“Una persona, por favor,” I said confidently, like someone who had totally not practiced that exact phrase eighteen times in the mirror earlier that morning.

Ticket Lady (Spanish): We don’t take credit cards.

Me (Spanish): Okay, I have cash.

Ticket Lady (Spanish): Do you need a guide?

Me (Spanish): Yes, I’ve got the cash.

Ticket Lady (Spanish): No, do you want a tour guide? We don’t have one that speaks English right now, but she will be here for the next tour.

Me (Italian): I’m sorry, I don’t understand.

Ticket Lady (Spanish): What?

Me (Hungarian): Can you speak more slowly?

Ticket Lady (Spanish): Are you okay? You’re speaking gibberish.

Me (beginning to panic): …ummmm…

Ticket Lady (Spanish): Can you feel your left arm? Is the light fading?

This is how I began my solo visit to the Panteón de Belén, Guadalajara's legendary cemetery, unsure if I was going to see ghosts or become one.

The Panteón was built in 1848 during a cholera epidemic, which seems a little on the nose. Guadalajara needed somewhere fancy to bury the city’s political, scientific, and religious elite—people whose tombs came with columns, not just crosses. This neoclassical beauty, designed by Manuel Gómez Ibarra, who was also responsible for the cathedral in town, was the answer. The cemetery was active for just 50 years, until new laws and lack of space brought burials to a stop.

The Panteón was originally part of the sprawling Hospital de Belén complex. And I do mean sprawling—the hospital still exists, and its buildings now wrap around three sides of the cemetery. Which is a choice, I guess. Nothing illustrates the circle of life quite like a maternity ward on one side of a wall and mausoleums on the other.

The cemetery is small but immaculately planned, with a symmetrical layout centered on a grand circular mausoleum that sits over a small chapel that is home to the remains of men considered important to the development of Guadalajara, including Gómez Ibarra himself. The towering mausoleum at the center is topped by a striking 120-foot-tall, tiled pyramid with clear Egyptian influences made even more dramatic by four statues of wailing women perched at its corners like grief-stricken gargoyles.

Straight paths radiate outward from the central tower like a sunburst. Or a compass pointing ghostly apparitions to the afterlife. Spread across the grounds are tombs and monuments in a range of styles—from simple stone slabs to elaborate sculptures—all carved in pale Cantera stone and shaded by cypress trees.

