When I first discovered El Gallito, we were lost. Again.

Not just metaphorically. We were physically, embarrassingly, should-we-just-turn-around lost. And this, as it turns out, was the ideal condition for spotting Mérida’s esquinas—those curious, tile-labeled intersections with names like La Casita Azul, La Teja, and El Huech (which is not the sound a Mexican sneeze makes, in fact, but Maya for armadillo).

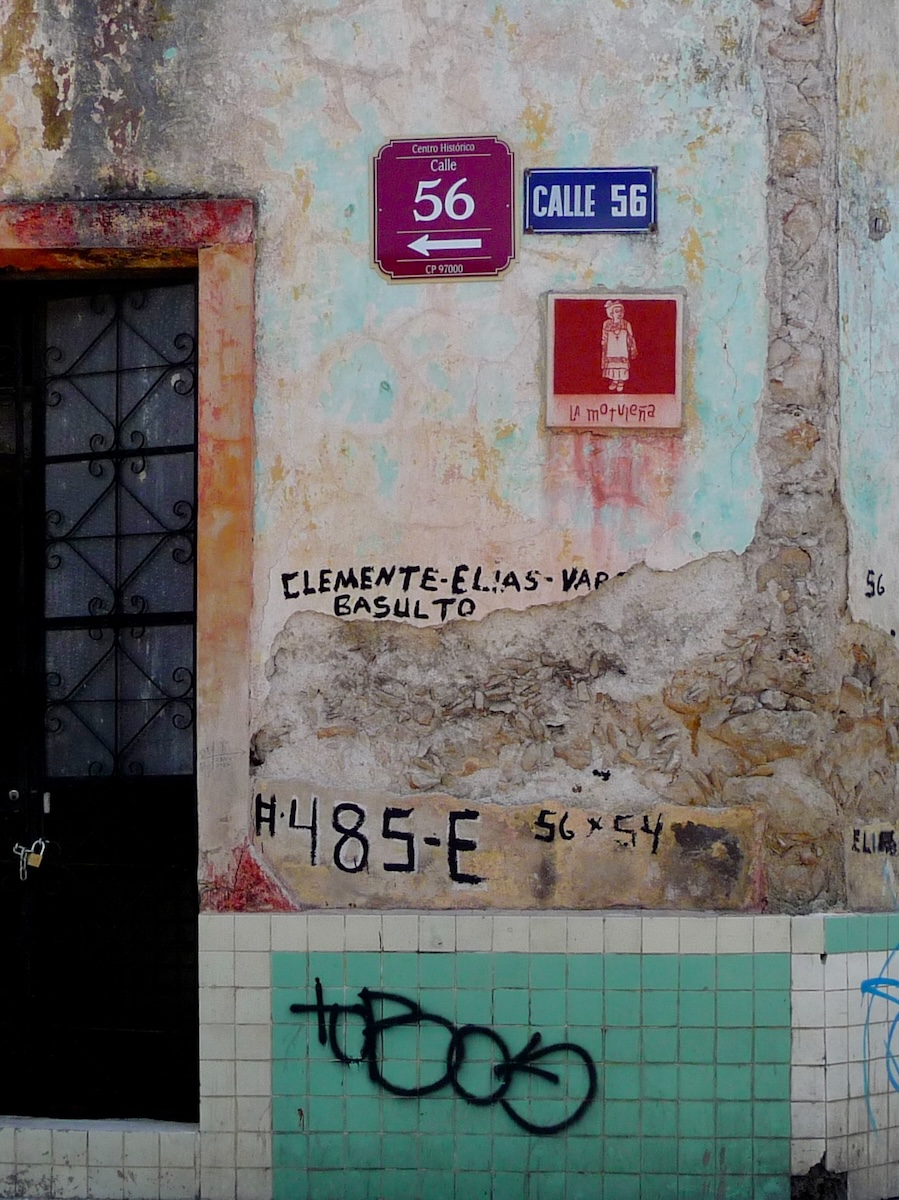

If you’ve only seen a map of Mérida, you’d be forgiven for thinking it’s impossible to get lost. The street grid looks like an OCD dream—perfectly straight and numbered—but it's a trap. Even-numbered streets run north-south, odd-numbered ones run east-west, and the numbering system starts from a seemingly arbitrary point in the city's northeast corner. Not, as you might assume, at the grand Plaza Grande in the historic center. Because that would be helpful.

