The Museo Amparo opens with a hall built for ceremony—high ceilings, clean lines, and an echo that makes you self-conscious about your squeaky soles. Light pools on polished stone. The temperature drops fast, like the building knows you need a second to recalibrate. There's no visual noise, frenzied signage, or museum shop detour before the first room. Just space. Measured, confident, and disarmingly quiet.

The museum opened in 1991, founded by Manuel Espinosa Yglesias in memory of his wife, Amparo Rugarcía de Espinosa, whose family once lived in part of the building. Dedicated to preserving, researching, and showcasing Mexican art from pre-Hispanic times to the present day, it occupies two historic structures—a colonial-era hospital and an 18th-century residence—which have been carefully renovated and stitched together with just enough modern design to keep it from sliding into reverence. The result isn’t a shrine or a reconstruction—it’s more elastic, more self-aware, a place where history isn’t frozen but still makes itself known.

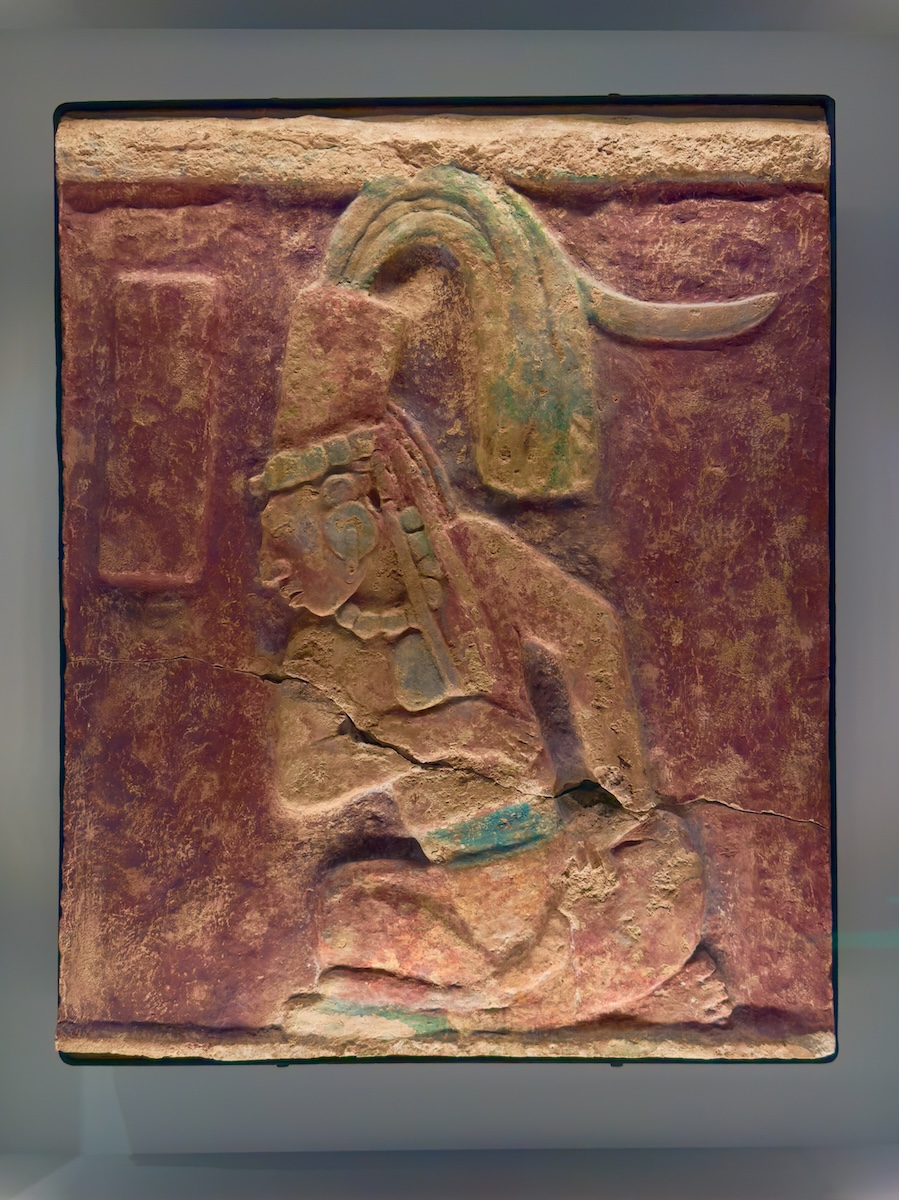

We began our own visit in the Pre-Hispanic galleries, deep in the heart of the building, where the concrete is bare and the artifacts are blunt. There’s no “gentle ramp up” here—you’re immediately surrounded by jaguar gods, burial urns, and abstract ceramic figures with almond eyes. Long glass cases provide an even longer view of Mexican antiquity.

