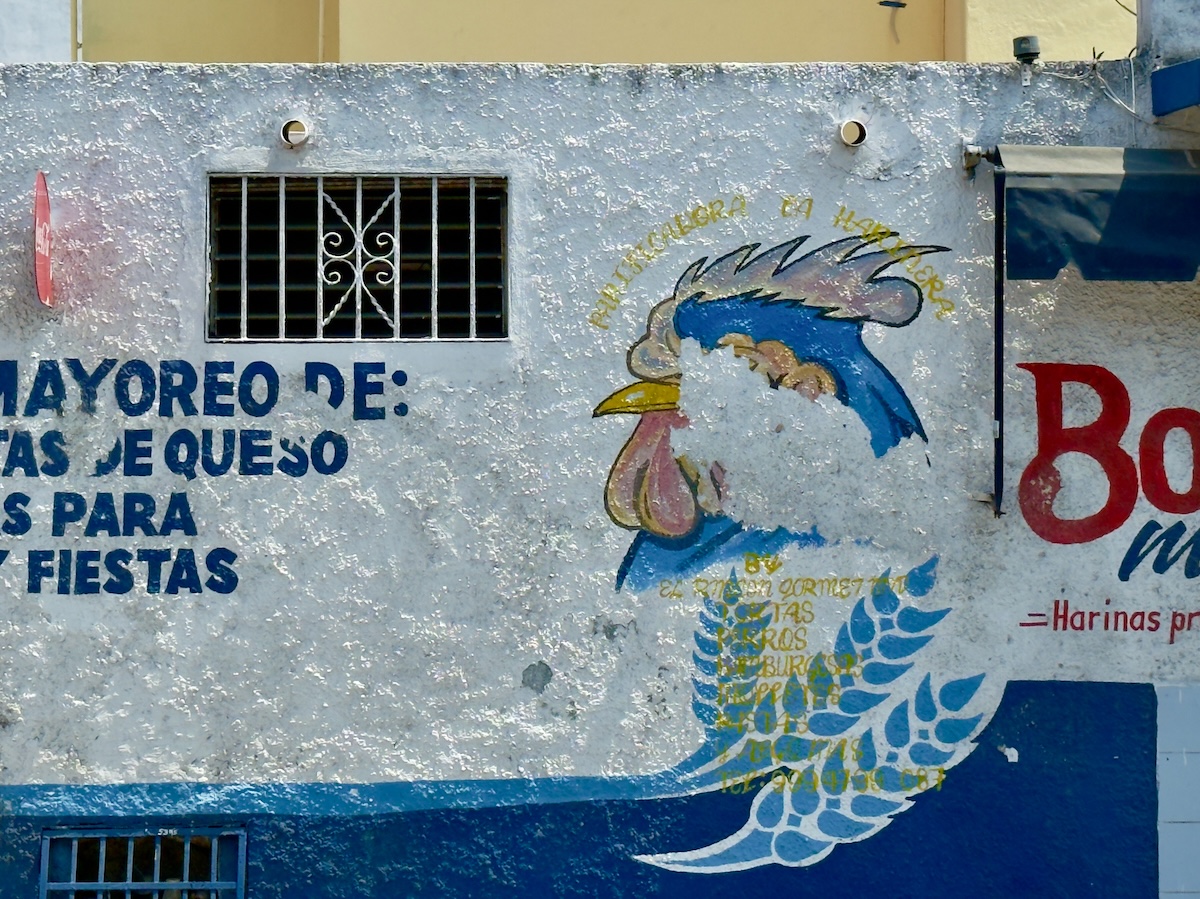

Mérida’s real magic, though, isn’t in its past or its performance. It’s in the lived-in moments—fruit sellers shouting under faded awnings, school kids in matching uniforms playing in the shade of churches built from the rubble of Maya temples, neighbors chatting through open windows as parrots scream overhead. It’s in the way the streets still follow the old colonial grid even as the city grows in every direction, spilling outward like lava from a volcano that forgot to explode.

You don’t come to Mérida to be dazzled. You come to see what it looks like when a city reinvents itself for the third time—and decides to enjoy it this time around.

Write a comment