You can’t miss the Monumento a la Patria (Monument to the Motherland) at the northern end of what is arguably Mérida’s most famous street, the Paseo de Montejo. It’s a massive, ring-shaped block of history carved in stone and dropped right in the middle of the roundabout where Paseo de Montejo intersects Highway 261.

Back in the ‘40s, Mérida was a city caught between two identities. The henequen boom that had flooded the city with money for two generations was long over, but the scars it left were still visible. The city was modernizing, but it was also trying to hang onto its history. The grandeur of Paseo de Montejo was starting to feel more like a memory than a promise.

So the city decided to build a monument dedicated to the Mexican flag. Something solid, something patriotic, something respectable. Something that said, “We’re proud to be Mexican” and “Things are bound to get better again.” Something with heft that showcased the city’s national pride, maybe some eagles and some dramatic stonework. Done.

But then they hired Rómulo Rozo.

Rozo wasn’t from Mérida, or even Mexico, but he might as well have been. Colombian by birth, he’d been living in Mexico since the 1930s, carving out a reputation (see what I did there? Carving. Get it?) as someone who knew how to tap into indigenous culture in a way that felt authentic, not touristy. His work blended reverence and audacity. And the city definitely wanted something that felt important.

He took the massive-flag concept and expanded it to include the entire story of Mexico. From ancient civilizations to colonial conquest to revolutions and reform. And not with plaques or statues that people walk past without seeing but carved into the stone. He wanted it big and bold and impossible to ignore.

Which is how the city’s flag monument turned into the epic we have today. The project began in 1945, and Rozo didn’t just design it—he lived it. He worked closely with locals—architect Manuel Amábilis Domínguez and master builder Víctor Nazario Ojeda. It took 11 years. Not because they were slow, but because Rozo insisted that every single figure—more than 300 of them—be hand-carved. No shortcuts. Every face, every animal, every historical scene was carved directly into locally quarried volcanic tuff. You might think he was being obsessive, but walk around the monument today and you’ll see why it took as long as it did.