There’s a deliberate contrast at work here with centuries-old items presented in an ultra-modern shell. Concrete meets volcanic stone. Spotlights pierce the stillness. Clay figurines and vessels so old they make your existence on this earth feel like a blip. Objects here are simply labeled—date, material, region—and left to confront you without irrelevant commentary.

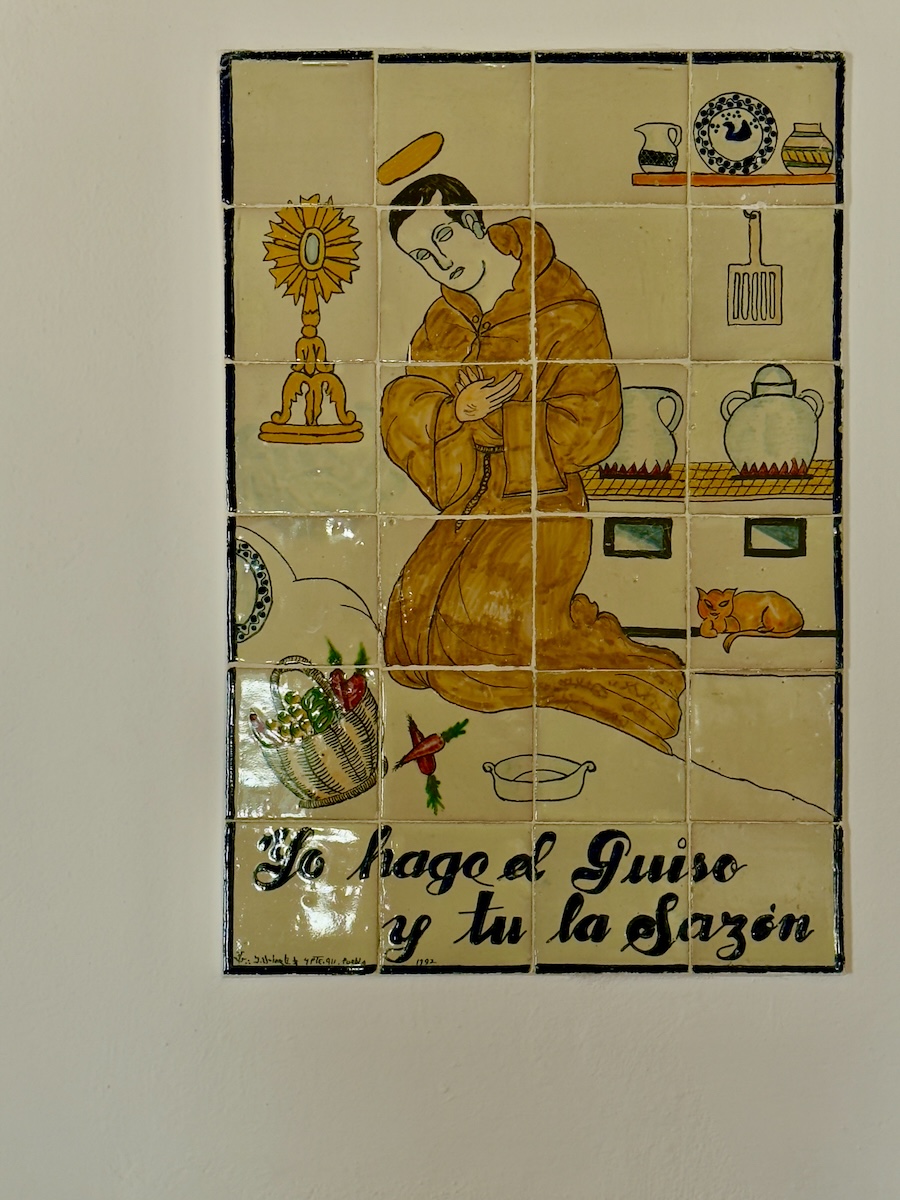

The contrast sharpens as you climb the stairs—original stone, the kind that creak even when they don’t—and the museum shifts gears, this time into full domestic mode. The layout changes. The lighting warms. You’re not in a gallery anymore; you’re in the Espinosa family home, which once housed generations of lawyers, doctors, and city leaders. Now it’s home to the museum’s Viceregal and 19th-century collections, though calling it that feels too clinical. It’s more like domestic archaeology. The rooms seem dressed for company, every surface carved, upholstered, embroidered, or polished. Saints line the walls with glossy wooden eyes. Silverware glints from locked sideboards.

And it works. Mostly because the family never fully left. Their names are still on plaques, and their stethoscopes and legal certificates are in glass cases downstairs. The whole place walks the line between private memory and national exhibit, and you feel it when you pass from room to room—almost like you’re trespassing.

