The Palacio Cantón is one of the flashiest buildings on Mérida’s grand boulevard, Paseo de Montejo. A bright yellow Beaux-Arts mansion with a spiral staircase and Italian marble, it looks like the kind of place where you’d have been shot for scuffing the floors. Today, you just buy a ticket and head inside. But still…don’t scuff the floors.

The mansion now houses the Museo Regional de Antropología de Yucatán—one of the city’s best museums and, depending on how you feel about historical irony, one of its most satisfying.

The house was built in the early 1900s by General Francisco Cantón Rosado, a conservative politician and military man who spent much of his life fighting the Maya in a long and brutal conflict known as the Caste War. That war, which began in 1847, was a massive indigenous uprising against the Spanish and Spanish-descended elites who ruled the Yucatán. It lasted more than 50 years (!). You'd be forgiven for not knowing that, though—Mexico doesn't exactly teach it in depth, and it's not even a footnote in U.S. history classes. Cantón joined the fighting as a teenager, made his name as a commander on the front lines, and rode that résumé into a governorship, a railway fortune, and finally into this magnificent mansion.

So yes, there’s something darkly amusing about the fact that his old house is now dedicated to preserving and celebrating the very culture he spent a lifetime trying to eradicate.

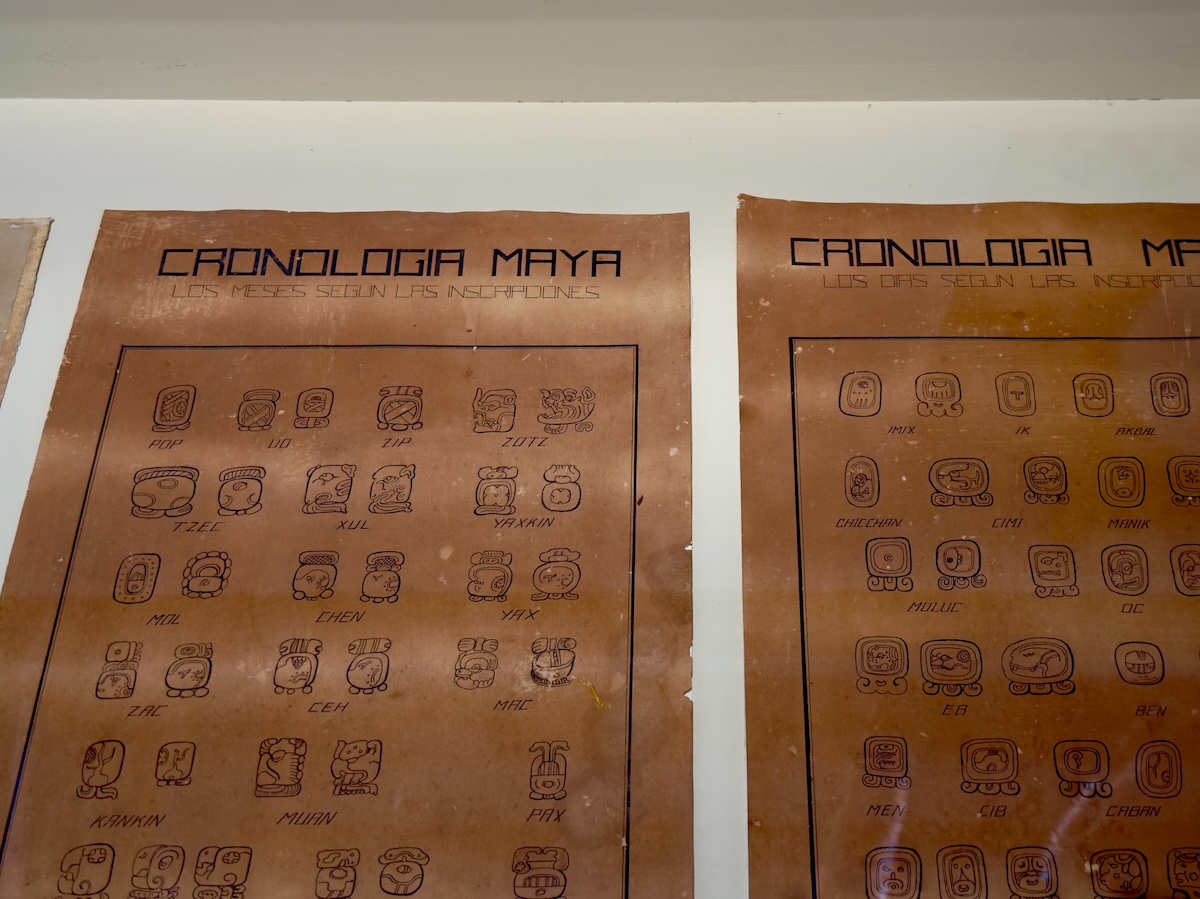

And it does a good job of it. Unlike the newer, flashier Gran Museo del Mundo Maya on the edge of town—designed for crowds, field trips, and the occasional light show—Palacio Cantón is smaller, quieter, more selective. You don’t wander through it so much as pay attention. Each object— a carved limestone stela with faint glyphs, a jaguar-toothed ceremonial mask, a textile dyed in earthy reds and worn to threads—earns its place. The first floor is dedicated to pre-Hispanic Maya society, while the second floor rotates temporary exhibitions.

The building itself adds another layer. Even without the museum, you’d come just to see it. The architecture is exactly what you’d expect from someone who made millions laying train tracks for henequén exports and had zero interest in subtlety. Doric columns, Italian marble, frescoes over the doors—it's almost makes you think, "This seems a bit much.” But then it was built during the Porfirio Díaz presidency, when “a bit much” was the general aesthetic.

But it's also beautiful, in that careful, imported way. And it creates a delicious tension—an opulent home, once a monument to Yucatán’s colonial wealth, now filled with relics of the civilization that wealth helped dismantle. You almost expect Cantón himself to come stomping down the marble staircase demanding to know why there’s a gallery full of jaguar gods in his drawing room.

Cantón died here in 1917, but the family clung to the house for another 15 years, renting out the first floor and selling off furniture piece by piece. Eventually, the state took it over, and like most big empty buildings, it became a bit of everything—a school, an arts academy, a governor’s residence. The museum appeared in the 1950s—first in the basement, like an afterthought—then quietly crept upstairs. Somewhere along the way, the past caught up with the house. Or maybe just evened the score.

There are other places to learn about the Maya in Yucatán, but few come with a setting this conflicted. The palace doesn’t try to resolve the contrast between its origin and its present. It just lets you walk through it—one tiled hall, one carved stone, one quiet reckoning at a time.

Write a comment