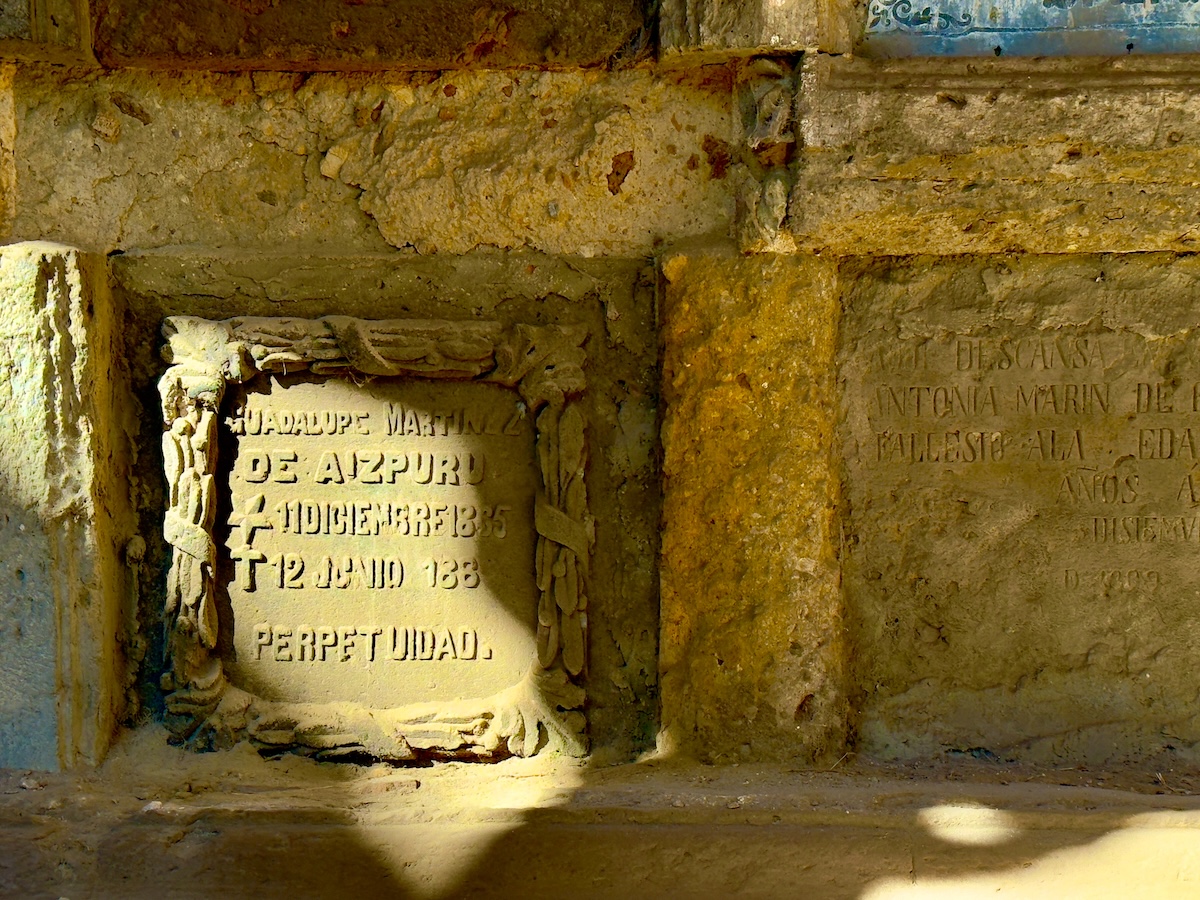

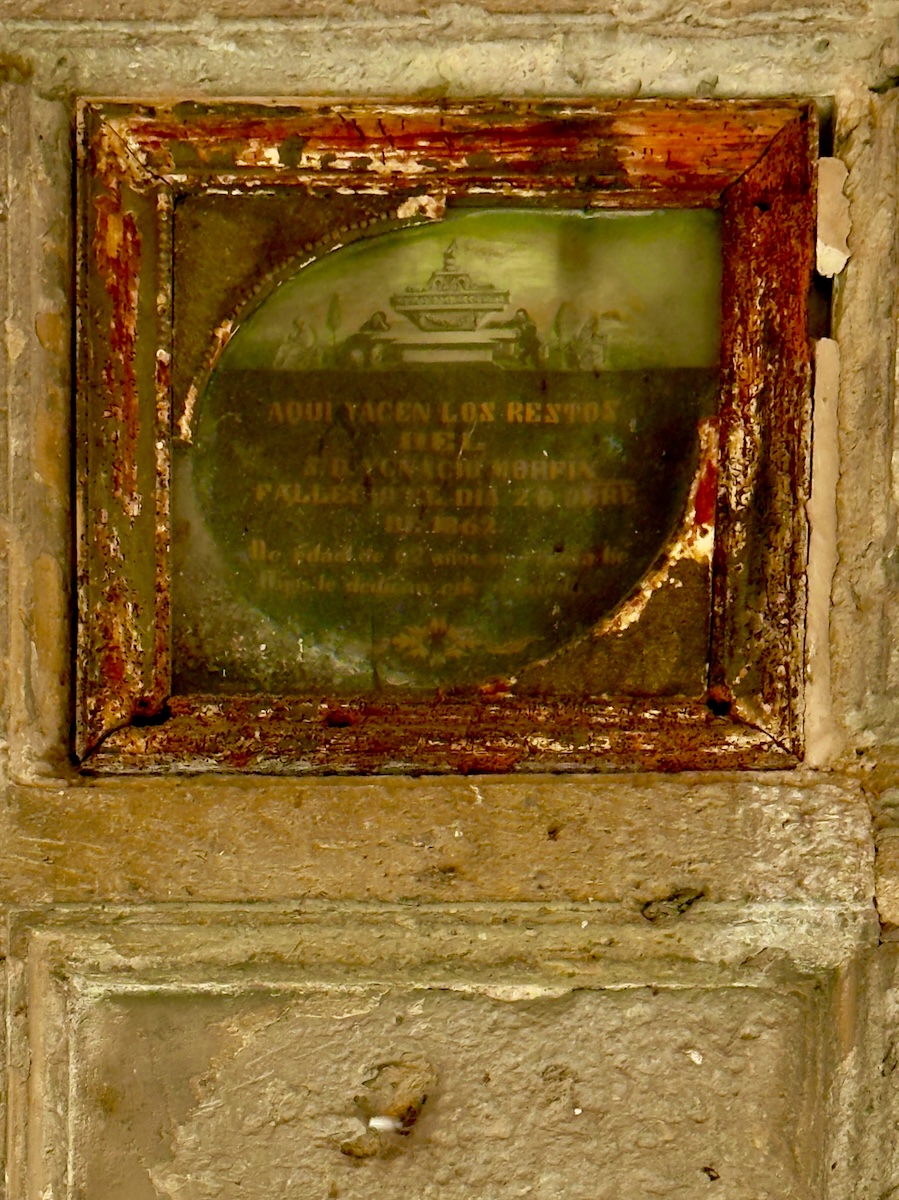

Flanking the space are two original colonnades—only half of the four originally planned—that frame the northern and western sides of the cemetery. Each arcade features 50 arches, with burial slots tucked between them. Rows of stone columns topped with classical Ionic capitals give the arcades an architectural grace that contrasts with the weathered slabs whose inscriptions are now more rumor than record.

There’s a beautiful calm in the place, even in this busy part of the city, that hovers between reverence and suspense. Some of the tombs are grand mausoleums with spires and Masonic symbols, others are small slabs with fading names and candle stubs. You don’t have to believe in ghosts to know that the people buried here were very serious about being remembered.

Picking my way through the dead cypress leaves and cracked tombstones, I found the massive, gnarled, and unsettlingly vigorous vampire tree (El Árbol del Vampiro). “Vampire tree, you say?” Yep. Apparently, a pleasant-seeming man named Jorge moved to town in the mid-1800s. Polite. Well-dressed. Easily sunburned. Shortly thereafter, livestock started turning up dead. Not mangled. Not butchered. Just… empty. Of blood. And marked by two tiny punctures. You know, the type of thing you hardly notice until children start going missing.

People couldn’t bolt their doors fast enough. Parents prayed. Neighbors eyed each other with suspicion. Eventually, a well-meaning mob with pitchforks decided to go vampire hunting. Jorge met his end, deserved or otherwise, with a wooden stake through his heart. Being good Catholics, of course, they buried him in the local cemetery (this one!), though they did top his grave with a massive stone slab to prevent his escape.