There’s a careful kind of storytelling here. You're not just looking at art from the colonial and early republican periods—you're seeing it in context. The silver, the textiles, the ivory carvings—they don't just belong to an era, they belonged to people, and in this case, people who left their names and furniture behind. It's the part of the museum that feels most intimate and loaded. The wealth, the religious iconography, the sheer effort that went into displaying status—it's all laid out quietly and without apology. Tiled from floor to ceiling in Talavera, the kitchen steals the show. There's a stove the size of a Fiat and a water basin worn into shape by decades of scrubbing. It’s the room that tells you the most without trying—a blend of utility and display, faith and firewood.

Eventually, we reached the rooftop café, more out of curiosity than hunger. The café is a smart addition—all glass railings, minimalist furniture, and singular views of Puebla’s rooftops stretching into the haze. It is a bit trendy, but it also gives you a moment to sit with everything. The vibe up here is distinctly 21st-century, but not in a way that tries to erase what came before.

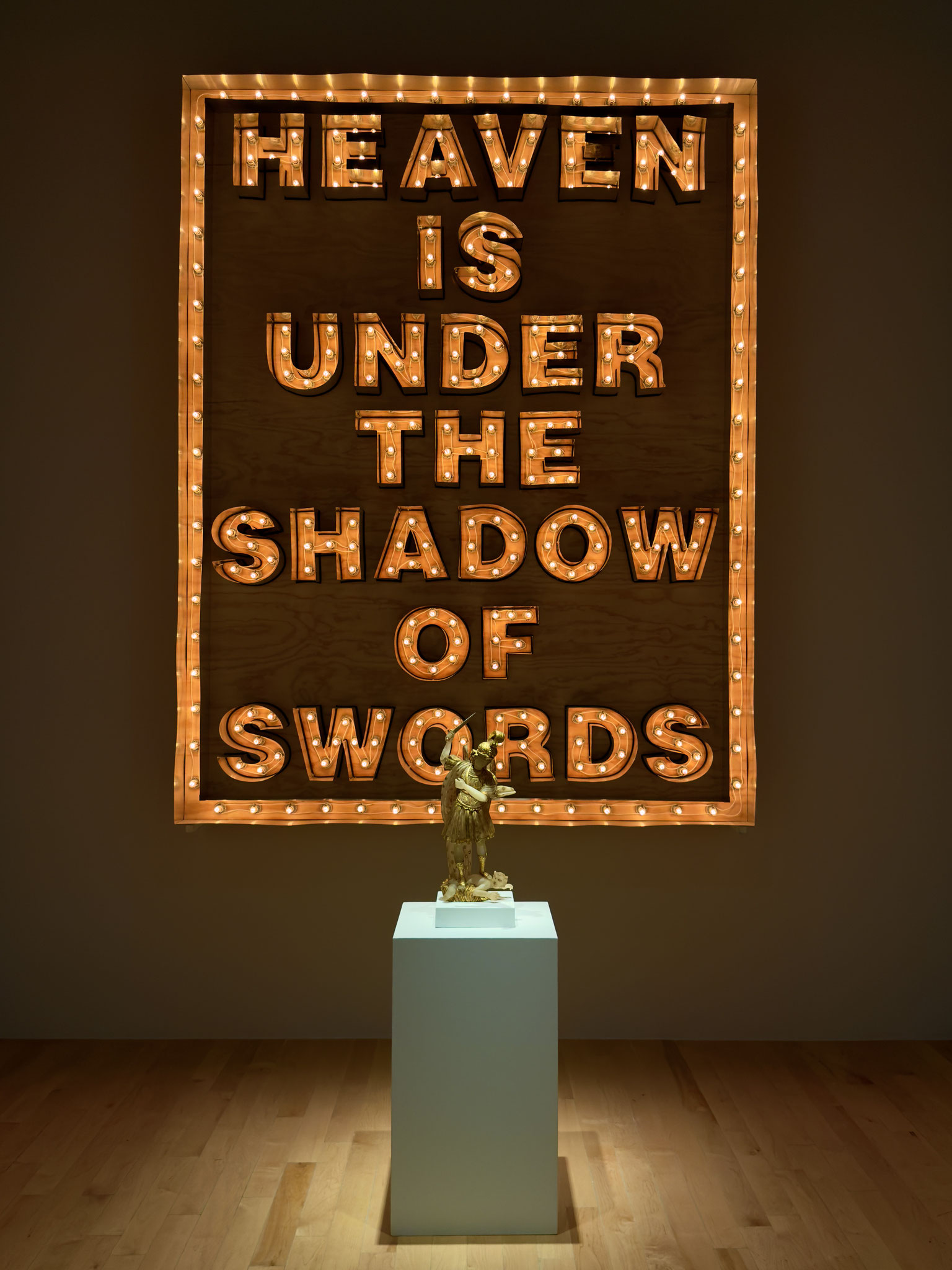

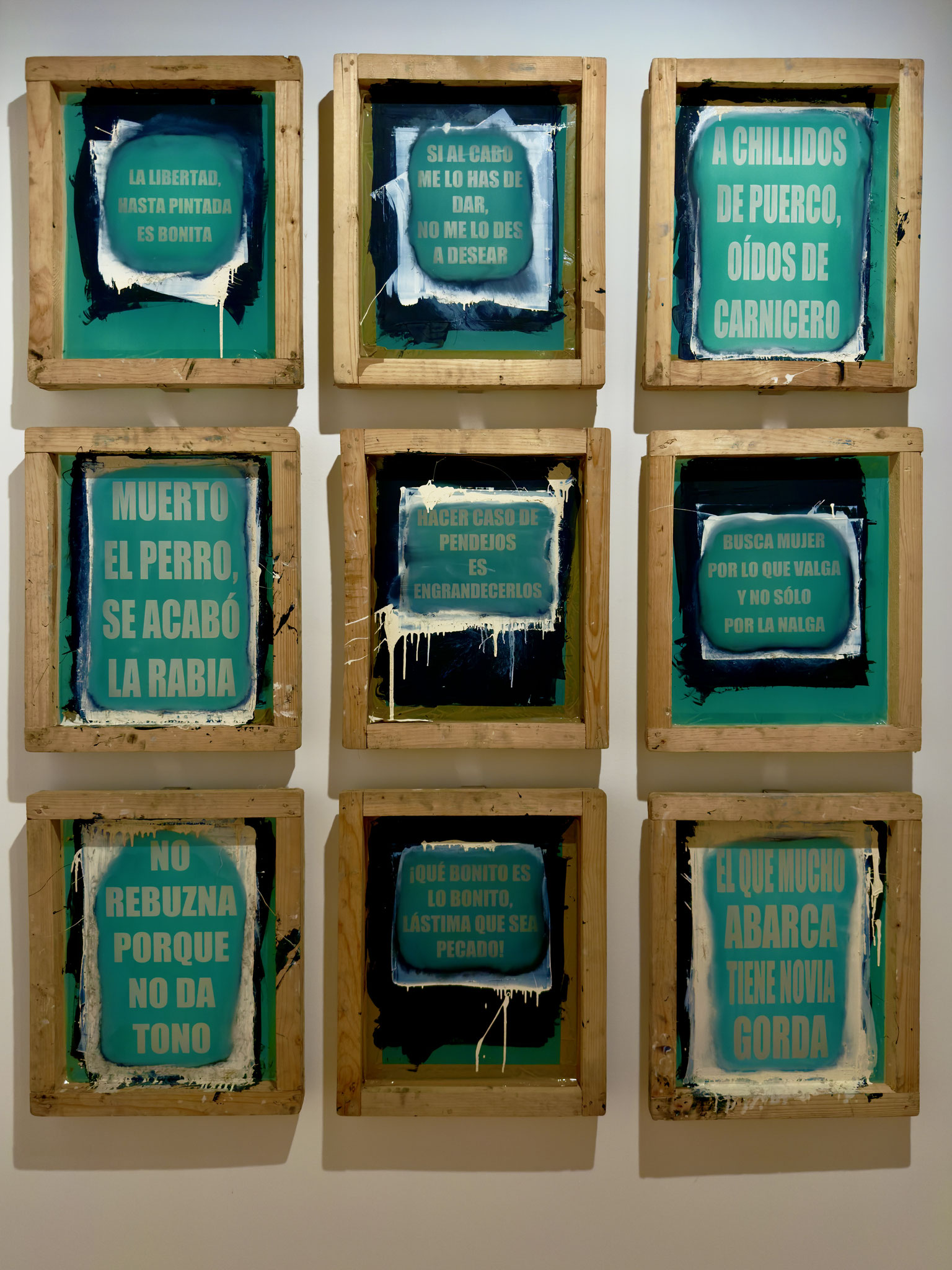

The final section contained the 19th- and 20th-century galleries. No more bedrooms. No more saints. Just walls and the work of a country trying to paint its way into modernity. The rooms are plainer and brighter. The art gets bolder, less reverent, and more interested in people with opinions and problems. After the historical depth of the Pre-Hispanic artifacts and the intimate weight of the Viceregal house, these rooms feel like an exhalation of relief. There’s space again, but now you’ve earned it. Even the silence feels different. Less sacred, more alert.

And that’s how the Museo Amparo holds itself together. It doesn’t just arrange objects by era—it layers them into the structure of the building. Ancient clay, colonial wood, modern glass—all in conversation, all with something to say. The past here isn’t trapped in glass. It’s walking alongside you, waiting for you to catch up. It’s not subtle, but it’s not showy either. Just like Puebla itself.

Write a comment