We intended to go back.

It was late when we wandered into the cathedral. The lights were already dimming, the crowd thinning, and our plan was to return later in the week—maybe catch a morning mass and definitely get better photos. But the week didn’t cooperate, and we left Mérida with only the shots we had.

Still, what we got was unforgettable.

Mérida’s cathedral is dedicated to San Ildefonso, who—if you haven’t brushed up on your Visigoth bishops lately—was the 7th-century Archbishop of Toledo and one of medieval Spain's fiercest defenders of the Virgin Mary's perpetual virginity. Legend has it she appeared to him in person and handed him a heavenly chasuble as a thank-you for his devotion. The Spanish have long considered him a symbol of doctrinal purity and divine favor, which makes sense if you're building your first cathedral in the New World and hoping to impress God and the neighbors.

And the Catedral de San Ildefonso doesn’t do subtle. It’s the oldest cathedral on the American mainland, built between 1561 and 1598 on top of what was once the Maya city of T’Hó, using stones pilfered directly from its temples. Twin towers in Moorish style, Renaissance bones, and a plain stone face so stern it makes you feel like you’ve already disappointed your ancestors.

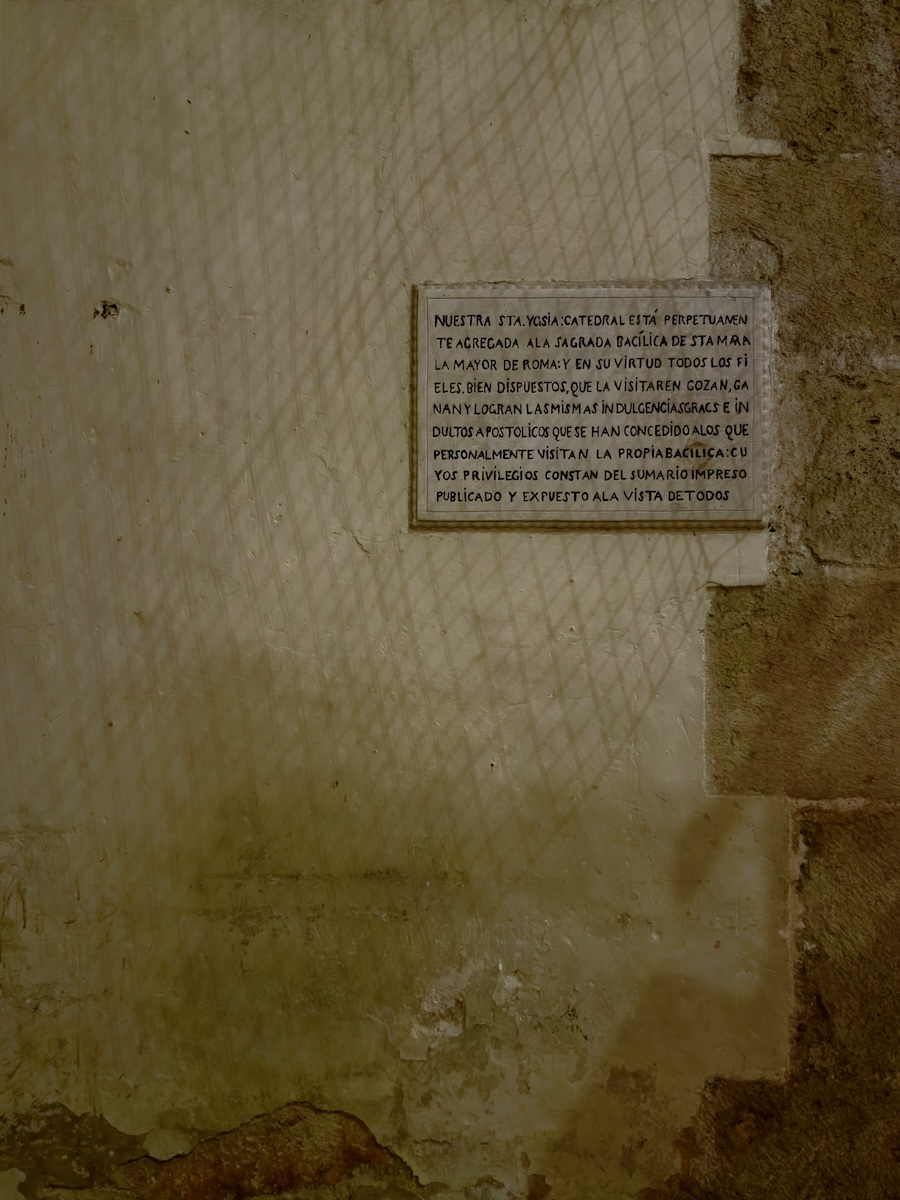

The inside is even more austere—no frescoes, gold leaf, or overachieving cherubs. Once, there was more, so much more. Most of the decorations were ripped out during General Alvarado's anticlerical campaign during the Revolution, and no one has rushed to re-bedazzle the place since. What remains feels spare but intentional, like the building is making a point.

This cathedral has stories, and some apparently still walk around. Some say the ghost of a flayed Spanish soldier haunts the entrance every August 24, Saint Bartholomew’s feast day. Others say dead monks glide through the aisles, and nuns drift through columns like they’re late for an afterlife confession. One poor soul even claimed to hear Latin hymns—no choir, no explanation.

We didn’t see any of that. But we did see a girl in full quinceañera regalia mid-photo shoot.

There she was—draped in an ocean of blue satin and tulle, flanked by photographers and family, posing like a royal in front of the altar. As she rotated through choreographed expressions of joy and reverence, a small army of aunties made way for the next lighting adjustment. We tried not to stare. We failed. It was too cool.

Somewhere behind her, 23 feet of wooden Jesus looked on with the flat-eyed solemnity of someone who’s seen it all—literally. Cristo de la Unidad, they call him. Christ of Unity. Seven meters tall, bare wood, arms outstretched like he’s trying to settle a centuries-old argument between the Spanish and the Maya. Good luck with that one.

The whole cathedral is subdued to the point of silence as if it were designed less for glory than for endurance. There's the portrait of Tutul Xiu, the Maya chief of Maní, paying homage to Francisco de Montejo, the Spanish conquistador. The painting marks their uneasy alliance—a political maneuver that helped Montejo conquer Yucatán after Xiu had already defeated their mutual enemy, the Cocomes, in one of the great regional flameouts of the late Maya era. It seems the “enemy of my enemy" can end up in a cathedral mural. There's also the royal coat of arms on the front of the building, which has gone through more branding updates than most tech startups—Spanish lions, Mexican eagles, and a brief cement phase where it was all just…smoothed over.

And then there’s the echo. Not just the sound of footsteps or whispered prayers. A deep, eerie echo that bounces once, maybe twice, and then disappears like it knows it’s not supposed to be there. We figured it was just acoustics. Unless it was that flayed guy doing skinless laps.

We left quietly. La quinceañera was just outside, mid-pose, making sure the photos showed that she was, in fact, in front of the most important church in the city. Good luck to her, I say.

We never did get back to the cathedral, but it was enough. The photos are a little blurry, the shadows a little too long—but they tell a truer story than any wide-angle shot in the morning sun.

That’s the strange thing about cathedrals—you think they’re all stone and saints, but really, they’re memory machines.

And you don’t leave something in this one. It leaves something in you.

Write a comment