Which is why we eventually stopped trying to navigate and started chasing corners instead.

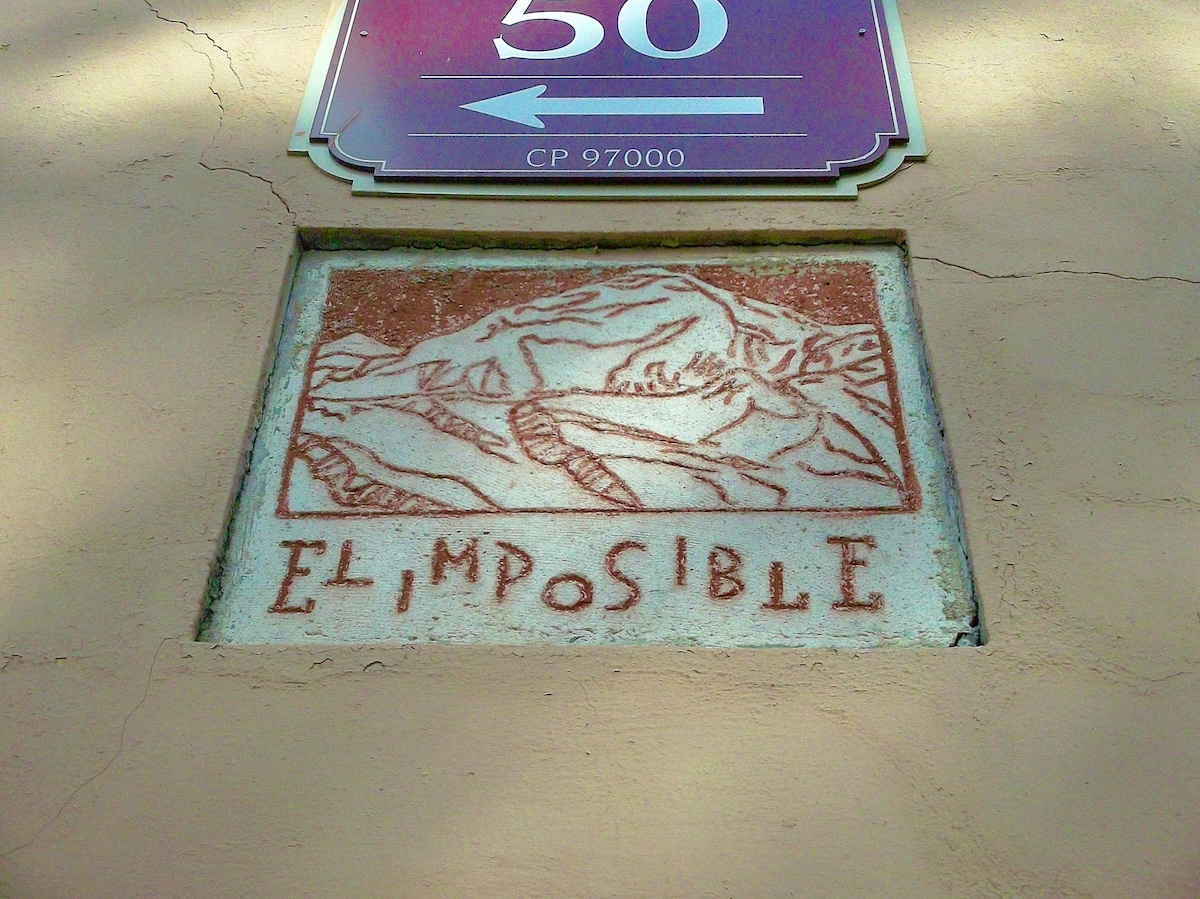

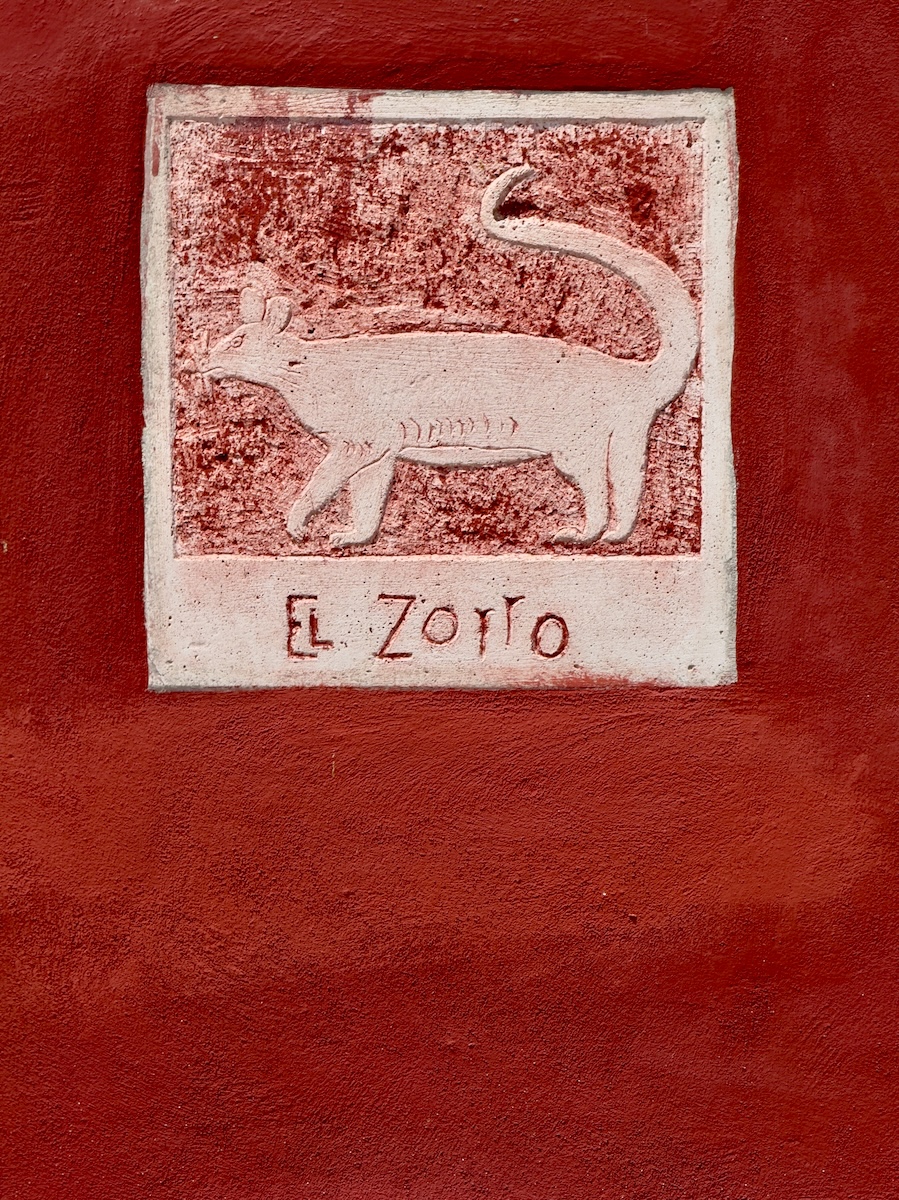

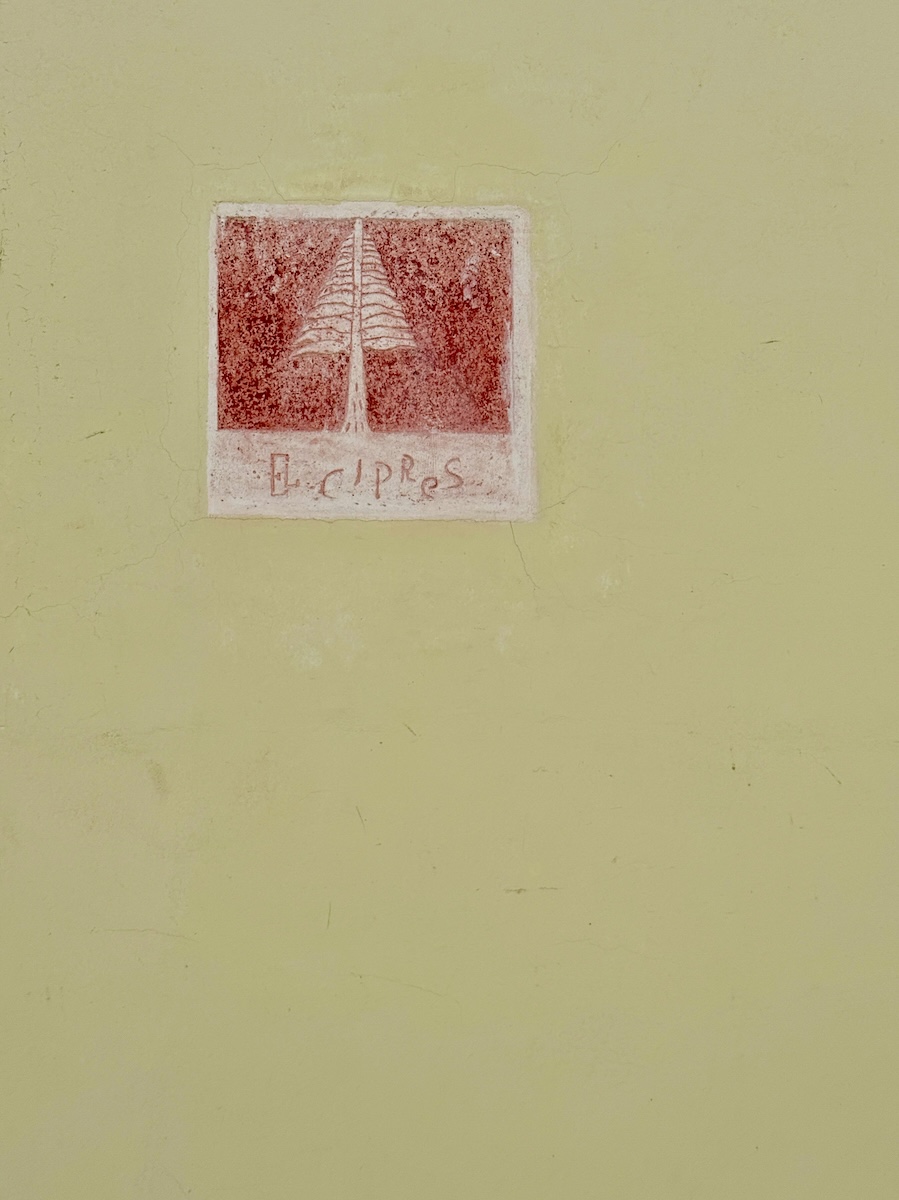

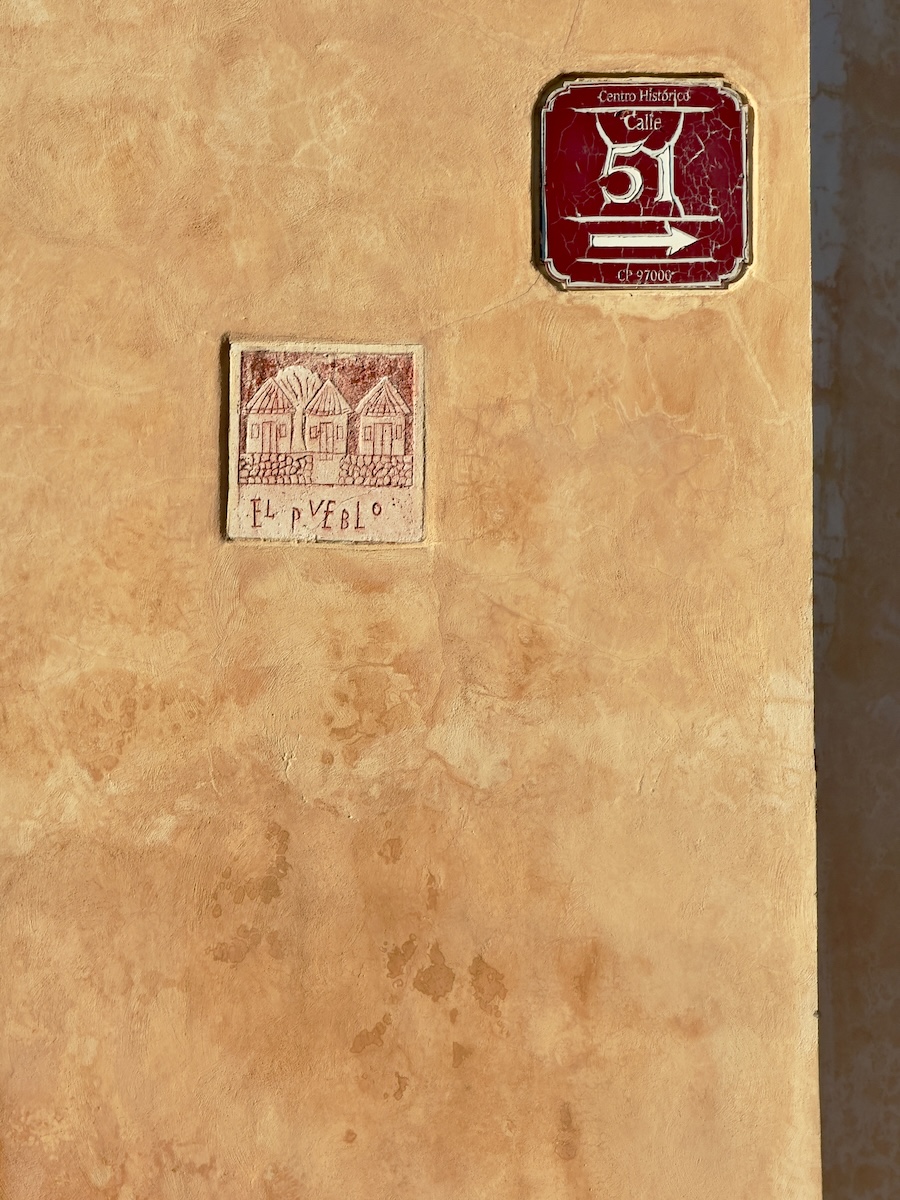

Mérida’s esquinas are named intersections—literally building corners—each bearing a nickname, usually on a red-and-white plaque with a charming pictogram. Some names are odd, and some are oddly specific. And together, they form a kind of alternative city map—a network of stories, jokes, superstitions, and the occasional public tragedy memorialized in stucco.

For most of Mérida's colonial history, there were no street names. No numbers. No signs. You got around by reference—"the place with the tamarind tree" or "the house where that guy got stabbed." Corners became landmarks, and landmarks got