Jorge never did show up, but that pesky wooden stake sprouted, and a tree grew from it, eventually punching through the stone, twisting up and out like something from a Guillermo del Toro movie. According to the locals, the trunk bleeds when cut. And if the stone slab ever breaks completely…dramatic pause…the vampire will rise again and, presumably, be very annoyed.

The vampire tree is fenced off these days—probably less to do with the danger of setting a vampire loose and more to keep people from snapping branches off willy-nilly to test the blood-sap theory. But I can tell you the tree is very real, as is the crack in the tomb. And it does look a little like something is trying to escape.

As I looped around the outer paths, I passed two more infamous graves—the tomb of Nachito, a child supposedly too scared of the dark stay in his grave, and the unmarked Monk’s Grave that is rumored to contain a cursed clergyman. I didn’t linger. I wasn’t here for the ghost stories, I told myself. Just the architecture. The design. The cultural preservation. But I did pick up the pace.

I wandered around for about an hour, by the end of which I felt a mix of awe, dread, and mild sunstroke. The Panteón is stunning—full of dramatic carvings and dramatic-er backstories. It’s also oddly tender. These aren’t just gravestones, they’re fragments of actual people buried beneath layers of myth and moss.

Eventually, I made my way back to the entrance gate. Ticket Lady looked up from her phone.

“¿Todo bien?” she asked.

“Sí,” I nodded.

“¿Puedes sentir tu brazo? ¿Mueves los dedos?”

I gave her a thumbs up.

“Perfecto,” she smiled.

Write a comment