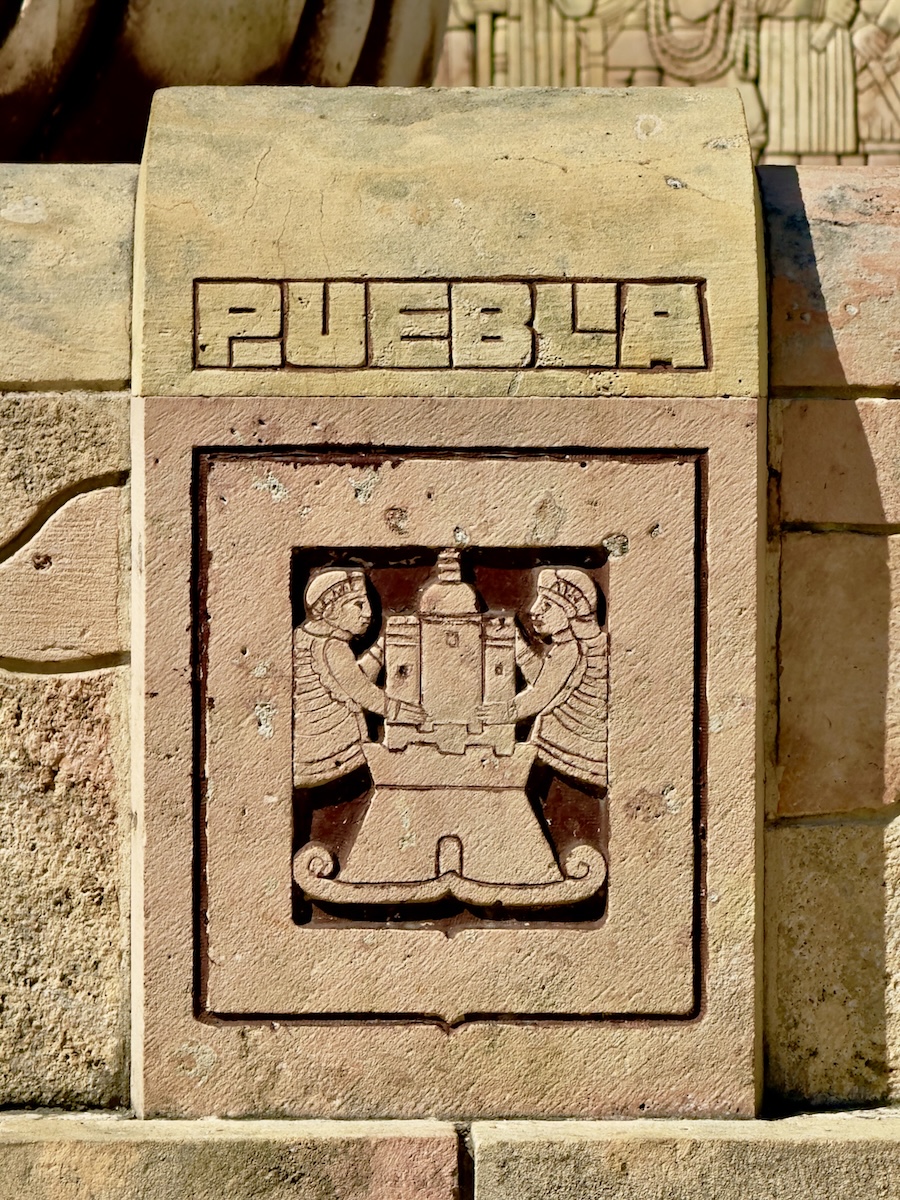

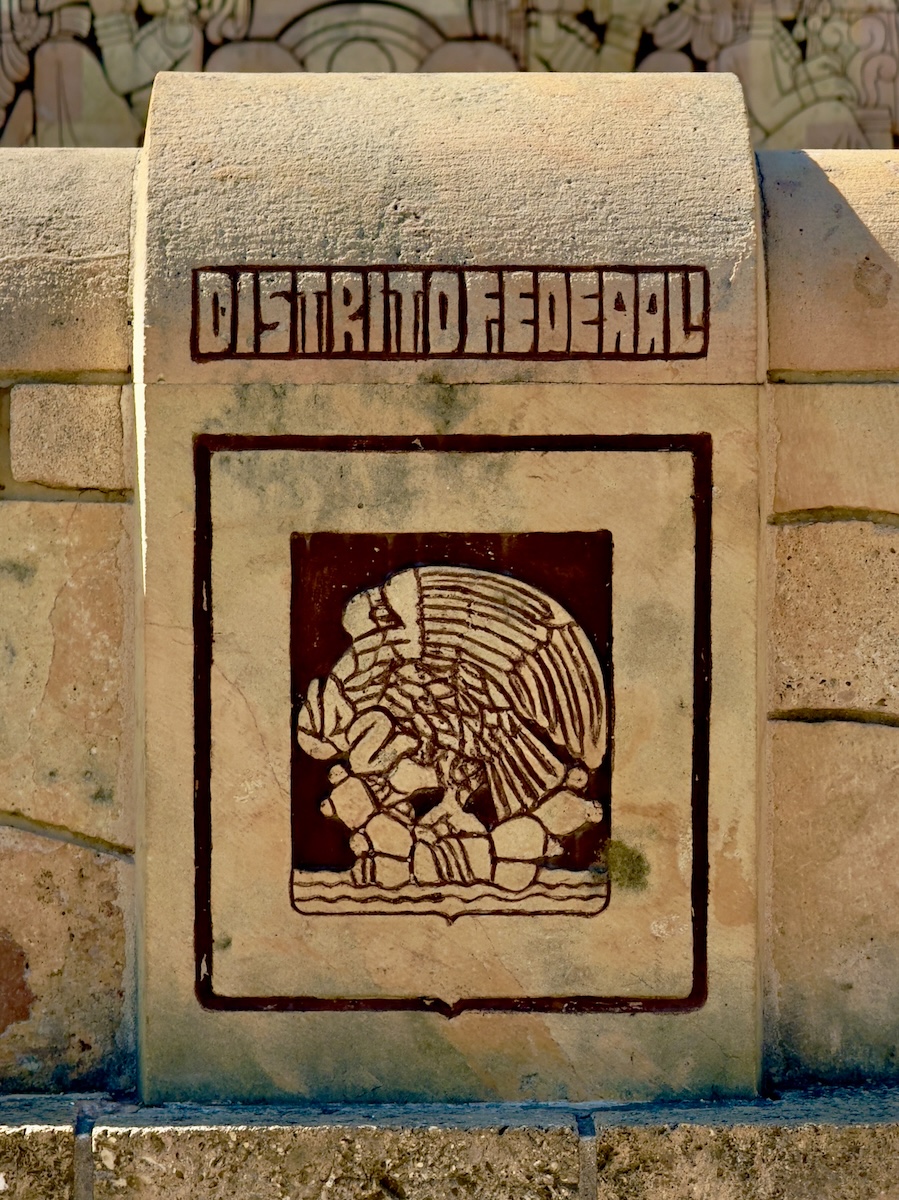

The monument tells a long, complicated story. It starts with the founding of Tenochtitlán (where Mexico City now stands), nods to the Maya with carvings of jaguars and chacmools, and moves through the centuries—Spanish conquest, independence, revolution, reform. There are depictions of major figures like Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morelos, and revolutionary leaders like Zapata and Villa. The central figure is a mestizo woman wearing Mayan-style jewelry and a coat of feathered serpents. Flanking her are two hybrid bird-fish creatures that symbolize sovereignty over sea and sky. Below the coat of arms of Mérida sits a Mayan hut that contains the votive flame of the Mexican homeland, surrounded by various Mayan jaguars, chac mools, snails, rattlesnakes, and other Yucatecan flora and fauna. Surrounding it all is an allegory of offerings—12 deities holding the fruits of the earth and the arts, a tribute to pre-Hispanic creativity and labor.

There’s no real order to the historical carvings that wind around the monument. The stories overlap and blend. Some figures loom large, while others are almost hidden, waiting to be noticed. It’s chaotic but deliberate—maybe the only way to represent a country like Mexico whose history is anything but straightforward.

The design itself is a strange but successful marriage of Art Deco and neo-Maya design. Clean lines and sharp angles mix with intricate carvings that feel ancient and rooted. It totally works, mirroring Mexico’s layered history. It’s actually amazing, serious without being preachy. Rozo didn’t treat Mayan culture as an aesthetic to be borrowed, but as something living, important, and real.

The monument is a huge, complicated statement that feels like it’s holding its breath, waiting for someone to really pay attention. And you should. Because even if you don’t know every figure or moment etched into the stone, the monument doesn’t let you walk past without feeling something.

Which is exactly what it was meant to do.

Write a comment