nicknames. If enough people used one, it stuck. Stories accumulated. Thus, you find El Ciprés, where a cypress tree, El Chévere named for a stylish little shop, and another called La Duquesita for a woman with a serious attitude.

In 1890, the postal service finally threw up its hands. Town was getting big, and it was becoming harder and harder to deliver mail to “Bob near the corner with the elephant statue.” Street numbers were introduced by royal decree, and the esquinas became officially unofficial, relics of an oral tradition that refused to die. Which was lucky, because anyone who couldn’t reliably remember “Calle 61 x 54”—the very young, the very old, the hungover—could still remember to meet at El Tigre.

Most of the names stuck. A few disappeared and came back. Others were replaced by something more contemporary, like El Autogiro (The Helicopter). The city eventually made the system semi-official again and began installing permanent placas—mixing replicas signs with the old ones still hanging on like family secrets.

Once I discovered them, I spent many, many afternoons traipsing around “collecting corners.” There’s El Elefante, named for the metal elephant someone once hoisted onto their rooftop terrace. La Teja, named, I assume, for a roof tile. Los Moscovitas, the Muscovites, which I’m still not entirely sure how to explain. La Puesta del Sol might have the most poetic name of all, though it’s not all that practical unless you happen to be there right at the actual sunset. Otherwise, as everywhere in Mérida, it’s just…sunny.

We didn’t use the esquinas to navigate. We were always off by a block or three, anyway. But the plaques gave me something better than directions—mystery. Like a citywide treasure hunt. Each one was a story fragment, a marker of memory. Like El Degollado, the “cutthroat” corner, named for a barber who took his own life after the object of his affection chose to marry the governor instead. Her esquina? Just a block away, La Veleta—the fickle one. You couldn’t write better symbolism if you tried.

Some corners still mark functioning businesses. Others sit quietly above hardware stores, bus stops, or cracked pastel walls. A few plaques are pristine, but many are sun-faded to near indecipherability.

We left Mérida with no working sense of direction but a deep affection for its street corners. We couldn’t tell you which calle connects to what anymore—but we could take you straight to the little blue house, the armadillo, and the rooster with attitude.

And honestly, isn’t that the better map?

Write a comment